Home --> Christina Holt's Story --> Christina Holt's Story: Newspaper Articles --> 2001 - 2006

Christina's Story

- Newspaper Articles

The following links take you to various articles in Christina's story

as it appeared in the South Florida media.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE INFORMATION ON THIS SITE BEFORE ASKING.

Thank you!

|

|

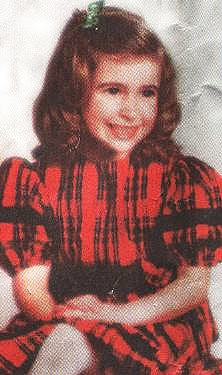

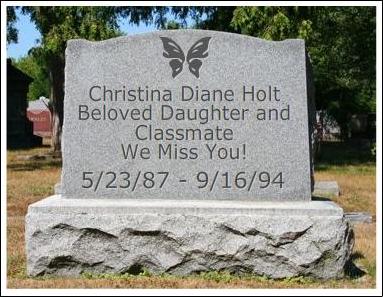

In Loving Memory Of May 23, 1987 - September 16, 1994 "Beautiful Child who has found love from the angels...RIP..." |

(Not her actual headstone) |

These

pages contain all of the articles from the Palm Beach Post and The

Sun-Sentinel throughout the years. |

|

Mom Says From Prison:

'I've Grown Up Now' (5/22/01)

Boy's Slaying Stirred a Nation (7/22/01)

Heck For Live-In Peril (1/20/02)

In Court (1/31/02)

Mom Appeals Conviction (2/23/02)

Stop Protecting The System That Fails State Children (5/9/02)

Pulling Dark Secrets From The Dead (7/4/04)

Stories Of Abuse, Children's Names Will Echo Forever in

A Community (5/19/05)

Noted Lawyer Etched Reputation in Creativity, Aiding Unpopular

-- Ellis Rubin, 1925-2006 (12/13/06)

MOM SAYS FROM PRISON:`I'VE

GROWN UP NOW'

Sun-Sentinel

May 22, 2001

Author: Marian Dozier Staff Writer

Every day of her narrow, monitored existence in a maximum-security prison,

Pauline Zile says she contemplates a hundred "what ifs, could haves,

should haves," knowing that she did nothing to stop her husband

from killing her first-born child. Worse, she helped him cover it up.

In the more than six years since

7-year-old Christina Holt was killed, Pauline Zile had not talked --

until now.

In an hourlong interview last week from Broward Correctional Institution

in Pembroke Pines, where she's serving a life sentence, Zile talked

about the "pain that's always there," about losing her three

other children to adoption and about still loving John Zile but not

being "in love with him."

She also talked about herself: I was a follower, she said, a scared little girl terrified of an abusive spouse.

"I was a young, dumb, naive child who listened to what she was told and did whatever I had to do to survive," said Zile, now 30. "I am more my own person now than I think I've ever been. ... I've grown up now. I've seen what went wrong. I'm not afraid to speak my mind or my opinions. I don't allow others to control me anymore.

"I think I've really grown up in my time here."

Christina died Sept. 16, 1994, after her stepfather, John Zile, suffocated her by holding his hand over her mouth while beating her for defecating on the floor of their Singer Island apartment.

That's not what the Ziles told police and others. Teary-eyed, the couple stood before TV cameras and described how someone abducted Christina during a family shopping trip to the Swap Shop, a Fort Lauderdale flea market.

Their performance helped make Christina's disappearance national news -- even as Pauline knew that John Zile had killed the girl, stuffed her body in a closet for four days, then buried her behind a Kmart store in Tequesta. He pawned her bicycle and some videotapes to buy a tarp and shovel used to dispose of her body.

It wasn't until late October 1994 -- four days after a bungled double-suicide attempt in an orange grove -- that Pauline Zile came clean, implicating her husband in the killing. Both are now serving sentences. John Zile is under protective custody at Tamoka Correctional Institution near Daytona Beach.

In an exclusive interview with WPBF-Ch. 25 reporter Tim Malloy, scheduled for broadcast at 11 tonight, Zile said she doesn't think she's guilty of murder. Rather, she blames her conviction on inadequate representation by her prior attorneys, Ellis and Guy Rubin of Miami.

She has filed a motion in Palm Beach Circuit Court to have her conviction overturned. She's representing herself but is getting legal advice from West Palm Beach lawyer Robert Gershman, who at one time was appointed to represent her.

The state attorney's appellate office has until Friday to respond to her motion, Gershman said.

"I help her, but I'm not the attorney of record on that case," Gershman said. "I hope to be again because she deserves a new trial. [The Rubins] did nothing. The work product in preparation for trial was not adequate, especially given the gravity of the case."

In October 1999, the Florida Supreme Court dismissed an earlier appeal Zile filed, based on her belief that her statement to police implicating her husband was used against her.

"There's regret, not necessarily guilt," she said on the videotape. "... I don't deserve to be here. I know I did wrong, but I don't think it's right for me to sit here for the rest of my life for a crime I didn't commit. ... I'm guilty of the omission, you know, and for lying about it."

