Home --> Christina Holt's Story --> Christina Holt's Story: Newspaper Articles --> 1996 Page 16

Christina's Story

- Newspaper Articles

The following links take you to various articles in Christina's story

as it appeared in the South Florida media.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE INFORMATION ON THIS SITE BEFORE ASKING.

Thank you!

|

|

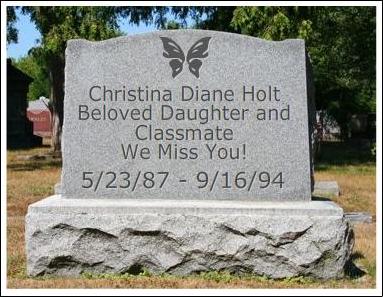

In Loving Memory Of May 23, 1987 - September 16, 1994 "Beautiful Child who has found love from the angels...RIP..." |

(Not her actual headstone) |

These

pages contain all of the articles from the Palm Beach Post and The

Sun-Sentinel throughout the years. |

|

Reporter Gets Fine,

70-Day Jail Term For Staying Silent On Zile Interview (10/8/96)

Herald Reporter Goes To Jail For Silence About Zile Story

(10/8/96)

Journalists' Group Condemns Jailing Of Herald Reporter

(10/9/96)

Save The Prosecutions For Crooks, Not Press (10/10/96)

A Case Of Ethics Vs. Pursuit Of Justice (10/11/96)

Lesson Being Lost: Journalists Serve Public Interest, Not

Government's (10/13/96)

Blame For Mistrials? Jury Out (10/13/96)

$180,000 Later, Zile's Third Trial To Open (10/14/96)

No Change Of Heart For Jailed Reporter (10/14/96)

HRS Will Lose District Chief After Nov. 15 (10/15/96)

REPORTER GETS FINE,

70-DAY JAIL TERM FOR STAYING SILENT ON ZILE INTERVIEW

Sun-Sentinel

October 8, 1996

Author: STEPHANIE SMITH Staff Writer

A Palm Beach County judge jailed a newspaper reporter for 70 days on

Monday for refusing to answer questions about a jailhouse interview

with John Zile, who is accused of murdering his stepdaughter.

Circuit Judge Roger Colton found David Kidwell, 35, of The Miami Herald in criminal contempt of court and also fined him $500.

But both the jail term and fine could be canceled if the reporter changes his mind about testifying before Sunday, Colton said.

Jury selection is scheduled for

next Tuesday in Zile's retrial for aggravated child abuse and first-degree

murder of his stepdaughter, Christina Holt, 7.

Kidwell, reading from a prepared statement, said his journalistic ethics

will not allow him to takes sides in a criminal prosecution, even if

the law says he must testify.

"I don't want to go to jail; I would rather go back to work this afternoon," Kidwell said. "But either way, when I do go back to work, I have to know I'm free to pursue all sides of a story without interference from the government."

After the contempt hearing, Kidwell was arrested and handcuffed immediately. A bailiff handed Kidwell's wife, Pat Dunnigan, his wallet and pager for safekeeping. He remained in the Palm Beach County Jail late Monday.

John Zile's attorneys have promised to explore Kidwell's journalistic ethics if he does take the witness stand for the prosecution.

Kidwell interviewed Zile in jail in November 1994 about the night Christina Holt died after a beating. Zile's attorneys say Kidwell lied to jailers to gain access to Zile by claiming he was Zile's friend.

Kidwell has been accused of using the same tactics to interview a woman who police said strangled her granddaughter and stored the body in her freezer in Broward County.

Kim Walsh-Childers, a journalism ethics professor at the University of Florida, said the use of deception can be justified only if other methods to gain the interview failed and the story is of great public importance.

While the public may be curious about what a murder suspect has to say, there is not as strong an argument that the information is of public necessity, she said.

"I'm much more comfortable with his refusal to testify than how he got the interview," Walsh-Childers said.

If Kidwell serves the full 70 days for contempt, it would be the longest jail term served by any journalist, said Jane Kirtley, executive director for the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press in Arlington, Va.

Nationally, more reporters are being subpoenaed for criminal cases.

Kidwell's attorney, Sandy Bohrer, who originally represented the Herald but now says he privately represents Kidwell, said in court on Monday the reporter is without support from his bosses and many of his colleagues.

