Home --> Christina Holt's Story --> Christina Holt's Story: Newspaper Articles --> 1998

Christina's Story

- Newspaper Articles

The following links take you to various articles in Christina's story

as it appeared in the South Florida media.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE INFORMATION ON THIS SITE BEFORE ASKING.

Thank you!

|

|

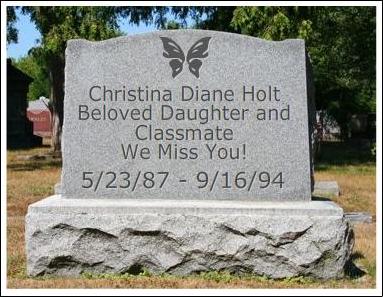

In Loving Memory Of May 23, 1987 - September 16, 1994 "Beautiful Child who has found love from the angels...RIP..." |

(Not her actual headstone) |

These

pages contain all of the articles from the Palm Beach Post and The

Sun-Sentinel throughout the years. |

|

Lawyer: Case Against

Zile Tainted (2/11/98)

Mom Struggles To Sustain Kids' Abuse Campaign (4/20/98)

Court Upholds Zile's Murder Conviction (5/21/98)

Court Upholds Zile Conviction For Failing To Save Daughter

(5/21/98)

In Court (6/12/98)

Attorney Plans To Appeal Zile Murder Conviction (6/12/98)

Saving Florida's Children -- Review Could Imperil Prosecution

(7/5/98)

Saving Florida's Children -- Prevention In Project's Goal

(7/5/98)

In Court (9/19/98)

Lawyer Getting $44,000 For Pauline Zile Appeal (9/19/98)

Another Little Girl Left To Her Fate (12/4/98)

LAWYER: CASE AGAINST

ZILE TAINTED

The Palm Beach Post

February 11, 1998

Author: Val Ellicott

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Some of the crucial evidence prosecutors used to convict Pauline Zile

of murdering her daughter was obtained improperly, Zile's attorney told

appellate judges Tuesday.

The attorney, Richard Bartmon, said police might never

have found out exactly how 7-year-old Christina Holt died or where she

was buried except that Zile's husband, John Zile, told them

And John Zile decided to talk only after police told him his wife had

already made a statement and that, based on that statement, he was being

charged with aggravated child abuse.

Telling John Zile about his wife's statement was a critical error, Bartmon told the three-judge panel Tuesday, because Pauline Zile had been promised limited immunity, meaning police were barred from using her statement to elicit one from her husband.

Prosecutors later used the information in John Zile's statement against Pauline Zile. Pauline Zile, 27, was convicted of killing her daughter by failing to protect her from John Zile, 35, who was convicted of killing Christina by asphyxiation while abusing her at the family's apartment on Singer Island. Both Ziles are serving life in prison.

Assistant Attorney General Melynda Melear said Pauline's conviction should stand. She said John's decision to make a statement had little or nothing to do with knowing his wife had made one.

MOM STRUGGLES TO SUSTAIN KIDS'

ABUSE CAMPAIGN

The Palm Beach Post

April 20, 1998

Author: William Cooper Jr.

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Kathy Forrester, a stay-at-home mom upset about the number of local

child abuse deaths in 1994, decided to do more than talk about the problem

with friends over coffee.

She volunteered to help launch Our Community, Our Children,

a nonprofit agency whose mission was to begin a massive child abuse

prevention campaign.

Initially, the group flooded the community with blue and white bumper

stickers, refrigerator magnets, T-shirts and tote bags promoting the

agency's theme, ``No Excuse For Child Abuse.''

Public service announcements filled radio and television - compliments of the media. Local donations, totaling about $30,000, paid for printing and distribution of information fliers.

Now, four years later, much of that momentum has waned, and Forrester is struggling to keep the agency's doors open.

The organization was born out of the deaths of Christina Holt in 1994 and A.J. Schwarz in 1993.

``This organization exists because those children died,'' said Forrester, who now is serving as an unpaid executive director of the agency. ``I had to pay my dues, but while I'm doing that, people need to know that children are still dying.''

The turning point for the nonprofit organization happened in the spring of 1996, when Forrester submitted a $160,000 proposal to the Children's Services Council, which uses tax money to pay for new children's programs.