But why didn't you call police? Malloy asked her. There was no phone in the apartment, Zile answered. Plus, she said, when she asked John Zile if she should call 911, "he stated, `We wouldn't be here when you get back.' ... I was scared of leaving at all, of moving, of anything. I was in shock." She said she also was afraid he might kill the other children. And at the time, she was eight months pregnant and "scared witless," she said.

While she doesn't think John Zile suffocated Christina on purpose, she said she never went into the room to see. She watched John carry Christina out, take her to the bathroom, douse her with cold water in an attempt to revive her, but beyond that "I didn't want to know," she said. "All I know is I stayed out of that room and kept the children out of that room."

Those two children -- and a third Zile delivered in prison -- have been adopted. Zile doesn't know by whom but said their new parents keep her updated on their lives. The two boys, now in their early teens, are with one family, the younger child -- Zile wouldn't reveal its gender -- with another. Zile said she and her husband are listed in an adoption registry should the children one day want to meet them.

On camera, Zile looks older than her years, especially compared to the young, slight woman of seven years ago with glazed eyes and long, unkempt hair. She wears glasses, and her hair has been shorn.

She cries a lot and says she's sorry. Her faked TV persona was borne of shock, she said, and "maybe not quite believing [Christina's death] was actually true."

The tears, she said, "were real," and she realizes that the duped public "wanted me on John's lap in the electric chair, point blank, and I knew that, but they didn't know both sides of the story ...

"I didn't stop it [Christina's death], nor did I say anything about it. I wasn't thinking. I was doing what I was told."

By John, Malloy asks?

"Yes."

Marian Dozier can be reached at mdozier@sun-sentinel.com or 561-243-6643.

BOY'S SLAYING STIRRED A NATION

ADAM'S ABDUCTION AND MURDER IN 1981 RAISED PUBLIC AWARENESS AND PRODUCED

LEGISLATION TO HELP PROTECT OTHER YOUNGSTERS.

Sun-Sentinel

July 22, 2001

Author: Jonathon King STAFF WRITER

Twenty years ago, his name came over a loudspeaker at the Sears store

in Hollywood: "Adam Walsh, please come to customer service."

Who in the shopping aisles on

that July day in 1981 would have recognized the name of the lost 6-year-old?

Who in South Florida, or across the nation, would not at least turn

an ear to such an announcement today?

Two decades after Adam was abducted and his severed head was found in

a Vero Beach canal, his name rings synonymous with the missing children's

movement.

His father, John Walsh, is a national celebrity with his anti-crime TV show and his tireless work to change how America looks at and for missing children. The image of Adam's gap-toothed smile is stamped on child safety literature nationwide. His legacy has touched institutions from law enforcement to public architecture to business policy to Congress.

"Everyone remembers the story, and it doesn't matter what part of the country you're in," said Debbie Coller, a vice president with Boca Raton-based Sensormatic, a corporate sponsor of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. "What happened with Adam Walsh in South Florida 20 years ago created a cultural change across America."

On July 27, 1981, Adam's mother took him to the Hollywood Mall to do some shopping. They were in the Sears store, where several other kids had gathered in front of a video game in the toy department. Pac-Man was a new fascination.

Reve Walsh let Adam stay and watch while she shopped a few aisles away. When she returned, he and the other children were gone. She began calling his name. She approached other shoppers. She told a security guard. After more than half an hour, they made a fruitless "come to customer service" announcement to a 6-year-old.

"Cash registers kept ringing up sales. Clerks kept waiting on people as if nothing had happened," Reve described in John Walsh's book Tears of Rage. "I was trying to think of the words to make them see that something was really out of whack. That something was going on that just wasn't right. I couldn't just go up to the counter and say, `I have a missing child,' because in those days, there was no such thing."

Stores on alert

Almost twice a month in the summer of 2001, a "Code Adam" alert comes over the speaker system at the Wal-Mart store on West Sunrise Boulevard. The announcement, named after Adam Walsh, means a child has been reported missing in the store.

The employees know their roles. A brief description of the child is announced and they all stop their work to look. Some are immediately assigned to immediately watch all exits to make sure the child doesn't leave the store.

Within 10 minutes, if the child is not found or is seen with someone other than a parent or guardian, the local police department is called.

The Code Adam program, created in 1993 by Wal-Mart employees, is used at 15,000 stores across the country including Gap, Home Depot, Kmart and Office Max.

"The awareness that [the Walsh case] brought is immeasurable," says Sharon Weber, spokeswoman for Wal-Mart nationwide. "There's much more responsibility expected of corporations now than 20 years ago. People are much more concerned about missing children. Everyone is more vigilant."

In 2001, almost every retail outlet has surveillance cameras recording who comes and goes through its doors. Almost every large mall has computerized parking lot cameras, some so sophisticated they can pick up license plate numbers.

At Chuck E Cheese pizza playgrounds nationwide, parents and children get their hands stamped with matching numbers when they arrive and are checked when they leave to make sure the right child leaves with the right adult.

Architects design school buildings with single points of entry to help safeguard children and to keep strangers off the premises. On field trips, children wear color-coded T-shirts. Fingerprinting programs for youngsters and even DNA samplings are common. Movie celebrity Jamie Lee Curtis is the spokeswoman for a Ford Motor Co. campaign to distribute child identification kits to keep kids safe.

