Home --> Christina Holt's Story --> Christina Holt's Story: Newspaper Articles --> 1995 Page 9

Christina's Story

- Newspaper Articles

The following links take you to various articles in Christina's story

as it appeared in the South Florida media.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE INFORMATION ON THIS SITE BEFORE ASKING.

Thank you!

|

|

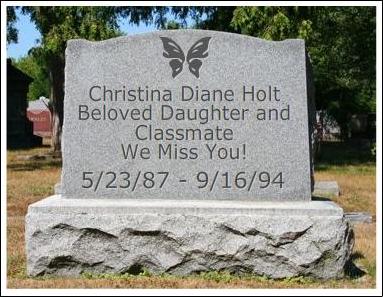

In Loving Memory Of May 23, 1987 - September 16, 1994 "Beautiful Child who has found love from the angels...RIP..." |

(Not her actual headstone) |

These

pages contain all of the articles from the Palm Beach Post and The

Sun-Sentinel throughout the years. |

|

Zile's Conviction

Bad News For Abuse-Case Attorneys (4/12/95)

Justice System Should Be Harsh To Florida's Murderous Mothers

(4/12/95)

1st-Degree Verdict Stuns Defendant Who Covered Up Child's

Slaying (4/12/95)

Zile's Performance Earns No Applause (4/12/95)

Jury: Mom A Murderer (4/12/95)

'My Wife Is Not a Murderer' (4/13/95)

Zile, Schwarz Child Death Cases Likely To Carry Same Penalties

(4/13/95)

Zile Blames Wife's Lawyers For Her Conviction (4/14/95)

Christina's Unnatural Mother (4/16/95)

Champion Of The Children (4/16/95)

ZILE'S CONVICTION

BAD NEWS FOR ABUSE-CASE ATTORNEYS

Sun-Sentinel

April 12, 1995

Author: STEPHANIE SMITH Staff Writer

Pauline Zile's conviction on Tuesday for first-degree murder was cause

for alarm for attorneys of other defendants charged with killing their

children but who have yet to go to trial.

Zile's may have been the weakest

in a series of child killing cases for the prosecution to get a first-degree

murder conviction because she was not directly involved in the killing

of her daughter, Christina Holt, 7.

Unlike her husband, the prosecution did not have a confession it could

use at trial. Unlike her husband, there was no evidence the woman laid

a hand on her daughter the night the child died.

"Is our case going to be more difficult? It will be infinitely more difficult," said Ed O'Hara, one of John Zile's attorneys.

John Zile faces trial in August.

Another concern is that attorneys in Pauline Zile's case went through 190 prospects before picking a 12-member jury, O'Hara said.

"If they didn't know about it before, everybody's heard of it now, after the notoriety surrounding the trial," O'Hara said.

On May 7, Paulette and Timothy Cone will be the next child killing case to go to trial in Palm Beach County.

Besides the Cones and John Zile, the others awaiting trial are Clover Boykin, accused of killing her son and a child she used to baby sit; Joanne Mejia, accused of shaking her baby son to death; and Jacqueline Caruncho, who is accused of shaking to death a child she was baby sitting.

Paulette Cone's attorney, Jack Goldberger, said on Tuesday he was worried there would be a spillover effect from Pauline Zile's trial.

"I'm very, very concerned that on the heels of Pauline Zile's case, we're going to trial," Goldberger said on Tuesday.

The Cones are charged with first-degree murder in the death of their adopted daughter, Pauline Cone, 2. The child died when a heavy plywood lid to her crib collapsed on top of her. Prosecutors say the child was kept in a cage.

JUSTICE SYSTEM SHOULD BE HARSH TO FLORIDA'S MURDEROUS MOTHERS

Sun-Sentinel

April 12, 1995

The two South Florida women whose names have become virtually synonymous

with the contemporary epidemic of criminally negligent parenthood both

experienced the wrath of an outraged society Tuesday.

Within the space of a few hours in separate Palm Beach County courtrooms, Pauline Zile and Jessica Schwarz were found guilty of murder in the deaths of their children.

A Circuit Court jury convicted Zile of first-degree murder and three counts of aggravated child abuse for failing to prevent last September's slaying of her 7-year-old daughter, Christina Holt.

Only hours earlier, Judge Karen L. Martin had found Jessica Schwarz guilty of second-degree murder in the 1993 drowning of her 10-year-old stepson, A.J.

Schwarz, who had waived her right to a second trial by jury, already is serving a 30-year sentence for a 1994 conviction of aggravated child abuse.

Zile faces the possibility of death in the electric chair in the sentencing phase of the trial before the same jury that convicted her.

Schwarz could be sentenced to life in prison in May.

Zile's husband John, who will be tried separately in August, also could be subject to the death penalty if he is convicted of first-degree murder in Christina's death.

The harsh judgments rendered and the severe penalties facing the two women accurately reflect the wave of public revulsion that swept South Florida after the shocking revelations of their lethal brand of mothering.

Zile made national headlines when she originally claimed that Christina had been abducted from a Broward County flea market, setting off an intense regional search for the little girl.