Forrester wanted the money to pay for staff, develop a public awareness campaign and to distribute information packets about parenting. CSC rejected it, saying Forrester's goals seemed too ambitious for such a young agency.

After that setback, several board members left or just stopped coming to the meetings, said Steve Vooglesang, a local tax attorney and original board member.

``I think everybody was a little disappointed,'' Vooglesang said.

The rejection touched a nerve with Forrester. From the beginning, she quietly questioned whether she was the person to lead Our Community, Our Children.

She was a homemaker, with no college degree and no expertise in children's issues. Yet being a new mother drove her to get involved.

In a matter of months, she went from being a volunteer to leading an agency that was charged to educate the community about child abuse.

Forrester now is distributing the ``Parenting Pouch,'' an informational guide for new parents. It has resources, including telephone numbers where parents can get advice or counseling about raising their children.

``I don't care how many doors get slammed in my face, I'm not going to stop trying,'' Forrester said.

Currently, she's applied for grants from the Community Foundation of Palm Beach and Martin counties and the Quantum Foundation so the agency can continue to distribute information about parenting tips and child safety to the community.

Over the years, the agency has survived on small grants from the Department of Children and Families. Corporate sponsors and efforts to raise money never have reached the group's initial expectations.

Tana Ebbole, CSC's executive director, said the intent wasn't for her agency or any other governmental entity to be Our Community, Our Children's sole source of financial support.

``That's why we titled the organization the way we did . . . ,'' she said.

Ebbole believes people in the private sector often are uncomfortable with talking about child abuse and do not get involved financially. Their uneasiness leaves the bulk of the responsibility to government agencies.

``We need to have an aggressive, ongoing community awareness campaign on child abuse,'' Ebbole said. ``It's every citizen's responsibility to send a message that we will not tolerate children being abused or being killed.''

Recently, Forrester took steps to revive Our Community, Our Children. She's gone from running it from her Palm Beach Gardens home to a West Palm Beach office at 2247 Palm Beach Lakes Blvd.

She's recruited new board members and is negotiating with new corporate sponsors.

Toby Chabon, owner of Chabon and Associates, a career development and human resources consulting firm, now heads the board. Chabon brings nearly 20 years of child advocacy to Our Community, Our Children, including serving on the county's Foster Care Review Committee and as past president of the Center for Children in Crisis, a nonprofit agency that provides counseling for abused children.

``I like challenges,'' Chabon said. ``This is an issue we all must be involved in on a regular basis, not when we're just reacting to startling headlines.''

COURT UPHOLDS ZILE'S MURDER CONVICTION

HER CRIME WAS IN DOING NOTHING TO STOP DAUGHTER'S FATAL BEATING, JUDGES

RULE

Sun-Sentinel

May 21, 1998

Author: NICOLE STERGHOS Staff Writer

One of the first mothers in the nation to be convicted of murder for

failing to protect her child from abuse should remain in prison for

life, a West Palm Beach appellate court ruled on Wednesday.

Despite an aggressive, multipronged appeal, the 4th

District Court of Appeal upheld Pauline Zile's murder conviction and

life sentence in the 1994 beating and suffocation of her 7-year-old

daughter, Christina Holt.

It was among the first cases in the country where a parent was convicted

of first-degree murder for letting someone else abuse their child, even

though Zile herself did not lift a finger to strike Christina.

Prosecutors argued in the April 1995 trial that Zile's crime stemmed from her refusal to step forward to protect Christina as her husband, John Zile, beat her unconscious.

In one of the first legal tests of that theory, appellate judges sided with the state, decreeing Pauline Zile's inaction criminal in the face of her daughter's suffering.

In their seven-page opinion, the judges said jurors could legitimately find Zile guilty of murder.

"The jury could have determined that [Zile) failed to execute her duty to protect the victim by standing by and allowing John to punish the victim so severely," the appellate judges wrote.

"[Zile) allowed the assault to continue until the child lapsed into unconsciousness, at which time [Zile) said `That's enough, John,' in a calm and quiet voice.

"The jury could have found that the evidence suggested that [Zile) approved and condoned the attack up until the victim lost consciousness, and willfully intended the beating or torture to continue."

The judges granted Pauline Zile a minimal victory, overturning one of three additional aggravated child abuse convictions, each of which held 13-year sentences.