The heightened awareness follows two decades of missing children images on billboards, milk cartons, shopping bags and advertising fliers. After the Adam Walsh case, entrepreneurs even made a profit selling leash-like child restraints to a nervous public.

Yet the raw numbers refuse to diminish. In 2000, the FBI estimates 750,000 juveniles were reported missing. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children estimates that 3,200 to 4,600 of those were abductions by strangers.

"There have been tremendous reactive changes. But the behaviors of people haven't changed," says social scientist Martin L. Forst, author of Missing Children: Rhetoric and Reality.

"The majority of missing children are still runaways and parental abductions. But the fear that parents have that their child might be kidnapped shouldn't be diminished. The true change is that law enforcement is now much more prepared to act when it does happen."

Changing the law

Two hours after Adam Walsh disappeared, police were called. His mother and grandmother had swept the mall in a growing panic. John Walsh had arrived and was trying to work with the uniformed officers, whose headquarters were only a parking lot away, across Hollywood Boulevard.

Other than a short, local "be on the lookout" radio dispatch, little was done.

"There was apparently nothing in the book, no page in the manual, for what to do in this emergency. What to do if a little boy went missing," Walsh wrote in his book.

Twenty years later, there are more than a few pagesin the manual. Every large police department in the country has a missing persons unit and many have specific protocols for reports of missing children.

"An officer is going to respond immediately when you hear that a child is missing and they're going to start prioritizing right away," says Vickie Smith, a missing persons investigator for the past 12 years with the Palm Beach County Sheriff's Office. "Twenty years ago, I don't think they had that kind of urgency."

In 1981, only the officers in Hollywood would have heard Adam's "be on the lookout" broadcast. For the first several hours, only the people his mother showed Adam's picture to knew what he looked like. It took a week for the FBI to become actively involved.

In 2001, all that has changed.

"The difference is night and day," says Nancy McBride, director of prevention education for the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children in Alexandria, Va. "Today, within minutes, we can alert every police department up and down the road, coast to coast, and even internationally.

"Back then, we had to get a photo of the child, take it to a friendly printer and stand there waiting for them. Then we'd hand them out to volunteers and airline pilots and helpful travelers to spread them out.

"Today we scan the photo, e-mail it to the National Center and they burst-fax it to every police department, hospital, media outlet and pediatric office in as large an area as they think can be helpful."

Since its creation in 1984, the National Center has helped train 167,000 police officers to work missing children cases. The center has helped recover 57,000 children, McBride said. The recovery rate is now 93 percent, up from 62 percent in 1990.

After his son's death, John Walsh lobbied Congress to pass the Missing Children Act, which in 1982 mandated the creation of a national clearinghouse of computerized information to aid parents of missing children. It also ordered that the FBI's National Crime Information Computer be used and that local FBI offices assist parents.

In 1984, Walsh helped pass the Missing Children's Assistance Act, providing money for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and creating a toll-free hotline.

Walsh became a consultant for the Justice Department and pushed to get pictures of missing children on milk cartons, grocery bags and direct mail advertisements.

In 1988, the Adam Walsh Child Resource Center -- originally started by Reve Walsh in an abandoned police station in Pembroke Pines -- opened national headquarters in West Palm Beach. Two years later, it merged with the National Center.

"Suddenly, we jumped from a Broward County grassroots movement to nationwide," recalls McBride, who started working with Reve Walsh in the tiny Pembroke Pines office. "There are just so many changes since then, in law enforcement, in the media's reaction, in the public's awareness, in the technology. I'm not sure how you could measure it."

Would all those changes have made a difference 20 years ago, when a gap-toothed 6-year-old was snatched from a store, only his severed head found, and his killer still unknown?

Though she acknowledges that the percentage of abductions by strangers has not changed much in two decades, McBride answers the question without hesitation:

"I would hope that it would have made a difference. But I also know that as long as there are those people out there intent on hurting children, it will happen."

The danger remains

A 20-year list of abducted children still grew in South Florida after Adam's death.

Staci Jazvac, 11, a Lauderdale Lakes sixth-grader, was abducted on Jan. 30, 1986, and found dead in a field in Coral Springs 15 days later.

Michael Rivera is on Florida's Death Row for her killing.

Julie Magliulo was 3 when she disappeared in 1987. Almost a year later, her skeleton was found in a remote area near State Road 84 and U.S. 27. Her killer has not been found.

Amanda Dougherty, 5, was abducted from her North Lauderdale home in 1994. Her body was later found in a Palm Beach County canal. Her killer has not been found.

Jimmy Ryce, 9, was abducted, raped and dismembered in 1995 after getting off a school bus near his family's home in southwest Miami-Dade County. His killer, Juan Carlos Chavez, is on Death Row.

Each horrific case fosters some kind of change, whether it is one more parent becoming more wary, an entire police department rewriting a training manual, or a legislature adopting new laws.

After the abduction and murder of Jimmy Ryce, Florida legislators passed a bill that bears his name and requires police to notify residents when sexual predators move into their neighborhoods.