Within days, it was learned that Christina already had been dead for weeks, allegedly killed by her stepfather in a brutal disciplinary beating and buried behind a shopping center in northern Palm Beach County.

The mother, whose statements assisted police in solving the case, was charged with failing to stop the beating and participating in the attempted coverup.

The message of the Zile and Schwarz verdicts is clear: Their unthinkable acts constitute an affront to civilized society and the justice system is determined to offer them no more mercy than they granted to their innocent victims.

1ST-DEGREE VERDICT STUNS DEFENDANT

WHO COVERED UP CHILD'S SLAYING

Sun-Sentinel

April 12, 1995

Author: STEPHANIE SMITH Staff Writer

Staff Writers Jill Young Miller, Mike Folks, Cindy Elmore and Marego

Athans contributed to this report.

Pauline Zile, who seven months ago tried to convince South Floridians

that her child was abducted from a flea market, was convicted on Tuesday

of murder for failing to protect her daughter from being killed.

After 81/2 hours of deliberation

over two days, a Palm Beach County jury on Tuesday found Zile, 24, guilty

of first-degree murder and three counts of aggravated child abuse.

"Good! Good! Because she deserves it," said Brenda Money,

of Poolesville, Md., the great-aunt of Christina Holt, 7, Zile's dead

daughter.

Prosecutors said they would seek the death penalty at the sentencing hearing, which has not been scheduled. The same jury of nine men and three women will decide between life in prison or the death penalty, the only two options for a first-degree murder conviction.

Money, 28, whose own mother, Christina's great-grandmother, cared for Christina for five years, said Zile should pay for Christina's death with her own life.

"She didn't ask Christina if she wanted to live or die. It should be a life for a life," Money said.

After the trial clerk read the jury's verdict, Zile gasped, then lowered her head and cried. When she rose from the defense table, she propped herself up with both hands on the table. Then, she hung her head to cry again.

Zile was not prepared for a first-degree murder conviction, said Ellis Rubin, one of Zile's attorneys. The jury had a choice of lesser charges ranging from second-degree murder to manslaughter.

Rubin called the verdict an "outrageous miscarriage of justice."

He said the verdict was not about the death of Christina Holt but about punishing Zile for lying that Christina was kidnapped when the child had actually been dead for a month.

"I can't understand how those 12 good citizens swore to me under oath that they would not allow the fact that she lied to the public at the Swap Shop to affect their verdict.

"You tell me what evidence there was in this case of first-degree murder. There was none whatsoever. I am totally flabbergasted," Rubin said.

Child abuse prosecution experts say a first-degree murder conviction is difficult to get, even when the defendant directly caused the child's death.

Ryan Rainey, senior legal counsel with the National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse in Alexandria, Va., said too often, society dismisses child abuse as a family's method of discipline that got out of hand.

"We don't give the same benefit to children that we give to adults. Do we say when an adult is killed, `Well, he was obnoxious, so therefore it wasn't first-degree murder, it was discipline?'" Rainey said.

Zile's husband, John Zile, told police the death was an accident. He said he was disciplining his stepdaughter for playing doctor with her younger half brother and for telling lies.

When the child died, the Ziles hid the girl's body in a closet for four days instead of calling for help or police. John Zile told police he did not call for help because of bruises on the child's body from previous beatings.

He said he buried the body, covered with duct tape and five layers of blankets and tarps, in a vacant lot in Tequesta.

About a month later, he and his wife came up with a scheme to say Christina had been abducted from the Swap Shop near Fort Lauderdale in an effort to explain her disappearance.

John Zile's trial for first-degree murder and aggravated child abuse is scheduled for August.

During the seven days of testimony in Pauline Zile's trial, her attorneys argued she had nothing to do with the actual killing and could not be convicted of first-degree murder for her part in the abduction hoax.

But prosecutors Mary Ann Duggan and Scott Cupp contended that parents or guardians must act to protect their child from harm, and ignoring abuse of their child is criminal.

Zile did nothing, prosecutors argued to the jury, while her daughter was beaten by her husband. That made her just as guilty as if she had killed the child, prosecutors contended.

The prosecution's case tried to focus the jury's attention on the abduction hoax, saying it showed Pauline Zile was her husband's partner in the killing and cover-up.

The jury was shown a portion of Zile's tearful pleas on television for the return of her daughter.

Rubin said he does not regret his decision to not present a defense or let Zile testify. "There was no defense to put on because they had no evidence of first-degree murder," he said.

Rubin said Pauline Zile's conviction will not stand up on appeal.

But to those close to Christina, her mother's convictions fit the crime.

"Oh, yes! Oh, yes! Oh, yes! I'm so happy!" said Lisa Kelley, the fiancee of Christina's biological father, Frank Holt.

Kelley said she was shaking with excitement about the news.

"Frankie is going to be bouncing off the walls!" Kelly said. Frank Holt was not home and could not be reached despite repeated phone calls.

"It's finally over. Now we've got one more to go, and that's John. He's going to fry. If she fries, he'll fry," she said.

Christina had lived with her father's relatives in Maryland for most of her life. The couple divorced shortly after her birth.