But because Zile is serving those sentences concurrently with her life term, the reversal will not affect her length of stay in prison.

"We're disappointed with it," said Zile's appellate attorney, Richard G. Bartmon of Boca Raton.

Christina died on Sept. 16, 1994, as her stepfather was holding his hand over her mouth and beating her for defecating on the floor of the family's Singer Island apartment.

Though John Zile tried to revive Christina through CPR and by placing her in a bathtub full of water, his efforts were fruitless. The Ziles then hid the little girl's 44-pound body in a bedroom closet for four days, masking the stench with strawberry incense.

They sold her videotapes and bicycle to help buy a shovel and tarp, which they used to bury her behind a Tequesta K-Mart.

About a month later, the Ziles concocted a bogus story to explain Christina's disappearance. Holding what she said was her daughter's teddy bear, Pauline Zile tearfully went before television cameras to say the girl had been kidnapped from a Fort Lauderdale flea market.

"Of all the cases I look back on, I think this one tore up our community more than any other in recent memory," said Nancy McBride, executive director of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. "She has become the symbol of a child who deserves so much and got so little."

Like many others who followed the case from its infancy, McBride blamed Pauline Zile for standing idly by as much as she blamed John Zile for dealing the vicious blows.

"She was the biological mother and she did nothing," McBride said.

"So I've always held her just as accountable as John Zile, and she should be punished in the same manner."

John Zile is also serving life in prison for murder and child abuse convictions in the case. He, too, is appealing.

The appellate decision in Pauline Zile's case comes at an appropriate time for McBride and her organization, which on Friday will dedicate a display board at its office in Lake Park to Christina's memory.

The display board holds fliers of missing children.

For Dorothy Money, Christina's great-grandmother and the one who raised her from infancy to just a few months before her death, the appellate decision was cause for celebration.

"That's wonderful," Money said from her Maryland home. "I haven't drank in years, but I'm going to have me a shot of whiskey to celebrate."

Bartmon, Zile's attorney, waged the appeal on several fronts, arguing that the trial should have been moved because of excessive publicity, that evidence in the case was not properly thrown out and that prosecutors used Zile's statement to police against her, even though they promised not to.

The appellate judges disagreed, spending much of their opinion disputing whether Zile's statement was used against her. It was not, they concluded, because police had independent sources to support the evidence they obtained.

COURT UPHOLDS ZILE CONVICTION

FOR FAILING TO SAVE DAUGHTER

The Palm Beach Post

May 21, 1998

Author: Val Ellicott

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Pauline Zile's failure to prevent her daughter's fatal beating in 1994

qualifies as torture under Florida law and justifies her conviction

on first-degree murder, an appellate court ruled Wednesday.

Zile ``knew that the abuse was taking place, it was

in her presence, and even the neighbors heard the victim's screams and

her muffled voice after John (Zile) covered her mouth,'' the 4th District

Court of Appeal wrote.

The judges rejected Zile's arguments that her trial should have been

moved outside Palm Beach County due to publicity and that she was convicted

of killing 7-year-old Christina Holt based, indirectly, on information

she revealed after being promised immunity.

The court did reverse Zile's conviction on one of three counts of aggravated child abuse, deciding that, in one instance, Zile, 27, wasn't even in the same room when her husband, John, struck Christina with a belt at the family's Singer Island apartment.

That acquittal will not affect Zile's sentence of life with no chance for parole.

Richard Bartmon, the attorney handling Zile's appeal, said he may ask the appellate court to reconsider its decision upholding Zile's other convictions. An appeal to Florida's Supreme Court also is an option, he said.

The appellate court said Zile's failure to act when John Zile began striking Christina on Sept. 16, 1994 - the night of the fatal beating - qualifies as a form of torture under state law.

Torture is a legal element of aggravated child abuse, the charge used to convict Zile of first-degree felony murder. Under Florida law, Zile was guilty of murder if she committed a felony that resulted in Christina's death.

``We're very happy that they (the judges) upheld the state's theory for convicting somebody, under these facts, for not doing anything,'' prosecutor Scott Cupp said.

In arguing Pauline Zile's appeal in February, Bartmon said John Zile gave police information that incriminated both him and his wife, but only after police told him his wife had made a statement herself.