"We are now light years ahead of where we were," Jimmy's father, Don Ryce, said at the second annual "Missing Children's Day" last September.

"Now pictures of missing kids can be posted in public buildings. We have the Jimmy Ryce Act that, for the worst of these people, we can simply commit them and require them to get treatment. We have all sorts of [search] techniques that were unavailable then. But we're still a long way off from where we need to be."

Official attitudes may have made the largest leap since 1981.

"It wasn't an easy fight to get legislators to pay attention to children's issues back then. Now they all do," said Florida's former U.S. Sen. Paula Hawkins, a longtime children's advocate who teamed up with John Walsh to push through the Missing Children Act in 1982. "Too many senators thought it was interfering in family business. But after Adam disappeared, there was such a media storm they couldn't ignore it."

Hawkins credits John Walsh with bringing the issue to the public with his appearances on news programs, his collaboration on the 1983 television movie Adam and his willingness to bring his personal pain into a public spotlight.

For 20 years, the warnings he and his wife sent out have shifted a society off its safe complacency.

"Everybody has a different level of anxiety and level of freedom they'll give their child. That hasn't changed. But I think there has been a loss of innocence for all of us," says Wendy Masi, a child psychologist and associate dean of the Family and School Center at Nova Southeastern University in Davie.

"The idea that it might be dangerous to let a child watch a video game or a store TV display while you shop a few aisles away, I don't think was in our collective consciousness before, and it's probably a good thing that it is."

Says Hawkins, who was instrumental in the creation of Missing Children's Day and keeping the message alive: "Without trying to alarm the parents, you have to tell them that 20 years later, Adam Walsh is still a never-ending story."

Jonathon King can be reached at

jking@sun-sentinel.com or 954-356-4691.

Chart: 20 years remembered - A timeline of events surrounding the disappearance

of Adam Walsh.

BOX: About this series

TODAY

Adam Walsh's abduction and murder changed the way America dealt with

missing children's cases, touching institutions from law enforcement

to business to Congress.

MONDAY

For John Walsh, Adam's death brought celebrity, a livelihood and the

reward of helping hundreds of other crime victims.

TUESDAY

Lost evidence. Sloppy police work. The death of the prime suspect. After

20 years, one of South Florida's most notorious crimes has never been

solved.

HECK FOR LIVE-IN PERIL

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

January 20, 2002

Florida's child-abuse deaths often have something in common besides

tragedy. Call it the paramour factor.

Department of Children and Families

officials use the term, which means lover, to describe live-in individuals

with little or no family connection to a child in the home. Paramours

can be men or women, but usually, they're men.

In the case of Joshua Saccone, the 2-year-old West Palm Beach boy who

died in 1999, the term describes Marguerite Saccone's boyfriend, Lincent

Chin. In the case of 8-year-old Joey Torres, who died in Hobe Sound

two years ago, it describes Tammy Huff's live-in boyfriend, Bradley

Dial. When 4-year-old Dylan Cassone died in 2000, his crack-addict mother

was living with a man who physically abused her.

DCF officials are paying more attention to the paramour's role in child abuse, though in terms of statistics, the problem would appear to be small. Of 220,695 reported abuse cases last year, the agency says, paramours were the perpetrators fewer than 2,000 times. When the Florida Department of Health analyzed child deaths, taking 30 cases from 1999 and 30 from 2000, the paramour was the killer eight times in each year.

These admittedly imprecise figures, however, don't show the true danger of violent men. Remember Bradley McGee, the Lakeland toddler who in 1989 was dunked head-first in a toilet until he was dead? The killer was a stepfather, Thomas Coe. In the 1994 death of 7-year-old Christina Holt of Riviera Beach, the killer was stepfather John Zile. DCF figures from 1999 show that a father or stepfather was the killer in 35 percent of cases, the mother in 28 percent and the paramour in 15 percent.

Paramours reflect the vulnerability of many young, poor, desperate mothers who, for economic reasons or to meet other needs, live with questionable men. In time, the man may view her child as an impediment to their relationship, especially if it's not his child. If he gets drunk one day and the baby won't stop crying, the child is in serious danger.

"Secretary (Kathleen) Kearney has made it clear that when there's a paramour in the home, abuse investigators should consider it a risk factor," says DCF spokeswoman Cecka Green. Investigators are told to ask more questions. Does he help pay bills? What is his role with the children? Is he ever alone with them? If he seems to pose a threat, DCF may tell the mother not to allow him involvement with her children or the state will take them into custody.

Some paramours wouldn't dream of hurting a child. Others fill a need for child care that the state-subsidized program doesn't, especially when mothers need care evenings or weekends. When abuse is alleged, however, and a paramour's in the picture, it's increasingly a red flag that no one in DCF can ignore.

IN COURT

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

January 31, 2002

WEST PALM BEACH - Convicted child killer Pauline Zile has a right to

an attorney and for a judge to hear further argument that her trial

attorney did not effectively represent her, a defense attorney told

Circuit Judge Jack Cook Wednesday. Robert Gershman said there are pending

motions in Zile's case that have not been heard. Prosecutors countered

that Zile has no right to an attorney because all pending matters have

been ruled upon. Cook scheduled another hearing. Since her 1995 conviction

for first-degree murder, Zile has unsuccessfully appealed it up to the

Florida Supreme Court, which let stand her life sentence for the 1994

death of her daughter, 7-year-old Christina Holt.