For five years, she lived with Dorothy Money, the great-grandmother. Then Judy Holt, Christina's grandmother, took custody.

Last June, Holt decided the child belonged with her mother and brought her to Florida. Four months later, the child was dead.

The Ziles told friends Christina was used to being a spoiled, only child, and her sudden arrival in Florida when they already had two sons and were expecting a third child was too much of a strain on the family.

Brenda Money said Zile could have easily sent the child back if the situation was too much to bear.

Tuesday's verdict was judged fitting as well to the Broward County sheriff's officers who tried to find Christina after she was reported missing, only to learn she was already dead.

"All the investigators involved in the Christina Holt missing persons case are very pleased with the jury's verdict, and hopefully, everyone remembers the victim in this case. And that is Christina," said Detective Sgt. Dave Robshaw, who led the Broward County Sheriff's Office investigation into her disappearance.

Robshaw is reminded of Christina every day. A picture of the smiling, bright-eyed child sits on his office bookshelf, right next to the strikingly similar picture of his own 7-year-old daughter.

"I have the pictures here side by side," Robshaw said. "Everyone got close to Christina during the investigation."

ZILE'S PERFORMANCE EARNS NO APPLAUSE

Sun-Sentinel

April 12, 1995

Author: JOHN GROGAN Commentary

Pauline Zile, always quick with a sob and a bite of the lip, was a professional

at portraying herself as the wronged victim.

Sitting in the courtroom, so girlishly pretty in pastels and curled hair, she perfected the pained expression of a mother in mourning.

At her lawyer's side, she struck the proper dolorous pose, tears streaking her cheeks, the picture of victimhood.

Even before the truth came out,

as she faced television cameras to lie about the whereabouts of her

murdered daughter - cradling a doll we would only later learn was purchased

after the child's death as a sympathy prop - she evoked pity.

Pauline Zile, tragic heroine, powerless pawn to a diabolical husband.

In the end, the jury did not buy it.

Zile wanted jurors to find her as much a victim as her dead daughter, Christina Holt. She wanted them to feel her pain and forgive her weakness.

But they saw her for what she is: a shrewd and calculating manipulator capable of lying so convincingly she almost fooled the nation into thinking her daughter was the victim of a random kidnapping.

Tears aside, one cool accomplice

What the jury could not ignore was that, for all her command-performance sniveling, Pauline Zile watched her child's murder and then coolly plotted to explain it away.

She slept in the same room with the rotting corpse and took her sons along to buy the shovel and tarp to bury it.

In convicting her on Tuesday of first-degree murder and aggravated child abuse, the jury sent a message that it won't be swayed by cheap theatrics. A judge in another courtroom at the Palm Beach County Courthouse on the same day sent a similar message to another paragon of motherhood, Jessica Schwarz, convicting her of second-degree murder in the death of her stepson, A.J., whose nude and battered body was found floating in the family swimming pool west of Lantana.

These were not just messages to the two women involved but to all parents that a child's life is worth protecting.

As a young mother said to me after the verdicts were announced, "I can't understand what happened to the maternal instinct."

Any dog would fight for her pups, she said.

The missing will to protect

Remember Sheba the mother dog in Oakland Park that broke free from her chain to dig up her nine newborn pups her owner had just buried alive? If only Pauline Zile had shared that determination to protect. Instead she helped bury her 7-year-old in a sandy pit behind a Kmart.

Pauline Zile may not have dealt the fatal blow - her husband, John, awaits trial on that count - but she stood by silently as the abuse escalated to a final beating so severe it sent her daughter into fatal convulsions.

Was a first-degree murder conviction too harsh? Has Zile suffered enough already? I've heard many say they think so.

When I think of suffering enough, I don't think of Zile. I think of Christina Holt, shuffled from relatives in Maryland to live with her absentee mother in June and dead by September. Three months and no chance.

Clearly, Zile does not deserve to be put to death. But she is no wronged innocent, either.

Even if not brave enough to step between her husband and her daughter, she could have dialed 911 as her daughter convulsed on the floor. She could have fled with the children at the first signs of abuse. At the very least, she could have told the truth when police began asking questions.

Instead she put on her most fragile face and set out to remake herself as the real victim of this tragedy.

Suffered enough?

We are left with only one question: Whatever happened to the maternal instinct?

John Grogan's column appears every Sunday, Wednesday and Friday.

JURY: MOM A MURDERER

PAULINE ZILE GUILTY IN FIRST DEGREE

Miami Herald, The (FL)

April 12, 1995

Author: LORI ROZSA Herald Staff Writer

Pauline Zile -- a white, girlish bow in her hair contradicting the fiendish

portrait sketched of her as wicked mother and liar -- trembled and wept

Tuesday as she heard the worst:

A Palm Beach County jury found her guilty of murder in the first degree

for sitting by and letting her angry husband flail to death her 7-year-old

daughter Christina Holt, who had lived with the couple for three hellish

months.

Jurors added guilty verdicts on child abuse charges for Zile's slapping the girl on three occasions. The prosecution is seeking the death penalty.