That was improper, Bartmon said, because Pauline Zile had been promised limited immunity, meaning police were barred from using her statement to elicit one from her husband. But the appellate judges said there was no evidence that John Zile's decision to talk to police was influenced by his wife's statement.

``John Zile was already a suspect before (Pauline Zile) gave her statement,'' the judges said. They also noted that Pauline Zile's conviction was supported by other evidence.

IN COURT

The Palm Beach Post

June 12, 1998

WEST PALM BEACH - Boca Raton attorney Richard Bartmon was appointed

by a judge Thursday to represent Pauline Zile, at taxpayer expense,

in asking Florida's Supreme Court to review Zile's first-degree murder

conviction in the 1994 death of her 7-year-old daughter, Christina Holt.

Last month, the 4th District Court of Appeal rejected Bartmon's arguments

that Zile's conviction be overturned. The court ruled that Zile's failure

to protect her daughter from a fatal beating by Zile's husband, John.

ATTORNEY PLANS TO APPEAL ZILE MURDER CONVICTION

Sun-Sentinel

June 12, 1998

Author: Staff reports

Pauline Zile's attorney told a judge on Thursday that he plans to appeal

his client's murder conviction to the Florida Supreme Court.

Zile, the first mother in the nation to be convicted

of first-degree murder for failing to protect her child from abuse,

is serving a life sentence after her husband beat and suffocated her

daughter, Christina Holt, in October 1994.

Last month, the 4th District Court of Appeal in West Palm Beach upheld

the bulk of Zile's conviction and sentence, throwing out only an unrelated

child-abuse conviction.

In a brief hearing on Thursday, Circuit Judge Howard Berman granted a request by Zile's court-appointed attorney, Richard Bartmon, that he be allowed to stay on the case while he seeks review from the state Supreme Court.

County Attorney Dan Hyndman had objected, saying the county should not be obligated to pay Bartmon's fees because Zile does not have a constitutional right to appeals beyond the 4th District.

SAVING FLORIDA'S CHILDREN

REVIEW COULD IMPERIL PROSECUTION

The Palm Beach Post

July 5, 1998

Author: Barry Krischer

It is the clear intent of the Florida Legislature, and a benefit to

our society, that we recognize the reality of child abuse and neglect.

It is only through meaningful review and investigation of all reported

incidents - and the proper education of their parents, where appropriate

- that we can ensure the safety of all children. Likewise, the regular

review of all child deaths needs to be the goal of our county and state.

And the state of Florida is headed down that road.

The Department of Juvenile Justice gave the Department

of Children and Families a grant to improve services to Florida's children.

As part of the grant, a task force has been appointed to create a strategy

for a statewide child fatality review. Dr. J.M. Whitworth, executive

medical director of the Children's Crises Center in Jacksonville, will

lead the study group.

The group has been conducting an analysis of the issues for more than

six months. Along the way, it has reviewed methodologies with an eye

toward achieving a uniform, statewide collection of data pertaining

to all child deaths. It is this latter goal that is critical to the

selection of the proper method of review.

We need a simple but complete method of data collection that can be applied realistically in all jurisdictions, large and small, including those with minimal resources, that will ensure the review and analysis of every child younger than 18 who dies in this state. This can only be achieved by the creation, and use, of a minimum standard data set. That is, in every case, certain basic questions must be asked and answered. This is the core issue where the statewide study group and the local deathreview committee part company.

In simplest terms, the way the local child fatality review project intends to interview parents of the deceased child is a dangerous practice as viewed from a law enforcement perspective. Granted, fewer than 5 percent of all child deaths are criminal homicides, but the promise of confidentiality to an individual who, through subsequent investigation, is determined to have been the perpetrator of the child's death could endanger a future prosecution. The current local review team has as its goal a process that is neither confrontational nor accusatory. Recognizing the reality that parents, siblings and caretakers, do, in fact, kill their children, this is not a realistic approach.

That is not the sole reason to reject this approach. The current review team can conduct an in-depth review of only a sampling of child deaths. While its protocol should be applauded, it is so in-depth that it does not lend itself to a review of every child death in the county. This is a critical issue if this project is to succeed.

It is the proper identification of child abuse that can and should lead to effective remedial action for the surviving children of that family. By reviewing every death, the fatality review team plays a pivotal role in the reduction of further abuse and the creation of a basic set of information that has value in the area of prevention.