Douglas Clifton, the Herald's executive editor, could not be reached for comment on Monday.

After several attempts to fight Kidwell's subpoenas to testify failed, the Herald's editors and attorneys told Kidwell to answer questions about the story because the case did not involve a confidential source or subpoenas of unpublished material, according to a story published in the Herald on Friday.

HERALD REPORTER GOES TO JAIL FOR SILENCE ABOUT ZILE STORY

Miami Herald, The (FL)

October 8, 1996

Author: MARTIN MERZER Herald Senior Writer

A Herald reporter who conducted a jailhouse interview with child-murder

suspect John Zile was himself jailed Monday after he refused to answer

lawyers' questions about his news-gathering efforts.

Circuit Judge Roger Colton of

West Palm Beach ruled that reporter David Kidwell, 35, was in contempt

of court. With little comment, the judge sentenced Kidwell to 70 days

in jail and a $500 fine.

``Mr. Kidwell,'' the judge said, ``good luck to you.''

With that, the reporter was fingerprinted and handcuffed. His pockets were emptied. His wedding ring was removed and given to his wife. A court officer escorted Kidwell to the Palm Beach County Detention Center, the same jail occupied by Zile.

Kidwell has been subpoenaed to testify at Zile's retrial, scheduled to begin Oct. 15 in Bartow. Zile is charged with first-degree murder in the October 1994 death of his 7-year-old step-daughter, Christina Holt.

During a pre-trial meeting with prosecutors last month, Kidwell refused to answer questions about an interview he conducted with Zile and the Herald story that resulted from that interview.

Prosecutors then filed the charge of indirect contempt of court, meaning that the alleged offense occurred outside the hearing of a judge.

In a statement to the judge Monday, Kidwell again defended his action as a matter of principle. Reporters, he said, should not testify about the interviews they conduct and the stories they write.

``I don't want to go to jail,'' Kidwell told Colton. ``I would rather go back to work this afternoon.

``But either way, when I do go back to work, I have to know I'm free to pursue all sides of a story without interference from the government, that I can represent myself as fair and impartial and know it's true.''

Prosecutors wanted Kidwell to verify the substance of his article, which included incriminating statements by Zile. They said Florida law required Kidwell to answer any and all questions about the story.

``David Kidwell is just a witness,'' prosecutor Scott Cupp told the judge. ``His statement about his professional convictions and ethics has nothing to do with this case. David Kidwell feels he is above the law.''

Said Kidwell: ``I know the law is against me.''

The Herald's attorneys and editors fought several unsuccessful legal battles on Kidwell's behalf, but ultimately advised him to answer questions about the interview and the story.

Newspapers frequently invoke constitutional freedom-of-the-press privileges when reporters are called to testify about their stories. Several courts ruled against The Herald in this case, the newspaper said, so Kidwell was now legally obligated to cooperate.

``It's an awful thing,'' said Herald Executive Editor Doug Clifton. ``I feel deep sympathy for him and for the position he's taken.

``But we have exhausted every remedy. We fought it vigorously in the courts and faced the unhappy conclusion that the law is not on our side.''

Clifton said The Herald would continue to pay Kidwell's salary during his jail term and fellow staffers were offering to pay the $500 fine.

Kidwell said prosecutors were interested in more than mere verification of his story. He said they sought unpublished information.

In any event, Kidwell said, any testimony related to his news-gathering techniques violated his professional ethics, and his conscience required resistance.

``Newspapers should be fair and independent and impartial,'' Kidwell said before Monday's hearing. ``At the point where I'm taking the stand for the prosecution, I'm not independent anymore. I'm not impartial. I'm being used as an agent of the police.''

The case spotlighted a murky, evolving branch of the law.

Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia have so-called ``shield laws'' that specify when reporters are protected from subpoenas. Florida has no such law, forcing reporters and their lawyers to rely on various interpretations of the First Amendment guarantee of a free press.

Some recent decisions in the state suggest that reporters who are not protecting a confidential source can be compelled to testify -- just like any other citizen. Some uncertainty even exists concerning reporters who are protecting sources.

In 1993, a reporter was sentenced to 30 days in jail for refusing to disclose the source of a story written for The Stuart News.