The case first galvanized South

Florida when a tearful Zile

went on TV pleading that her daughter had been kidnapped from the Fort

Lauderdale Swap Shop. Within a week, she admitted the girl had been

beaten and buried in a shallow grave behind a Kmart. The story -- rife

with contradictions -- was a cover-up.

The first-degree verdict was a surprise to some, because Zile, 25, did not administer the actual blows that killed the girl. Coming after jurors viewed gruesome photographs of the girl's body after it was disinterred, it indicates the problems the defense faces in the upcoming trial of her husband, John Zile.

He will stand trial in August on the same charges and is likely to face similar damning testimony about his cruel treatment of the child. Prosecutors said he beat her, tortured her, even dropped her off on a street corner in a dangerous part of town one night to teach her a lesson about running away.

While jurors and others in the courtroom winced and sobbed at evidence and testimony during the trial, Zile remained stoic and controlled, except for weepy spells when videotapes of her televised pleas were shown or when the death penalty was mentioned.

But when the verdict was read, it was her turn. She convulsed and tears ran from her eyes.

She watched the 12 solemn jurors -- nine men and three women -- file out in front of her. None turned to look at her, though they passed just three feet away.

"She's in terror," said Ellis Rubin, one of her attorneys, when asked how his client took the news.

Rubin said the state, the public, and the jury are more interested in retribution than justice because Zile "scammed them" with the hoax.

Barry Krischer, Palm Beach County state attorney, disagreed.

"The fact is, there's a little child dead and buried," Krischer said.

Christina was "an inconvenience" to the Ziles, assistant state attorney Mary Ann Duggan told jurors in her closing arguments. "This precious little girl was in their way."

Maintaining his outrage, Rubin said the conviction should frighten parents.

"Every parent in Palm Beach County is in danger because Pauline Zile today was convicted of aggravated child abuse . . . for nothing more than what a neighbor said she heard was two slaps," Rubin said. "I am totally shocked. This is the worst miscarriage of justice I have ever seen in 45 years as an attorney."

Christina spent most of her life with relatives in Maryland. She came to live with her mother and Zile and their two young sons in their tiny Singer Island apartment in June; 90 days later, she was dead.

Duggan said Christina's three months "in that horrendous household" included regular beatings and humiliation, like the time her stepfather made her pull down her pants to show one of his friends where he'd beaten her. Zile then whipped her with a belt in front of the man.

Duggan described how Christina, even in such a short time, "was destroyed by the Ziles." She spent only five days in school before her mother pulled her out. She was hugging and clinging to her teacher and didn't want to leave.

"She was a prisoner in that dark, horrible, small place. She was isolated and in pain," Duggan said. "She had absolutely no hope. She had no one to turn to . . . her spirit was broken."

Her half-brothers, Daniel, 5, and Chad, 3, sometimes tried to come to her rescue. Duggan said during one beating, the boys banged on the door demanding to know what was going on. Pauline told them not to bother their father, Duggan said.

"Pauline Zile had a duty to stop it," Duggan said, "but she didn't." During closing arguments, Zile held in her lap a photo of the two boys, who were taken from her after her arrest.

Her husband, in an interview with The Herald soon after his arrest, said Pauline "smacked" Christina "a couple of times" the night of her death, Sept. 16, after she had soiled her pants.

He said he "popped her in the mouth" and spanked her, but didn't hit her hard enough to kill her. She began choking on her own vomit, he said, had a seizure, and died.

The Ziles wrapped Christina's body in a sheet and stuffed it into a closet for four days. Then they wrapped her in a tarp and buried her in an empty lot behind the Kmart in Tequesta.

After police began suspecting the Ziles, John Zile said he and Pauline wrote out suicide notes, then drank a bottle of Jim Beam and bottle of NyQuil. They sat in their old Cadillac waiting for the carbon monoxide fumes to kill them. The car ran out of gas.

The jury will vote on whether to send Pauline Zile the electric chair after a sentencing hearing, which hasn't been scheduled.

`MY WIFE IS NOT A MURDERER'

The Palm Beach Post

April 13, 1995

Author: CHRISTINE STAPLETON

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Pauline Zile, convicted of first-degree murder Tuesday for her daughter's

death, got some good news Wednesday when experts recommended to a judge

that she and her husband be allowed to visit their young sons.

``I feel sorry for my wife,''

John Zile said as he was escorted into the private hearing on Wednesday.

``I just want to say that Ellis Rubin is the most incompetent lawyer

I've ever seen. . . . Her convictions will be overturned on appeal.''

Rubin, one of Pauline Zile's attorneys, said that ``any criticism from

John Zile is the greatest praise anyone can ever get.''

``He's charged with killing his stepdaughter and he's attempting to kill Pauline and now he wants to kill my reputation,'' Rubin said. ``He's stepping along right in stride, killing everything he touches.''

But Zile, whose first-degree murder trial is scheduled to begin in August, was adamant in his support of his wife on Wednesday. Holding his head high, Zile said: ``My wife is not a murderer.''