Children die for a range of reasons, and now there is no central, uniform nor complete database of information with regard to these children. In fact, as of today, no one knows with any degree of accuracy how many children die each year in Florida.

Children die due to neglect to provide for their basic needs: food, clothing, shelter, medical care. Children also die as a consequence of a well-meaning parent's intervention with a home remedy, rather than seeking medical attention. There is also the very real possibility of a truly accidental death. Children also simply get sick and die.

Additionally, there are gaps and deficiencies in the delivery of services to children and their families by public agencies that may be related to the cause of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. These and other possibilities cry out for a uniform method of reviewing all deaths to ensure that we learn from these tragedies and to prevent and reduce their incidence in the future.

The statewide study group recognizes the need for providing information to a statewide database and the need to review all child deaths using the minimum data set. It also recognizes that every community is different, so the group needs to be flexible to meet the local team's needs and plans for its own community, keeping in mind the core goal of the project.

Toward these ends, the statewide study group has formulated the following statement of policy:

1. Every child is entitled to live in safety.

2. Responding to child deaths is a state and a community responsibility.

3. When a child dies, the response by the state and the community to the death must include an accurate and complete determination of the cause and manner of death, and the development and implementation of measures to prevent future deaths from similar causes.

4. Professionals from disparate disciplines and agencies who have responsibilities for children and expertise that can promote child safety and well-being should share their expertise and knowledge so that the goals of determining the causes of children's deaths, and preventing future child deaths, can be achieved.

These shortand long-term goals cannot be reached by a process that focuses on prevention only. It has to point out mistakes or neglect. The local review team perceives that the inclusion of law enforcement in the review of child deaths makes the review a "finger-pointing" tool. The group opted for a non-punitive approach because it believed there are enough agencies focusing on criminal aspects of child deaths.

The group perceives that its mission of preventing child deaths through education, analysis and policy changes needs to be achieved without the involvement of law enforcement. This narrow view has been rejected by the statewide child death study group.

The benefits of a statewide policy to review every child fatality is too obvious to require justification. Only when the who, what, where and when of the death are uniformly and consistently answered correctly, however, can all the proper legal, medical, safety and child protection issues that arise at death be handled expertly and completely for the administration of justice and the reassurance of the community.

No policy will have much effect if communities are not provided with money adequate to collect the data needed for statewide application. Financing for the education and training of death review teams will be needed to ensure uniform compliance and data collection. Anything less will be yet another unfunded mandate.

State Attorney Barry Krischer originally expected to play a key role in Palm Beach County's Child Fatality Review Project. But last month, he resigned from the group, saying its nonjudgmental method of investigating deaths is flawed. Mr. Krischer became active instead in the 26-member statewide task force, which he says preserves an important law-enforcement component.

Dr. Jean Malecki, Palm Beach County's health department director and local project chairwoman, says her group's approach, which includes confidentiality for those interviewed, will do a better job of uncovering detailed information that can be used to prevent deaths.

The Palm Beach Post asked Mr. Krischer and Dr. Malecki to explain their differing approaches to saving children.

Barry Krischer is Palm Beach County's state attorney.

SAVING FLORIDA'S CHILDREN

PREVENTION IS PROJECT'S GOAL

The Palm Beach Post

July 5, 1998

Author: Jean Malecki

Statistics for child fatalities in Palm Beach County are not just numbers.

Behind each number is a child. A child whose life was precious. A child

who had a future. A child who was loved - by someone.

We often hear where there is life, there is hope. The

lives of these precious children are gone. Their remaining hope is for

us, the community, through the Child Fatality Review (CFR) Project,

to learn from their lives and deaths how to stop the tragedy of preventable

deaths.

Initially driven by community concern about deaths due to child abuse

and neglect, the Child Fatality Review Project focuses on the prevention

of childhood deaths from all causes, including unintentional injuries,

homicides, suicides and natural causes. The project looks to identify

risk factors in order to prevent the deaths of other children.