Until Monday, no other Florida reporter had ever been jailed for refusing to answer questions about the news-gathering process, though a rising number of Florida reporters have been subpoenaed to testify in criminal cases recently.

``Reporters like David Kidwell are going to find themselves either censoring themselves when they write pieces or simply becoming unpaid investigators for the state and the defense,'' said Kidwell's lawyer, Sanford Bohrer of Miami.

Bohrer represented The Herald in the case and now represents Kidwell privately, though The Herald has paid all of Kidwell's legal expenses.

Cupp, the prosecutor, said the law was clear and Kidwell had to testify or face the consequences. Cupp recited a list of other witnesses in the Zile case who were reluctant to testify and would be encouraged to resist if Kidwell was not sent to jail.

In response, Bohrer compared Kidwell to Henry David Thoreau, Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, all of whom resisted laws they believed were unjust.

``He's not just a witness,'' Bohrer said, ``and he's not a criminal. He's a person who saw injustice, and he sees this as the only way he can make his statement.''

The case that sparked this controversy already has received wide publicity.

Zile, 34, was charged with murder after he led police to Christina's body, buried behind a Kmart in Tequesta.

The development came about a week after Zile and his wife, Pauline, reported that Christina was missing. Pauline Zile, ultimately convicted of first-degree murder, is serving a life term in prison.

Kidwell interviewed John Zile shortly after Zile's arrest in November 1994. The reporter quoted Zile as saying he was ``furious'' with the girl, that he ``popped her on the mouth,'' spanked her until ``her butt was black and blue'' and buried her behind the Kmart.

Though Zile made similar statements to police, the newspaper report contained more details of his version of events. The story itself can be placed into evidence, Bohrer said, but prosecutors insisted that they needed Kidwell to testify about the story.

Zile's attorneys indicated that, if Kidwell testified, they would question his credibility. They said he deceived jail officials and Zile -- claims that Kidwell and his editors at The Herald denied.

The newspaper's attorneys initially sought to quash subpoenas served on Kidwell. They said a reporter enjoys constitutional protection from such subpoenas, particularly when alternate sources exist for any information the reporter can provide.

But after several legal defeats, including a rebuff by an appeals court on Aug. 19, Kidwell's editors advised him to cooperate with prosecutors and defense lawyers involved in the case.

``As an institution,'' Clifton said, ``we believe in the power of the law.''

Kidwell has worked at The Herald since 1990 and currently is assigned to its Fort Lauderdale office. He also has worked as a reporter for The Tampa Tribune, The Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville and several other newspapers.

He is married and has a 19-month-old son.

Zile's first trial, in West Palm Beach, ended in May with a deadlocked jury. The retrial was moved to Bartow, about 30 miles east of Tampa.

But those proceedings were suddenly suspended in August when Colton ruled that a court clerk in Bartow made inappropriate comments that tainted the entire jury pool. Though procedural delays are possible, the retrial is expected to begin again next week.

On Monday, the judge offered to release Kidwell from jail if he answers prosecutors' questions by Sunday, but Kidwell showed no sign of changing his mind.

``You can't go to jail and then back down,'' he said. ``I hoped that my willingness to go to jail would be enough to keep me off the stand. I hoped that cooler heads would prevail.''

JOURNALISTS' GROUP CONDEMNS JAILING OF HERALD REPORTER

Miami Herald, The (FL)

October 9, 1996

Author: MARTIN MERZER Herald Senior Writer

The nation's largest association of journalists on Tuesday condemned

the jailing of a Herald reporter who refused to testify about his interview

with a murder suspect.

A Palm Beach County circuit judge

ruled Monday that reporter David Kidwell was in contempt of court for

refusing to answer questions about his jail-house interview with accused

child killer John Zile. Kidwell was sentenced to 70 days in the Palm

Beach County Detention Center.

The Society of Professional Journalists called the sentence ``unduly

harsh'' and called for the reporter's immediate release. Kidwell's lawyer

has filed an appeal.

``If the public believes that reporters can be compelled to testify in such cases, it will significantly erode the credibility of the press,'' said Steve Geimann, president of the SPJ, which represents 13,500 journalists.

During a November 1994 interview with Kidwell, Zile provided details of his role in the death of his 7-year-old stepdaughter, Christina Holt. Charged with first-degree murder, Zile faces trial next week.