The couple, handcuffed and escorted separately to court, have fought the efforts of the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services to terminate their parental rights.

HRS took custody of Daniel, 5, and Chad, 3, when their parents were arrested nearly six months ago. Since then, they have lived with a foster family and have not been allowed to see or speak to their parents.

Until recently, HRS officials refused to give the couple the boys' report cards, school records or recent photographs of them. Circuit Judge Richard Burk listened to more than 40 minutes of testimony from a child psychologist but did not rule on whether the couple could see their sons.

Still unresolved is whether the couple will be allowed to have a contact visit with the boys. Timothy and Paulette Cone, also charged with first-degree murder in the death of their adopted daughter, won a similar court battle and have been allowed regular contact visits at the jail with their young son.

``Obviously they miss their children and love their children very dearly,'' said Ed O'Hara, one of Zile's attorneys. Zile was ``disappointed'' with the jury's verdict on Tuesday because ``he had hoped for a reunification of the boys with Pauline'' if she had been found not guilty, O'Hara said.

In statements to police, he said his 7-year-old stepdaughter, Christina Holt, died after he hit her and she went into convulsions Sept. 16. The couple tried to revive the girl in the bathtub, then hid her body in a closet in the family's one-bedroom apartment on Singer Island.

Zile said he buried the girl four days later behind a shopping center in Tequesta. To cover up her death, they staged a kidnapping hoax a month later at the Thunderbird Swap Shop in Broward County.

ZILE, SCHWARZ CHILD DEATH CASES

LIKELY TO CARRY SAME PENALTIES

Sun-Sentinel

April 13, 1995

Author: STEPHANIE SMITH and MIKE FOLKS Staff Writers

Pauline Zile stood idly by during the beating of her daughter that ended

the child's life, and now she faces the death penalty after her first-degree

murder conviction on Tuesday.

Jessica Schwarz relentlessly tortured

her stepson for two years until she drowned him by knocking him unconscious

or holding him under water. She faces a maximum of life in prison after

her second-degree murder conviction on the same day.

Two mothers, two children dead, two different charges and convictions.

Assistant State Attorney Scott Cupp, head of the crimes against children unit, presented both cases before grand juries and prosecuted both women. While the charges and convictions are different, the punishment will most likely be the same, Cupp said on Wednesday.

"What people don't seem to understand is they're both going to be serving life in prison," he said.

Still, why was Schwarz indicted for second-degree murder while Zile was charged with first-degree murder?

"Everybody believes the State Attorney's Office controls grand juries, but grand juries come back with higher or lower charges than what you asked for, and you don't know why they do what they do because it's all secret," Cupp said.

Schwarz's attorney, Rendell Brown, doesn't believe that. Prosecutors always push for the highest charge they can get with a grand jury, Brown said on Wednesday.

"They had no evidence of anything, but they had a dead child," Brown said of the death of A.J. Schwarz, 10, on May 2, 1993.

"If [prosecutors) believed what she was convicted of, the grand jury would have come back with first-degree murder," Brown said.

The major obstacle for the prosecution in A.J.'s death was the autopsy. Palm Beach County Medical Examiner James Benz said he could not be certain the boy's death was a homicide. Without a homicide, how can you have a murder? Brown argued in court.

"We went into that with the chief medical examiner in Palm Beach County as a defense witness," Cupp said.

Cupp got a second opinion from a medical examiner from Atlanta, who testified he could not scientifically attest the death was a homicide, but his personal thoughts were that it was. More than 30 bruises covered A.J.'s body, and he was found drowned in a waist-high, above-ground swimming pool.

Then comes the next question: Why was A.J.'s biological father David "Bear" Schwarz not criminally charged for his failure to protect his son, as Zile was in the death of her daughter, Christina Holt, 7?

"Bear was never there," Cupp said of the long-haul truck driver. "That would have been a difficult case as a test case because everybody agreed Bear wasn't around and he didn't know. Some witnesses indicated he didn't seem to want to know, but saying he should have known and proving that he did know are two different things."

Also, the father may have had a legitimate battered spouse defense, because police reports indicated his wife attacked him, Cupp said.

The first-degree murder conviction of Zile may be a legal landmark, said Ryan Rainey, senior attorney for the National Center for the Prosecution of Child Abuse in Alexandria, Va.

"I don't think it's happened before, a conviction for first-degree murder for omission, failing to act," Rainey said. "I think this is the test case that's been building up for the last couple of years. The facts were heinous enough to reach that threshold with a jury for a murder conviction."

The laws to find parents or guardians criminally responsible for not protecting their children have been around for years, Rainey said, but prosecutors who have tried to use them have been mostly unsuccessful in getting convictions.

John Zile, who will go to trial in August, said on Wednesday his wife should not have been found guilty of murder.

"My wife is not a murderer," he said outside a hearing to decide visitation with their two remaining children, Daniel, 6, and Chad, 3, who are in state custody.

"She just had a bad lawyer. I feel sorry for my wife. She will win on appeal," he said.