MOM APPEALS CONVICTION

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

February 23, 2002

Author: Gary Kane, Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Clutching a fat file of court records Friday, Pauline Zile resurrected

her claim that her attorney's blunders sent her to prison for life for

the 1994 death of her 7-year-old daughter.

Zile, who entered the courtroom

in hand and leg cuffs, listened intently as attorneys argued the merits

of devoting any more time to assessing whether Miami attorney Ellis

Rubin did an adequate job defending her in the 1995 murder trial.

Circuit Judge Jack Cook said he would review several of Zile's written

motions before making a decision on whether to conduct a hearing into

her claim.

Zile was convicted of first-degree murder in the death of her daughter, Christina Holt. John Zile, the child's stepfather, was convicted of the same charge and also is serving a life sentence. He was accused of beating Christina to death in their Singer Island apartment and Pauline Zile was accused of helping concoct a story that the child was kidnapped at a Broward County flea market. The child's body was found buried behind a Kmart in Tequesta.

Several of Zile's claims about Rubin have yet to be considered by any judge, said Robert Gershman, her court-appointed lawyer.

Assistant State Attorney Zareefa Khan argued that Zile be denied further use of a court-appointed attorney.

gary_kane@pbpost.com

STOP PROTECTING SYSTEM THAT FAILS

STATE CHILDREN

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

May 9, 2002

The Florida Department of Children and Families has failed. It isn't

the first time, but it's the worst time. The Rilya Wilson case is the

most egregious example of the agency's incompetence, and that's saying

something. Florida's child-welfare system arguably is the worst in the

nation, and it's folly for Gov. Bush to think it can be reformed from

within. He needs to fire DCF Secretary Kathleen Kearney, clean out the

top management and bring in outsiders before more children disappear

and die.

Rilya Wilson, a 5-year-old girl

under the state's protection, disappeared more than 15 months ago from

a Miami foster home, and nobody noticed. When DCF employees did realize

it, as early as April 19, they did not notify police until April 25.

During that time, as they searched for Rilya, they asked the DCF office

in Tallahassee for "guidance" in handling what they knew would

be bad publicity. The first job for those who take over the system must

be to shift the priority from secrecy and spin control to child safety.

DCF had removed Rilya from a drug-addicted mother and placed her with

Geralyn Graham, whom they thought was the child's grandmother. In January

2001, Ms. Graham said, a woman claiming to be a DCF worker took Rilya

for testing. When the girl didn't return, Ms. Graham said she asked

the girl's caseworker about her but could learn nothing.

Police and prosecutors are treating the case as a possible homicide. Exactly how the Department of Children and Families lost Rilya still is being investigated, but the caseworker, Deborah Muskelly, resigned in March after she allegedly falsified files and was told she would be fired. Ms. Muskelly's job was to report to the court on Rilya's status. Two months after the girl last was seen, however, she told Miami-Dade County Circuit Judge Cindy Lederman that Rilya was in day care. On Monday, Judge Lederman called DCF's handling of the case "absolutely despicable."

Ms. Kearney, a former Broward County judge, flew to Miami and announced policies that should have been in place, such as the keeping of logs to document home visits by caseworkers. Ms. Kearney did acknowledge that her agency had failed. But according to The Miami Herald, she also blamed "pundits" and child advocates for destroying public confidence in her agency by insisting that children are unsafe.

The facts, however, speak for themselves. The Legislature's Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability reported in 2001 that DCF was not meeting standards set by the Legislature for keeping children safe. The number of children who suffered mistreatment in foster care, the report said, had risen every year since 1998. Ms. Kearney became secretary in January 1999, when Gov. Bush took office.

DCF also has been the target of several scathing grand-jury reports, including two recent ones in Palm Beach County. This spring, The Orlando Sentinel obtained a disturbing internal audit of DCF's operations in Orange, Seminole, Osceola and Brevard counties. According to the report, administrators are so hampered by sloppy and incomplete paperwork that they cannot tell in three out of every 10 cases whether foster parents are capable of handling abused children DCF gives them.

House Speaker Tom Feeney, R-Oviedo, who represents the area, appointed a committee to look into the audit's allegations, which included overbilling and inappropriate placements of children at Orange County's mental-health center, Lakeside Alternatives. The committee, chaired by Rep. Sandra Murman, R-Tampa, also will scrutinize DCF's controversial deal with a private firm, Florida Task Force for the Protection of Abused and Neglected Children.

Last year, DCF contracted with the company to investigate 1,000 backlogged child-abuse cases and, if the children were safe, close them. In March, the agency abruptly canceled the arrangement - including a $351,000 contract with the district that includes Martin, St. Lucie, Indian River and Okeechobee counties - after allegations that the firm pressured workers to close cases. Payment was based on cases closed. There also were concerns about cases not being investigated fully.