Prosecutors want Kidwell to verify the accuracy of the story he wrote and answer questions about it. Kidwell refused, saying that such testimony would compromise the independence of journalists.

Geimann supported Kidwell's stand.

``Prosecutors have paid staffs to investigate murder cases,'' Geimann said. ``They shouldn't compel reporters to do such work. We can't and we shouldn't become extensions of the prosecutor's office or the police or any other government agency.''

Kidwell's wife, Pat Dunnigan, said he was ``doing pretty well'' in jail, sharing a dormitory cell with 50 other prisoners.

``I think he's still a little shellshocked,'' she said. ``I don't think he expected the sentence to be this long, but he's not even considering testifying in the case.''

SAVE THE PROSECUTIONS FOR CROOKS, NOT PRESS

The Palm Beach Post

October 10, 1996

Because he is running for reelection, Palm Beach County State Attorney

Barry Krischer talks about all the people his office has sent to jail.

In prosecuting David Kidwell, however, Mr. Krischer went too far.

Mr. Kidwell is a reporter for

The Miami Herald. In 1994, he interviewed John Zile in the county jail.

Zile had just been arrested in the death of his stepdaughter, 7-year-old

Christina Holt. Mr. Kidwell didn't tell anyone at the jail that he was

a reporter; he said was a friend of Zile's. During the interview, Zile

talked about his role in the murder.

Prosecutors sometimes show mild interest in news stories about crimes,

but usually they're able to gather the evidence on their own. Since

Zile had confessed to police investigators, no one in Mr. Krischer's

office thought Mr. Kidwell's interview was important - until the trial

ended with a hung jury.

At that point, perhaps because Mr. Krischer worried about losing the retrial of this high-profile case during an election year, prosecutors became interested. They subpoenaed Mr. Kidwell, even though his testimony would have been redundant. Mr. Kidwell refused to testify. The Herald asked Circuit Judge Roger Colton to quash the subpoena. He refused, and the 4th District Court of Appeal backed him up.

So on Monday, Judge Colton sentenced Mr. Kidwell to 70 days in jail for contempt of court. He should have drop-kicked Mr. Krischer's subpoena and told him to reread the First Amendment. The public may be justifiably irritated by what some reporters do, and reporters give reason for the public to be irritated more often than they should. But making reporters work for the state is a serious threat to the public's ability to get information, not just an irritant.

Zile's alleged crime was heinous. He escaped conviction when one juror held out, saying she could not convict Zile of first-degree murder, the verdict favored by the other 11 jurors. Mr. Krischer and his prosecutors, like everyone else, want justice for the tragedy that befell a little girl. Their cause, however, doesn't justify their actions, especially when they didn't need the testimony to make their case.

Mr. Kidwell acted unprofessionally by misrepresenting himself. That lapse, however, doesn't make him a criminal. Nor do they give the state attorney's office an excuse to shake down a reporter for information that's available for 50 cents. Fundamental rights, such as press freedom, aren't granted selectively. The right is always defensible even if the individual isn't.

A CASE OF ETHICS VS. PURSUIT OF

JUSTICE

Sun-Sentinel

October 11, 1996

Author: JOHN GROGAN

A newspaper reporter went to jail this week rather than answer questions

in the criminal trial of South Florida's most notorious stepfather,

accused murderer John Zile.

Nearly every non-journalist I

have spoken to has responded the same way: "What's this guy's problem?"

The public seems to have little sympathy for members of the media who

defy the authorities in the name of journalistic ethics.

David Kidwell, a reporter for The Miami Herald, was jailed on Monday for refusing to testify about incriminating statements made by Zile to him during a jailhouse interview.

For journalists, the Florida case law that compelled Kidwell to choose the witness chair or a jail cell is a chilling reminder of the fragility of a press independent of government. But this case, the horrific murder of a defenseless child at her own parents' hands, has raised the stakes. Even many staunch defenders of the First Amendment are wondering if Kidwell picked the right battle.

It's not as if Kidwell is fighting to protect the identity of a confidential source, a sacred privilege most of us can appreciate. Prosecutors say they merely want him to confirm incriminating statements made by Zile. Those statements are no secret: they were splashed across the next day's front page.

So what's the harm if it can help jurors reach a just verdict?