ZILE BLAMES WIFE'S LAWYERS FOR

HER CONVICTION

Miami Herald, The (FL)

April 14, 1995

Author: Associated Press

John Zile, accused of fatally beating his 7-year-old stepdaughter, said

his wife isn't a murderer and blamed her lawyers for her murder conviction.

Pauline Zile, 24, could face the death penalty after being found guilty

earlier this week in West Palm Beach of standing by while Christina

Holt was beaten. She and her husband had concocted an abduction tale

to cover up the girl's death.

"Any condemnation from John Zile is the highest compliment I have ever been paid," Ellis Rubin, one of Pauline Zile's attorneys, said Thursday.

John Zile is to go on trial in August on the same charges as his wife. He also would face the death penalty, if convicted.

"He's charged with killing his stepdaughter, and he's attempting to kill Pauline, and now he wants to kill my reputation," Rubin said. "He's stepping along right in stride, killing everything he touches."

On his way to a private hearing Wednesday, John Zile said he felt sorry for his wife.

"I just want to say that Ellis Rubin is the most incompetent lawyer I've ever seen," he said, predicting her convictions will be overturned on appeal. "My wife is not a murderer."

Pauline Zile's attorneys had rested their case without putting her on the stand or offering any testimony. They said the prosecution had presented no evidence against her and blamed intense publicity for her convictions.

Rubin said Thursday that Pauline Zile was holding up as well as can be expected.

"She faces each night and day in terror," he said. "She faces the electric chair, which is so outrageous and incredible that I will do everything to prevent that from becoming a possibility."

On Wednesday, the couple got some good news when experts recommended to a judge they be allowed to visit their young sons.

The couple, handcuffed and escorted separately to court, have fought the efforts of the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services to terminate their parental rights.

HRS took custody of Daniel, 5, and Chad, 3, when their parents were arrested nearly six months ago. Since then, they have lived with a foster family and have not been allowed to see or speak to their parents.

Until recently, HRS officials refused to give the couple the boys' report cards, school records or recent photographs of them. Circuit Judge Richard Burk listened to testimony from a child psychologist but did not rule on whether the couple could see their sons.

"Obviously, they miss their children and love their children very dearly," said Ed O'Hara, one of Zile's attorneys. Zile was disappointed with the jury's verdict on Tuesday because "he had hoped for a reunification of the boys with Pauline" if she had been found innocent, O'Hara said.

In statements to police, Zile said Christina died accidentally Sept. 16 after he hit her for soiling her pants.

The couple staged a televised hoax a month later, saying Christina had been kidnapped from a popular flea market in Broward County.

The fake abduction drew national attention just a week before a South Carolina mother claimed her two sons had been abducted by a carjacker. Susan Smith later admitted to drowning her sons in her car in a lake, authorities say.

CHRISTINA'S UNNATURAL MOTHER

The Palm Beach Post

April 16, 1995

Author: RANDY SCHULTZ

Minutes before lawyers were to resume arguing over whether she would

face the electric chair for doing nothing to keep her husband from murdering

her daughter, Pauline Zile leaned over and showed something to her attorney.

It was a photograph of her two sons.

Zile did not make the gesture

to gain favor with the jurors. They weren't back in the courtroom after

the Monday lunch break. She looked for all the world like a mother who

had been on vacation and was eager to get back to her kids. Just a little

bit longer, and life would be back to normal.

Throughout her trial, which ended Tuesday, Pauline Zile watched the

proceedings with fascination, seemingly enthralled with being the center

of attention. Dubbed ``Princess Pauline'' by guards at the county jail

for the fuss she made over herself before going to court - fixing her

hair, choosing just the right dress - Zile approached this fight for

her life with a sense of unreality.

Only when the jury came back for the last time did she come apart, sobbing as the four verdicts were read: first-degree murder - guilty; aggravated child abuse - guilty; aggravated child abuse - guilty; aggravated child abuse - guilty. Suddenly, she wasn't an actress, and it wasn't a TV show. She would not be going home to her sons.

Natural mother vs. stepmother

There is a darkly surreal aspect to any trial in which a parent is charged in the killing of his or her child. That mood was heightened on Tuesday because two women had their day of reckoning in Palm Beach County on such an accusation. But Pauline Zile, who even prosecutors agree did not strike the blow that killed 7-year-old Christina Holt, may get the death penalty. Jessica Schwarz, who was found to have administered the beating that killed her 10-year-old stepson A.J., will be sentenced only on a second-degree murder conviction.

That contradiction has less to do with the law than with one simple fact: Jessica Schwarz was A.J.'s stepmother; Pauline Zile was Christina's natural mother. Prosecutors played to the public hatred of Pauline Zile with their push for a first-degree murder indictment and their conduct of the case. When Assistant State Attorney Mary Ann Duggan began the prosecution's closing argument Monday, she got right to the point: ``This case is about Christina Holt. She did not have a judge or jury to protect her. She had a mother to protect her.''

Pauline Zile was charged with felony murder, meaning that she wasn't accused of the killing herself, but of participating in the events that led up to Christina's death and caused it. So Ms. Duggan took a long time explaining what prosecutors had to prove and what they didn't have to prove. She talked about legal responsibilities for natural parents. But soon enough, Ms. Duggan was working the heartstrings again. Christina was an ``inconvenience'' to Zile. Christina had ``absolutely no hope.' ' Over and over, she referred to Zile as the ``natural mother.''