Ms. Kearney said that while Rilya's case was "unbelievably tragic," it was an "isolated case." Not so, said Karen Gievers, a Tallahassee attorney who for more than a decade has been a blessedly persistent advocate for Florida's overlooked children. In June 2000, Ms. Gievers and a team of attorneys, including Bob Montgomery and Ted Babbitt of Palm Beach County, filed a class-action lawsuit in federal court charging that DCF is "the biggest abuser, neglecter and exploiter of children in Florida." The team has been taking depositions in Tallahassee and throughout the state. What it has heard, Ms. Gievers says, reflects a culture that is more protective of itself than of children.

Money always has been an issue when it comes to child welfare in Florida. Poor children have no clout in Tallahassee, and for decades, few lawmakers paid attention to pleas for more money to protect them. That changed somewhat under Ms. Kearney. The Legislature provided enough money so that no DCF caseworker would oversee more than 17 children. The reality, Ms. Gievers says, is that caseloads remain high. So where's the money going?

Obviously, protecting children in homes rife with violence and substance abuse is enormously difficult. For DCF, hiring and keeping protective investigators to go into those homes is a constant struggle. So is finding good foster homes with adults who don't do it solely for the money. As the state has grown, so has child abuse. Between 1993 and 2001, the number of children in state care increased from 14,800 to more than 20,000, according to the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration.

This week, however, Gov. Bush has used those numbers to dodge the accountability his administration preaches but rarely practices. On Monday, he called DCF an "imperfect system" dealing with "imperfect families." As everyone knows, that's old news. Then he appointed yet another "blue-ribbon panel," which will tell the governor nothing new but gives the impression of action. Wednesday, he defended Ms. Kearney and claimed that all children in state custody would get a visit by day's end. Rilya Wilson won't. He also told reporters that Floridians couldn't expect too much from the system.

He sounded quite different 3 1/2 years ago. Responding to a lawsuit over DCF problems in Broward, the newly elected Gov. Bush stood before a federal judge and pledged to fix them. He and Ms. Kearney had a plan. Within six months, he promised, Broward DCF officials would find families for 200 abused children in crowded foster homes and cut in half the number of children who have been moved more than twice in six months. Then they would move on to improve the system statewide.

Instead, the system is worse. In the four years before Ms. Kearney took office, there were an average of 25 child-abuse deaths in which the child was "known to the system," according to the National Coalition for Child Reform. During the first two years that Ms. Kearney was in charge, the figure rose to 31.5. Hundreds of children in state care - more than 400, by one count - are missing. DCF workers are supposed to report missing children to state and national registries and obtain a judge's order for law enforcement to pick them up, but they don't always do it.

Rilya Wilson is not just one little

girl lost. She is the latest in a litany of tragedies with names such

as Bradley McGee, Kayla McKean, Christina Holt, Joshua Saccone and Michael

Bernard. Gov. Bush needs to seek out models of child-welfare excellence

in other states, then hire independent experts to implement them in

Florida. The people and the culture that are the Department of Children

and Families have failed for the last time.

PULLING DARK SECRETS FROM THE

DEAD

Miami Herald, The (FL)

July 4, 2004

Author: JONATHAN ABEL, jabel@herald.com

Renfield is a fixture at the Sunrise Police Department's crime lab.

He's morbid. He's funny. He's

a skeleton, named after Dracula's servant who takes his master's coffin

from one point to the next.

Renfield is the creation of Charles Edel, a 23-year veteran of crime

scene investigations first with the Broward Sheriff's Office and now

with Sunrise police. Most people don't decorate their workplace with

skeletons, but then most people don't work in the grim, fascinating

world of CSI.

There are dozens of crime scene investigators in Broward, spread among the Hollywood, Fort Lauderdale and Sunrise police departments, not to mention the extensive BSO labs.

Like Dracula's servant, these men and, increasingly, women work in the shadows. They live from one death to the next and every day pass through new blood-splattered hallways en route to extracting secrets from the dead.

``I've seen somebody die in every form and fashion possible,'' Edel said while sipping a soda in the lab, which is why he hates the ``age-old'' question: ``What's the goriest thing you've ever seen?''

Despite the gore, Edel said his job is interesting, not depressing.

The silver-haired man turns to religion to handle the horror.

``I just have a good relationship with God,'' he said.

Edel leads a prison ministry at the Pompano Work Release Center. On Sundays, he works with troubled men. On weekdays, it's corpses.

``We talk for the dead,'' Edel said. ``We are the ones who find out what happened.''

From DNA analysis to digital photography, ``forensic science jumps in leaps and bounds every 10 years,'' Edel said.

But now, as when the 55-year-old first joined up, the field attracts precise and clever people who can absorb the ghastly details of the crime professionally - without absorbing them personally.

``Since you don't know the people, you just separate yourself. You couldn't do it if you knew the deceased,'' said Carol Kovel, an investigator at the Fort Lauderdale Police Department. ``The only time it has bothered me is when it's kids, and then it's very difficult.''

She has not shaken the memory from the autopsy of two twin sisters who died in a house fire years ago. ``It looked like two angels there.''

HARD TO TAKE

Thomas Hill, her mentor at the Fort Lauderdale Police Department, said that child abuse is even harder to handle than murder. ``Little children . . . that just grinds me.''