The Palm Beach County Child Fatality Review Project focuses on all childhood deaths, not suspicious deaths alone. CFR is not focused on a law-enforcement response to those deaths. It will examine cases that have been closed by criminal justice, so as not to interfere in the judicial process. Parents and significant others who agree to be interviewed by CFR staff will first be asked to sign a consent which includes the statement that if information revealing child abuse or neglect is found, CFR

There is an important place for rapid law-enforcement response with access to known information from all sources and for internal reviews by the Department of Children and Families. However, the Palm Beach County Child Fatality Review must preserve the valuable non-blaming, needs-assessment and quality-improvement approach. Our community will benefit from the existence of all of these - from a multi-faceted approach. Using qualitative information, such as the family experience and that ofother significant respondents, rather than data pieces alone, will be most valuable in preventing deaths. A local CFR project will enable Palm Beach County to address local needs, while contributing to and benefiting from information gathered statewide and in other states.

If, because of staff limitations, CFR can't review 100 percent of childhood deaths, the team will use a selection process that accounts for all types of deaths and ages under a scientific model. CFR will ensure that strict confidentiality, sensitivity to grieving parents and family, and sensitivity to cultural issues are considered in all that we do.

The project is under the direction of the Palm Beach County Health Department, where project staff and community committee members are protected from liability by state law. The money comes from: Quantum Foundation, Children's Services Council and the Healthy Start Coalition. Additional sources of financing are being sought.

A steering committee of community agencies and sponsors provides project oversight and will be the springboard for community actions resulting from recommendations of the project's three Case Review Teams, staff and the community. A Community Action Team will work to turn the project's recommendations into actions. These actions will help the community protect children and prevent further child fatalities and injuries.

The project's goal is to reduce the number of children who die in Palm Beach County by conducting a comprehensive review of individual child deaths, designing and coordinating prevention efforts, evaluating those efforts and the way prevention money is spent, and recommending policy changes.

The project will work closely with the Healthy Start, Safe Kids and Drowning Prevention coalitions, as well as the medical examiner's office and the Trauma Agency of the Palm Beach County Health Care District.

The project, which began in April, is scheduled to begin operating this month. It uses the Fetal/Infant Mortality Review model (which analyzes deaths of fetuses and infants) to track cases, works closely with the Florida Department of Health Child Fatality Review Project staff, and incorporates the county's 4-year-old Fetal/Infant Mortality Review project while expanding the focus from infancy to 18 years.

CFR projects in Arizona, California and Missouri were used as reference models. The Palm Beach County CFR project goes a step further with interviews of parents and significant others, such as friends of teenagers. The interviews are conducted at least three months after the death of the child and include referral to community resources for bereavement counseling and support.

About 30 community agencies and groups are participating in the project. Among them: the Children's Services Council, Compass Inc., the Department of Children and Families, the Department of Juvenile Justice, the Florida Highway Patrol, Home Safe, Hospice, the sheriff's office, the medical examiner's office, the Mental Health Association, fire/rescue, the school district, St. Mary's and Delray Medical trauma centers and prosecutors.

We are very encouraged by the outpouring of interest, support and committed involvement that the Child Fatality Review Project is receiving. Together we will make a positive impact on the health and safety of children in Palm Beach County through prevention.

Together we will make "Palm Beach County - a safer place for kids!"

State Attorney Barry Krischer originally expected to play a key role in Palm Beach County's Child Fatality Review Project. But last month, he resigned from the group, saying its nonjudgmental method of investigating deaths is flawed. Mr. Krischer became active instead in the 26-member statewide task force, which he says preserves an important law-enforcement component.

Dr. Jean Malecki, Palm Beach County's health department director and local project chairwoman, says her group's approach, which includes confidentiality for those interviewed, will do a better job of uncovering detailed information that can be used to prevent deaths.

The Palm Beach Post asked Mr. Krischer and Dr. Malecki to explain their differing approaches to saving children.

Dr. Jean Malecki is director of the Palm Beach County Health Department.

IN COURT

The Palm Beach Post

September 19, 1998

WEST PALM BEACH - Circuit Judge Howard Berman Friday ordered the county to pay $44,000 to attorney Richard Bartmon for handling the appeal of Pauline Zile. Assistant County Attorney Daniel Hyndman objected to the bill and called an expert who said a fee of about $30,000 would be appropriate. Bartmon testified that he has extensive appellate experience, including nearly four years as an assistant attorney general handling first-degree murder cases. Bartmon, who will be paid an hourly rate of $75, said he spent 587 hours working on Zile's appeal. Zile was sentenced to life in prison for her role in the 1994 death of her 7-year-old daughter, Christina Holt. In May, an appeals court rejected Bartmon's arguments that Zile's conviction be overturned. Zile's failure to protect her daughter from a fatal beating by Zile's husband, John Zile, qualifies as torture under Florida law, the appeals court ruled.