One issue is what the reporter chose not to put in the story. Once he took the stand, prosecutors could ask him to divulge everything he knew. And defense lawyers would likely try to discredit him by impugning his professional abilities - something that could have a chilling effect on future reporters considering whether to cover similar stories.

On the other side is the speculation that Kidwell may be less concerned with an unfettered press than with the notoriety of being a celebrated martyr among his colleagues.

Zile is charged with beating to death his stepdaughter, Christina Holt, 7, and burying her body behind a Kmart in Tequesta. An earlier jury deadlocked over his guilt.

In defense of a free press

Kidwell and his lawyers fought the subpoena and lost. They appealed and lost. His bosses advised him to cooperate. Still he refused. It begs the question: Once a citizen exhausts his legal remedies, is he still justified in disobeying the law? What if everyone did that?

Complicating the matter was the questionable way in which Kidwell landed the exclusive interview.

According to Zile's lawyers, he lied to guards at the Palm Beach County Jail, misrepresenting himself as a personal friend.

Are journalists above the law? I called Kidwell's attorney, Sandy Bohrer, to explain.

"The way the American system of justice works requires that the press be outside the system looking in," Bohrer said. "That's why we have the freest press in the world and the [longest standing) democracy in the world."

Faced with the possibility of a court subpoena every time they gather information, reporters will begin to curb their curiosity, Bohrer said.

"Where do you draw the line?" he asked. "How do we draw the line? The reporter is not there to gather information for the government."

He differentiates between a reporter who happens to witness a murder on his way to work and a reporter who, responding to a tip, arrives with notebook in hand and witnesses the same murder. The first, he says, has an obligation to testify; the second does not.

I agree the separation of the media from the state is as sacred as the separation of church and state. I understand the death of a free press can occur not only by a dictator's edict but by slow erosion, one case at a time.

But a small girl is dead without ever having had a chance at life. If there is a case where journalistic freedoms should take a back seat to the pursuit of justice, perhaps this is it.

Kidwell the journalist has no obligation to help see justice done. What about Kidwell the citizen?

John Grogan's column appears every Sunday, Wednesday and Friday.

LESSON BEING LOST: JOURNALISTS SERVE PUBLIC INTEREST, NOT GOVERNMENT'S

Sun-Sentinel

October 13, 1996

Author: EARL MAUCKER

Editor

If you want to be a journalist in Venezuela, you have to get a license

from the government.

And that's not the only country

where the powers that be try to control the media. At the 52nd General

Assembly of the Inter-American Press Association this week in Los Angeles,

I heard of dozens of cases throughout the Americas where threats against

journalists continue.

Licensing laws like Venezuela's are pending in Nicaragua and Chile.

Pressure by police and government officials is a constant threat in Haiti.

In Mexico, intimidation, kidnapping, lawsuits and physical attacks against journalists are common.

In Argentina, journalists are subjected to threats and intimidation.

In Florida, a reporter is serving time in jail right now because he refused to be treated like an arm of the police force.

Whoa! Back up.

Florida?

Florida, U.S.A?

The case involves Miami Herald reporter David Kidwell, 35, who was ordered jailed for 70 days for refusing to testify in the trial of John Zile, accused of killing his 7-year-old stepdaughter.

Prosecutors want Kidwell to testify about his jailhouse interview with Zile.

Kidwell's case may not be the perfect one for arguing that the courts have gone too far. There is some question of whether he misrepresented himself as a friend of Zile's to get the interview. And even his newspaper thought that, once the legal appeals were exhausted, Kidwell should agree to testify.

But there is principle here that should not be lost, despite some of the background of this particular case: Journalists serve the public, not the government. They shouldn't be thrown in jail for doing their job.

But, increasingly, the courts have attempted to pull journalists into the system to act as witnesses, and in Florida there have been three recent cases that have undermined protection for reporters.

Of course, in tragic cases like the murder of a child, it is natural for most people to side with the courts.

None of us - including journalists - wants to see the killer of Christina Holt go free because the state was unable to get the evidence it needed.

But in most cases the prosecutors have means of gathering information other than disregarding the First Amendment. And that's so in the Zile case. Prosecutors already have their own interview with Zile. It might be nice, from their point of view, to also be able to ask the reporter what Zile said, but that nicety is not worth the damage being done to a free press.