He came across a case of a 3-year-old boy with chemical burns, bruises and scars. ``There was no doubt in my mind that if he was returned to his mother and whoever she was shacking up with, he was going to be killed,'' Hill said.

``So I wrote a letter to the governor and told him that it was in his lap - I'm letting you know up front that this kid is going to be killed if he's returned to this woman or man.''

Hill's steady voice flares with passion when he talks about this boy, but most of the time he succeeds at ``compartmentalizing'' the brutality he encounters in his work from his emotional life.

``You learn very quickly or you go nuts,'' he said. ``My wife thinks, `Oh, you're so cold.' No, I'm not. I'm keeping my sanity.''

NOT COLDHEARTED

This even spills over into tragedies he sees off-duty. ``You're just like, `OK, so what?' Tragedy happens and you don't react. Some people can construe it as being a coldhearted person and that's not it at all.''

CSI works on suicides, homicides, rapes, and child abuse, as well as other tragedies.

When a single-engine plan crashed in Fort Lauderdale on June 23, Kovel photographed the scene. ``It was interesting,'' she said. ``I haven't done a crash in several years.''

Many of the crime scene investigators have been drawn to CSI from more traditional law enforcement jobs. Edel worked as a beat cop till he got fed up with all the guesswork police used to investigate one particular shooting. He knew there had to be a more systemic and scientific way, so he went to CSI.

Hill used to process the forensic evidence of his scenes even before he joined CSI, back when he was on the burglary detail.

``I enjoyed being able to know that I had the guy by fingerprints when I went to interrogate him,'' he said.

He passed up retirement because he loves working over a good crime scene, taking it slowly and meticulously, combing through it for a shred of evidence.

TRACKING ROBBER

In a recent case, this shoe print specialist tracked down a serial robber savvy enough to wear a mask and gloves but not to cover his tracks.

``The victim said [the robber] had jumped over the counter. I processed the counter and made a positive ID on the shoe prints that the suspect was wearing.''

The rewarding part of the job, said Robert Foley, director of the Bureau of Criminal Investigation for the Plymouth County, Mass., Sheriff's Department, is using the hard evidence to get to the truth, even when that means contradicting eyewitness testimony.

Now working in Massachusetts after 15 years at BSO, Foley vividly remembers working on the Swap Shop kidnapping back in 1994 where forensic evidence led straight to the murderers of a little girl, Christina Holt.

``The parents had reported her possibly abducted from the Swap Shop,'' Foley said. ``We processed the apartment of the child in Palm Beach County and we discovered blood, which led to the conviction of both the mother and the father for murder.''

SHEER CRUELTY

Still, sometimes investigation is about documenting the sheer cruelty of crime rather than solving a puzzle.

The Fort Lauderdale police send Kovel to photograph women who have been raped and men suspected of doing it.

The worst scene she has ever processed was a homicide 13 years ago in a mobile home park. ``There was blood all over the trailer and no air conditioning,'' Kovel said.

She went home and dropped her clothes in the garbage can.

But the visceral stench of the job is the least of it. The horror of child abuse, by all accounts, takes much more to get free of than just throwing away one's clothes.

Investigators like Kim Pavlik steel themselves against thinking about the crimes when not on the job. She scuba dives and works on her master's degree in criminology in her spare time.

``When I was a paralegal, you lose sleep at night trying to worry about doing this, that or the other thing. Whereas here, you shouldn't take it home with you because some of the visuals are awful.

But this toughness takes time to develop.

``I didn't think I could do this job originally,'' Pavlik said. ``I used to faint at the sight of blood.''

STORIES OF ABUSE, CHILDREN'S NAMES

WILL ECHO FOREVER IN A COMMUNITY

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

May 19, 2005

Author: Emily J. Minor

There are certain names that stay with us. Adam Walsh. Forever 6 years

old.

Christina Holt. A.J. Schwarz.

Joshua Saccone.

These names that stick are often the names of children snapped away

unexpectedly. These local kids and their too-short lives were on my

mind this week as a high-profile trial ended in Palm Beach County, the

one where they wheeled in the little girl with the bright eyes, the

cute personality and the brain that was damaged because she was slapped

around so much.

Marissa Amora, named Moesha Sylencieux when she started off in life, has made headlines because of her rough lot. Abused as a toddler, left in a coma, she was later adopted by a foster mother who has made it her responsibility to take in special needs foster kids.

Dawn Amora not only gives these children love and attention. She gives them social justice, or at least she tries to.

A difficult view

This week, a six-member jury awarded Amora $35 million for the girl's suffering and care. Marissa was critically injured while her precarious living situation was under investigation by the state, and Amora's legal team argued that the state could have protected this child from harm.

You and I watch these cases with tender hearts and a fair dose of anger, but Detective Bob Falbe watches from a perspective that's hard to imagine. Falbe is with the sheriff's office and earns his paycheck investigating crimes against the elderly, crimes against children, sex crimes and missing children.

He wasn't involved in all of the most heartbreaking cases: Adam Walsh was abducted from a Hollywood mall as his mother shopped, then later murdered. Christina's mother and stepfather and A.J.'s stepmother are serving time in those children's deaths.