LAWYER GETTING $44,000 FOR PAULINE ZILE APPEAL

Sun-Sentinel

September 19, 1998

Author: Staff reports

Over the objection of county officials, a Palm Beach County judge on

Friday approved a public payment of $44,000 to a court-appointed attorney

who fought, and lost, an appeal of Pauline Zile's murder conviction.

Zile, the first mother in the nation to be convicted of first-degree murder for failing to protect her child from abuse, is serving a life sentence after her husband beat and suffocated her daughter, Christina Holt, in October 1994.

Attorney Richard Bartmon appealed, but the 4th District Court of Appeal upheld the conviction. Bartmon plans to appeal to the Florida Supreme Court.

ANOTHER LITTLE GIRL LEFT TO HER

FATE

The Palm Beach Post

December 4, 1998

Author: Candy Hatcher

Christina Holt must be turning in her grave.

Law enforcement officers unearthed another child's battered

body this week after hundreds of volunteers spent days searching for

the little girl lost in Central Florida. They put another father in

jail who first said his child had disappeared one morning, then confessed

he had gotten angry and killed his 6-year-old because she had soiled

her pants. Then, once again, people who had seen the violent father's

attempts at discipline in the months before piped up and said, Yeah,

we suspected something was wrong in that home.

Did we learn nothing from Christina's wrenchingly similar story four

years ago?

The picture of the pixieish 7-year-old and the horrors we know of her life and death should be seared in our memories: How she was passed among family members and wound up in Florida, in the custody of a mother who didn't want her and a stepfather who abused her. How she soiled her pants one night, so enraging her stepfather, John Zile, that he hit her in the face, beat her until she went into convulsions and died.

How, weeks later, Christina's mother clutched a doll and cried that her little girl with the big brown eyes had disappeared from a Fort Lauderdale flea market. After law enforcement officers had spent days searching the area and scuba divers had scoured a nearby canal, Christina's stepfather admitted he had killed the girl and buried her behind a Kmart.

Neighbors had heard a child's screams and the sounds of beatings in the Ziles' Singer Island apartment but had not told anyone who could have helped. Christina had been absent from school all but four days of a six-week period, but no one alerted authorities.

What is it about a missing-child report that causes people to leave work and search for a child they've never met? Why don't we see that same concern over the child next door, or the one in the emergency room, or the one in day care who shows up with black eyes and bruises? What keeps us from stepping in to help frazzled parents, perhaps finding a counselor for one unable to control his anger, or at least reporting bruises to the child welfare agency? What keeps professionals from following up when they see evidence of child abuse?

In the case of 6-year-old Kayla McKean, all the signs were there. She went to live with her father and his wife in April. A month later, she was taken to an emergency room with two black eyes, a swollen and fractured left hand, a fractured nose and hemorrhages of the eyes. Child welfare workers in Lake County, northwest of Orlando, told a judge only about the black eyes. Kayla's father, Richard Adams, said she had fallen off her bike the previous week. The judge sent Kayla back home.

The following month, Kayla went to a doctor for treatment of an eye injury. She had bruises all over her body. Adams admitted he had hit the child with a paddle but denied bruising her. Although the doctor believed Kayla was "in imminent danger while in his care," no investigator interviewed him. Kayla remained with her father. A month before she died, Kayla had a bump on her head, black eyes and bruises on her chin. Her father blamed the injuries on a fall in the bathtub and the family dog stepping on the girl.

When her father reported Kayla missing Thanksgiving morning, hordes of strangers began combing through muck and brush, searching for a child they hoped simply was lost. Police detectives carried pictures of Kayla in their pockets. When police announced that the child's father had confessed to killing the girl, hundreds showed up at a candlelight vigil to remember her.

"The town really pulled together for this little girl," the police chief said. If the town had pulled together sooner, that little girl might still be alive.

And Christina's death might have served some purpose.

Candy Hatcher is an editorial writer for The Palm Beach Post.