Ms. Duggan spoke for about an hour. After lunch came Assistant State Attorney Scott Cupp, who runs the Crimes Against Children Unit. As is his habit, Mr. Cupp pulled the podium close to the jury and spoke in a voice so low he could barely be heard in the third row of spectators. ``This is a case about a mother,'' he began.

He told how John Zile once dumped Christina in a dangerous West Palm Beach neighborhood, saying she could start from there if she wanted to run away. How Pauline Zile pawned Christina's pink bicycle just days before she died. He held up the tiny jeans Christina wore when she died, the jeans she wore when John Zile threw her body in a hole behind a Kmart.

Defense had little to work with

Zile's attorneys, Ellis and Guy Rubin, put on a good case. They showed where prosecutors lacked direct evidence, and there were several instances. For example, the defense lawyers pointed out that there were no eyewitnesses except John Zile. (A husband can't testify against a wife.)

But it became tragically clear that Christina Holt, whom Pauline Zile gave up shortly after her birth, was unwanted when she was sent back from Maryland to live with the Ziles last June. Pauline Zile's attorneys were left to concede that John Zile was ``a little aggressive.'' To say that John Zile did slam Christina on a bed and hit her with his belt, but he didn't do as much damage as if he had slammed her on the floor or the wall. To argue that the bruises John gave Christina were ``light bruises,'' and perhaps Pauline had overlooked them.

Mr. Cupp, however, could leave the jury with this hypothetical plea from Christina: ``Mommy, Mommy. I don't want to die.'' In the end, you could think only about the horror of the Zile household - and about the two boys in the photograph.

Randy Schultz is editor of the editorial page of The Palm Beach Post.

CHAMPION OF THE CHILDREN

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

April 16, 1995

Scott Cupp turned to the judge, eyes darkening like a thunderhead, and

delivered a final blow in Jessica Schwarz's murder trial: ``She despised

the boy.''

Assistant State Attorney Cupp

had not prepared his closing statement. He relied on his heart. His

zealous heart.

At the end, after the judge pronounced Schwarz guilty of killing her

10-year-old stepson, Cupp slumped forward, exhausted, relieved and deeply

sad.

For two years he had worked on the case, believing A.J. Schwarz was murdered when few others did. Now everyone knew and Cupp was inconsolable. Even with Schwarz facing life behind bars, there was no justice for A.J.

Hours later Cupp stood in another courtroom, facing another mother on trial for murdering her child.

Again, the verdict came back guilty. Prosecutor Mary Ann Duggan and Cupp succeeded in convincing jurors that Pauline Zile stood by and let her daughter be beaten to death. To many, the felony murder conviction was a surprise.

On a single day, Cupp and homicide prosecutors had won guilty verdicts in two of the most publicized cases in Palm Beach County's recent criminal history.

As the chief prosecutor of crimes against children, Cupp is at the front of the child abuse crusade, leading the charge. In the months ahead, he and homicide prosecutors will try Zile's husband, John, and three other mothers on murder charges.

Cupp's critics see him as a fanatic, turning his unreasonable wrath on the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services, drawing on the vulnerability of his victims to carry his cases and make a name.

But to his admirers, he is a champion for children - an Atticus Finch in the frenzied world of child abuse, providing a solid moral foothold and tenacity. Like Harper Lee's southern civil rights lawyer in To Kill a Mockingbird, Cupp does his lawyering methodically, propelling cases forward that might otherwise collapse in a fury of emotion.

Cupp sees himself as just a prosecutor who uses a lot of common sense and does what he thinks is right.

He knows that most of what he does would be too horrible for others to face: looking at the autopsy photos of children cut open, questioning a mother about drowning her child, comparing bruises and cigarette burns on a child's arm.

But he keeps going because he can't think of anything more important that he could be doing.

``Scott has the feeling. It's hard to explain,'' says his boss, State Attorney Barry Krischer.

``He's obsessed with incompetency. And he perceives there are people whose . . . job it is to protect children, and when he discerns complacency or worse, then he responds. When I get complaints from HRS, the fact is I agree with everything he's done.''

Where many prosecutors burn out trying the wrenching cases of children tortured, raped or murdered, Cupp remains grounded but passionate.

``The problem I've had historically is keeping prosecutors in that position who still maintain the fire in the gut . . . without just becoming real emotional basket cases,'' said Jerry Blair, state attorney for the Third Circuit and Cupp's former boss.

``It's a job that unfortunately attracts zealots and, you know, he has no less commitment than some of those who are more zealous, but he's able to balance that commitment.

``Scott never wavered. Scott is doing what he wants to do.''

`I'm not a perfect father'

Over the fireplace in Cupp's living room, a Christmas wreath still hangs. There are toys scattered in the den, where his two daughters, ages 6 and 4, play a game of restaurant, fighting over who will be maitre d'.