But Falbe was the investigator in another old case that's always fresh on my mind, one of those that stick: Joshua Saccone. Saccone is a little boy who's buried behind St. Mary's Medical Center, a boy who was fatally beaten about the same time Moesha was sent into a coma.

Jobs like Falbe's aren't always done in ideal conditions. In Saccone, the boy's mother, Marguerite, is in prison for turning her back to the problem. But the real criminal is her boyfriend, Lincent "Junior" Chin, who disappeared when the boy was admitted to the hospital near death.

'It's extremely frustrating'

Falbe thinks Chin threw the boy against the wall, but he's never been able to make an arrest. "Unless something drastically changes, I don't have enough to charge him," Falbe said Wednesday.

He put in a department request once to fly down and interrogate Chin - a Jamaican who he'd found held on drug charges in the Cayman Islands. But the travel money wasn't approved.

"It's extremely frustrating," says Falbe, who just keeps plugging along.

I guess when you have a job like his, there's plenty to keep you busy.

After a spate of these child welfare cases were botched in the mid-1990s, the state renamed the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services. It's now called the Department of Children and Families.

You can change the department name. You can change the letterhead and the artwork on the walls.

It's still the everyday people who continue to make the real difference - people like Dawn Amora, Detective Falbe, the occasional DCF caseworker, whose good work is so often overshadowed. People like those six jurors who sat in the windowless courtroom and listened to the story of a girl once named Moesha.

- emily_minor@pbpost.com

NOTED LAWYER ETCHED REPUTATION

IN CREATIVITY, AIDING UNPOPULAR -

ELLIS RUBIN 1925-2006

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

December 13, 2006

Author: RON HAYES, Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Ellis Rubin, the colorful and quotable defense attorney whose creative

arguments on behalf of his clients always brought publicity, if not

acquittals, died early Tuesday at his Miami home. He was 81.

Mr. Rubin, who battled cancer

for more than six years, had known death was near and reacted characteristically.

He alerted the press.

"I'm afraid this is it," he said Wednesday from Mount Sinai

Medical Center in Miami Beach. "I just wanted to say goodbye to

everybody."

During five decades as a defense attorney in South Florida, Mr. Rubin represented more than 5,000 civil and criminal cases and gained a reputation as a lawyer who was not afraid to defend unpopular defendants or offer imaginative arguments.

In Palm Beach County, Mr. Rubin was best known for his 1995 defense of Pauline Zile, accused of murder for her role in the beating death of her 7-year-old daughter, Christina Holt, at the hands of her husband, John Zile. Mrs. Zile had appeared on television, claiming the child was kidnapped, even though she knew the girl was dead.

Mr. Rubin's argument that his client was only a "minor player" in the crime did not save her from a first-degree murder conviction, but he managed to have her sentenced to life in prison rather than death.

Mr. Rubin first gained national attention in 1977, when he defended Ronny Zamora, a 15-year-old Miami boy accused of murdering an elderly neighbor during a robbery. In one of the nation's first televised trials, Mr. Rubin argued that the boy's reason had been dulled by nearly incessant television viewing, dubbed the "television intoxication defense." The jury was not persuaded, and Zamora served 27 years in prison.

In 1989, Mr. Rubin co-wrote an autobiography, Get Me Ellis Rubin!, in which he boasted of his maverick reputation.

In 1991, Mr. Rubin was in the national spotlight again when he took on the cause of Jeffrey Willets, a Broward County sheriff's deputy charged with living off the earnings of a prostitute. The alleged prostitute was Willets' wife, Kathy, who claimed she was not a prostitute but a nymphomaniac.

"I intend to turn the courtroom into a classroom," Mr. Rubin promised. "I'm going to bring in medical experts to explain voyeurism, nymphomania, surrogate sex."

In the end, the Willetses pleaded guilty, and their lawyer wrote another book.

He often was accused of being a publicity hound, but Mr. Rubin defended his high-profile approach.

"If the prosecutor is going to try and charge them and condemn them on the 6 o'clock news," he said during the Willets trial, "you'd better get them an appeal on the 11 o'clock news, because everything the media writes and show makes an impression."

Mr. Rubin also freed a woman accused of bludgeoning her father to death with his use of the "battered woman" defense, helped lift the TV blackout of NFL games and challenged the state's ban on same-sex marriage.

He won his last case when a judge ruled that a Reform Party candidate for governor should be included in a debate. He was proudest, though, of the 37 days he spent in jail for refusing to drop a defendant he knew would lie on the stand.

Robert Barrar, who will continue the practice he had with Mr. Rubin, said, "He and I worked together for 17 years and we were partners for 11. He was a nice guy, a great partner, a good friend, great mentor. I'll miss him a lot. He taught me that, no matter how hard it gets in the courtroom, to stay cool because cooler heads always prevail."

In addition to his wife, Barbara Storer, Mr. Rubin is survived by four children and seven grandchildren.

The funeral will take place at 10:30 a.m. Thursday at Riverside Memorial Chapel, 1920 Alton Road, Miami Beach.

The Miami Herald contributed to this story.