On Thursday, reporter Michelle Worobec was ordered to appear this week in court to testify in the trial of a defendant in the Cracker Barrel triple murder case in Naples. Worobec, 32, covered the story for the Naples Daily News.

In June, a freelance reporter for XS magazine was compelled to discuss with prosecutors his interview with an accused murderer. Newspaper attorneys argued that the reporter was entitled to protection under the qualified journalist privilege, noting he was not a witness to a relevent event.

In that case, the court ruled that the journalistic privilege applied only in cases involving confidential sources.

Basically, that decision allows any lawyer to subpoena any reporter covering any news story.

A lawyer friend told me after tha ruling that, as far as he was concerned, he had a newsroom of private investigators in any traffic case that may come his way.

While his comments were somewhat in jest, his point was well taken. When the atmosphere develops where it is common practice for reporters to be used as witnesses, people will be increasingly reluctant to talk freely. That's one definition of an oppressed society.

When handcuffed and led off to jail, Kidwell made remarks eriely familiar to comments heard by journalists during the convention:

". . . I have to know I'm free to pursue all sides of a story without interference from the government," he said. "At the point I'm taking the stand for the prosecution, I'm not independent anymore. I am not impartial. I'm being used as an agent of the police."

Very scary.

BLAME FOR MISTRIALS? JURY OUT

ZILE RETRIAL TO BEGIN IN BARTOW

Sun-Sentinel

October 13, 1996

Author: STEPHANIE SMITH Staff Writer

Staff Writer Mike Folks contributed to this report.

The Palm Beach County State Attorney's Office returns to Bartow on Tuesday

to pick another jury in the murder retrial of John Zile.

The state's attempt to convict Zile of first-degree murder and aggravated child abuse of his stepdaughter Christina Holt, 7, has misfired twice.

On May 16, a jury deadlocked 11-1

on a guilty conviction in the case that first drew public attention

in 1994 when Zile and his wife, Pauline Zile, tried to cover up the

child's death by claiming that Christina had been abducted.

In August, John Zile's second trial ended when a week of jury selection

was dumped because the jury pool was tainted by remarks made by Polk

County's clerk of courts.

While her husband awaits trial, Pauline Zile, 25, is serving a life sentence since last year for first-degree murder and aggravated child abuse. She was convicted of murder because she did not step in when her husband allegedly beat the child and the girl died.

Last month, the Neal Evans first-degree murder case ended in mistrial when jurors deadlocked 10-2.

Evans was accused of killing an Atlanta Braves replacement pitcher during a botched robbery attempt outside the player's West Palm Beach hotel during spring training last year. Evans is black; the two jurors who voted to acquit him were black.

In between Zile and Evans, hung juries produced three other mistrials:

-- A June 26 mistrial in the armed robbery, carjacking and kidnapping case of Tim Rainey.

-- An Aug. 28 mistrial in the armed robbery and kidnapping trial of Keith Mason and the Aug. 31 mistrial in the aggravated battery trial of four teen-agers accused of beating high school junior Joseph Pymm into a monthlong coma.

The mistrials have many wondering who is to blame.

It can't be attributed to prosecutors, said Mike Edmondson, spokesman for State Attorney Barry Krischer, who faces re-election in November. There are too many factors, he said.

And even though Circuit Judge Roger B. Colton presided over all the mistrials except the Pymm case, he can't be blamed, observers say.

"I have no reason to believe that had those cases been heard by another judge with the same jury that a different verdict would have been reached," Palm Beach Circuit Court Chief Judge Richard Oftedal said.

"You've got a 12-person jury and you've got to get 12 people to reach a unanimous decision," Oftedal said. "I don't think there's any fault that can be attributed to the judge."

Colton declined to comment on the mistrials.

Nevertheless, the State Attorney's Office has heavily lobbied Oftedal to get Colton reassigned to civil cases after just one year on the criminal bench. Colton began his career on the civil side in 1994 after his election.

In the Evans case in September, the State Attorney's Office unsuccessfully demanded that the Fourth District Court of Appeal remove Colton as the trial judge.

During the same trial, the State Attorney's Office packed the courtroom gallery with its top prosecutors as a show of force when Colton was scheduled to make a ruling that could hurt the prosecution.

Whether the State Attorney's Office will get its way with Colton depends on Oftedal, who said Friday he is working on next year's judicial assignments. He declined comment on whether Colton will remain on the criminal bench.

Circuit judges often are put on rotation to different divisions such as civil, criminal, family and probate. The changes don't take effect until Jan. 1.

Many things can prevent a jury from reaching a unanimous verdict, said Robert Pugsley, a criminal law professor at the Southwestern University School of Law in Los Angeles. Obstacles can include skepticism about police evidence, weak prosecution theories or even a judge's demeanor and command of the courtroom.

During the O.J. Simpson trial, Judge Lance Ito routinely was criticized for his lack of control of his courtroom, Pugsley said. Still, the jury was able to reach a unanimous verdict to aquit Simpson.

"Possibly, jurors are not being made to understand in clear and firm terms that their obligation is to reach a clear verdict," Pugsley said, "that a mistrial is not the norm, it's an exception, that everybody involved, from the defendant to the prosecution to the taxpayers, wants a resolution."

Like Ito, Colton has a reputation for being nice.

"Colton and Hugh Lindsey are the best-liked judges," Palm Beach County Circuit Judge Marvin Mounts said. "Ask anybody in this courthouse."

Mounts, who recalls less than a handful of hung juries in his two decades as a criminal court judge, said mistrials are just a part of the judicial process.

"They come along, they just happen," Mounts said. "It's an imperfect system, I'm an imperfect human being."

$180,000 LATER, ZILE'S THIRD TRIAL TO OPEN

The Palm Beach Post

October 14, 1996

Author: VAL ELLICOTT

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

The protracted effort to convict John Zile of murder in the death of

his stepdaughter has so far cost Palm Beach County taxpayers more than

$180,000, more than half of that in fees for Zile's two attorneys.

On Tuesday, prosecutors and defense

attorneys will begin questioning potential jurors in Bartow in what

will be the third attempt to obtain a verdict in the case.

Zile's first trial in West Palm Beach ended in May with a hung jury.

In August, Circuit Judge Roger Colton scrapped jury selection at Zile's

second trial after a Polk County court official made inappropriate comments

to jury candidates.

The attorneys in the case suggested to Colton that he oversee jury orientation himself this time to make sure the selection process goes smoothly.

"I think both sides would agree that our goal is to bring this trial to a conclusion," prosecutor Scott Cupp said Saturday.

To date, the bill for Zile's court-appointed defense totals $182,416.61, and that doesn't include a substantial sum that defense attorney Craig Wilson says he is still owed.

In July, Wilson billed the county $112,360 for his work on Zile's case, but Assistant County Attorney Dan Hyndman challenged the bill, calling it excessive. Wilson agreed to take $50,000 in fees until the dispute is settled. Zile's other attorney, Ed O'Hara, has been paid $57,447 so far.

Zile, 34, faces the death penalty if convicted of killing his 7-year-old stepdaughter, Christina Holt, around midnight on Sept. 16, 1994, in the Ziles' Singer Island apartment. His trial, which was moved to Bartow because of pretrial publicity in Palm Beach County, is expected to last three to six weeks.

Prosecutors say Christina cried out when Zile began abusing her by slapping and spanking her and flicking her lips with his fingers. Zile covered Christina's mouth to stifle her cries and the girl asphyxiated, prosecutors told jurors at Zile's first trial.

"She is scared out of her mind. He doesn't console her - he beats her," Assistant State Attorney Mary Ann Duggan said in closing arguments at that trial, which ended in a mistrial because one juror refused to vote for a first-degree murder conviction.

The defense argument is that Christina died of a seizure or from Zile's frantic but uninformed efforts to resuscitate her after the seizure. A critical element of the defense's case is that Christina, while not "a bad little girl," was disturbed and difficult to control.

"This child was clearly a troubled child, and John didn't know how to deal with it," defense attorney Ed O'Hara told jurors at the first trial.

A major concern for the defense is that some members of the jury may still recall - with a sense of outrage - that, after secretly burying his stepdaughter behind a Kmart, Zile collaborated with his wife, Pauline Zile, Christina's mother, to concoct the ruse that Christina had been kidnapped from a flea market in Broward County.

Pauline Zile was convicted of first-degree murder in the case last year after jurors concluded that she failed to intervene to prevent Christina's death. She was sentenced to life in prison.

ZILE'S DEFENSE COSTS

%%

Expert witness fees $33,496.50

Deposition costs $9,504.03

Investigative costs $12,997.71

Travel expenses $4,971.15

Attorneys' fees paid to Craig Wilson $50,000.00

paid to Ed O'Hara $57,447.50

Other Costs* $13,999.72

TOTAL $182,416.61

NO CHANGE OF HEART FOR JAILED REPORTER

Miami Herald, The (FL)

October 14, 1996

Author: MARTIN MERZER Herald Senior Writer

A Herald reporter begins his second week in jail today, as the final

deadline for his cooperation in the state's case against murder suspect

John Zile expired without a change of heart or a word of testimony.

``This is it,'' reporter David

Kidwell said from the Palm Beach County Detention Center, where he is

serving a 70-day sentence. ``I'm not going to change my mind.''

Circuit Judge Roger Colton ruled last Monday that Kidwell, 35, was in

contempt of court for refusing to answer questions about his jailhouse

interview with Zile, charged with first-degree murder in the death of

his 7-year-old stepdaughter, Christina Holt.

The judge offered to free Kidwell if he responded to prosecutors' questions by Sunday, but the deadline passed uneventfully.

Zile's first trial in West Palm Beach ended in May with a deadlocked jury. His retrial is scheduled to begin Tuesday in Bartow.

During a November 1994 interview with Kidwell, Zile said he was ``furious'' with Christina, and Zile provided details of his role in her death.

Though Zile made similar statements to police, prosecutors want Kidwell to verify incriminating details of the story and answer questions about it. Kidwell refused, saying that such testimony would compromise the independence of journalists.

Last week, another Florida reporter, Michelle Worobec of The Naples Daily News, was subpoenaed to testify under similar circumstances in a different case. She said she also would refuse.

Several journalism groups have praised Kidwell's stand, condemned his sentence as overly harsh and called for his immediate release.

``My feelings haven't changed,'' Kidwell said. ``The attorneys are doing what they can to make sure I don't set any records in here. I don't want to set any records in here.''

HRS WILL LOSE DISTRICT CHIEF AFTER NOV. 15

The Palm Beach Post

October 15, 1996

Author: BARBARA FEDER

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

The word had been buzzing around the state Department of Health and

Rehabilitative Services for weeks, but on Monday, local HRS chief Suzanne

Turner made it official:

After three years directing the

2,000-employee district office in Palm Beach County, Turner has resigned

to become "chief executive officer" for Home Safe, a local

nonprofit agency for abused children. Nov. 15 is her last day.

Turner, 53, will replace Home Safe Executive Director Mike VanWagoner

as the agency's top administrator, leaving VanWag-oner's future there

uncertain.

In her new job, which begins Nov. 18, Turner will be responsible for creating a "managed care" approach to helping abused and neglected children.

What that means: Right now, abused children are shuttled between hospitals, police stations, HRS and lawyers' offices to be examined and interviewed. Instead, Home Safe is building a "one stop" shelter where police, HRS investigators, doctors and others can interview children in a comforting, "kid-friendly" environment. The center, at John Prince Park, is scheduled to open in January.

Turner will also oversee what could be a radical restructuring in the way the county delivers services to abused children.

Instead of giving lump-sum payments to each agency that helps such children, Home Safe, HRS, the Children's Services Council, the Department of Juvenile Justice and other agencies have proposed putting that money into a "bank" in which dollars would "follow the child" for each service. They have applied for a $925,000 federal grant to start the "managed care" approach.

"It's an absolutely revolutionary situation," said trial attorney Robert Montgomery, Home Safe's board chairman, who cited Turner's "vast experience" with the county's child protective system as the reason Home Safe hired her.

Home Safe first offered the $100,000 position to former interim Hope House director Tom Watkins but was outbid by the Economic Council of Palm Beach County, a business lobbying group which Watkins now directs.

"I'm extremely excited," Turner said on Monday, noting that Home Safe's slightly more relaxed schedule will give her a chance to spend more time with her family in Indiana. "It's a challenge. The current system is dysfunctional."

Just how dysfunctional is something Turner, a former director of Indiana's Division of Family and Children, learned all too well. Just hearing the names A.J. Schwarz, Christina Holt and Pauline Cone still makes her wince.

What Turner says she learned, and will take to her new job: where the system's "shortcomings" - in money, people and training - lie.