His wife, Susan, apologizes about the clutter, explaining that the past two months have been hectic.

``When he's in trial, you can tell. He's home, but he's in trial. He's always thinking about it,'' she said. ``I remember at one point, Scott couldn't sleep and would be up at 4 a.m. walking the floor and Scotty, (their 9-month-old son) would be up. I thought, `Am I ever going to get any sleep.' ''

In the Cupp household, Susan, 42, is the glue keeping the pieces in place. Her husband's job takes its toll. There are times he is rarely home.

The kids ``can feel it, they can perceive when there's tension. Most children can,'' Susan says. ``Katie (their 6-year-old) is really very interested in the news lately. But we do try to filter and simplify things so she can understand what her daddy does without it being too traumatic.''

When Cupp started working on the Zile case, Katie became upset that he might be breaking up a family.

``She was mad at me because, she said, `If the mommy goes to jail, and the daddy goes to jail, then there's no family.' That's very upsetting and I tried to explain that the mommy and daddy are not good to the little girl and the little girl is not safe.''

Then Cupp called a child psychiatrist to be sure he had said the right thing.

Like most parents, Cupp worries endlessly about his children.

``Believe me, I don't go around second guessing how people raise their kids,'' he says. ``I'm not some expert on raising kids. We struggle with it. We don't have perfect kids. I'm not a perfect father.''

Career led to children

How Cupp came to be an advocate for children is, well, almost boring. There is no dark history of abuse in his family, no single, enlightening case, no middle-of-the-night, cold-sweat awakening. It was simply where his career took him.

Cupp, 38, grew up as the baby in a middle-class family of three in Pittsburgh.

His father was a planning engineer for U.S. Steel. His mother raised the kids. Cupp thinks he came along as an afterthought: His sister is nine years older, his brother seven years. His childhood was bucolic: summer mornings letting the back door slam on his way out. Playing in the woods. Back in time for supper.

After high school, Cupp went to Penn State and promptly flunked out.

``I guess I wasn't ready for prime time,'' he shrugs.

For the next five years, he did odd jobs - driving a cab, working in a steel mill, selling cars and peddling insurance. Then, at 24, he decided to go back to school and enrolled at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. To his father's disappointment, he rejected sciences and majored in English literature. He had already decided to become a lawyer because two close friends were practicing and said they could find him work.

Being a pragmatic steel belter, Cupp was thinking about a job, not a passion.

During his third year at Western New England School of Law in Springfield, Mass., he worked in the criminal law clinic and tried two cases. He had already interned one summer in his friend's small general practice and realized family law was not for him. So, just before graduation, he lined up interviews at three state attorney offices in Florida because it was easier to get a job as a prosecutor here than in Pennsylvania.

At his first interview in Fort Myers he was offered a job. Cupp canceled interviews in Broward and Dade counties and spent the rest of the time on the beach.

For nearly two years, he handled juvenile, misdemeanor and drunken driving cases before moving on to felonies. Then, at a seminar in Fort Lauderdale, Cupp met his wife, who handled public relations for a cable company. Cupp groans at having to repeat how they met.

``It's so terrible,'' he says.

Sitting at Shooter's, one of South Florida's hottest meat-market bars in the mid-1980s, Cupp introduced himself to his future wife. They made plans to have dinner one night, then started dating bi-coastally.

``One of the first things that struck me was his sincerity,'' Susan says. ``He's very, very honest.''

Years later, Krischer also would remember Cupp's honesty when he considered him for the head of his crimes against children unit.

Four months after Cupp met Susan, he proposed. In 1987, he took a job in Palm Beach County so the couple could live on the same coast. In his first year, he helped another assistant state attorney prepare a molestation case against David Allen Lindsey Sr. - a 45-year-old cabinetmaker once seen as a hero for opening his house to troubled boys.

Lindsey was convicted in 1988 - it was Cupp's first big child abuse case and would shape his career.

But the state attorney at the time, David Bludworth, said he wanted Cupp back prosecuting felony cases. Cupp took a pay cut and moved to the rural Third Circuit to prosecute crimes against children in the small towns of northern Florida.

``That was a very big challenge,'' Susan Cupp says. ``It all happened so quickly. We closed on a house (in Coconut Creek in Broward County), Kate was born and eight months later we moved to this rural area. He was always so positive and said, `It'll pay off.' ''

Susan stayed behind trying to sell the house, unable to leave for another nine months.

In and around Suwannee County, Cupp learned what worked and what didn't. Blair remembers that even then, Cupp grew frustrated with the system created to protect children.

``He did not have a great deal of tolerance for HRS in activities regarding children,'' Blair said. ``Most of the individual workers had a good rapport with Scott, but I cannot say that the hierarchy was all that upset when he left.''

Krischer sought advocate

Even before he was elected in 1992, Krischer knew he wanted Cupp to prosecute crimes against children for him. Krischer, once Bludworth's chief assistant, had spent the last nine years in private practice and acting as an attorney for the Child Protection Team. He knew the state attorney should be doing more for children.

Cupp caught his attention during a DUI case about 1988. Krischer's client claimed Palm Beach County deputies beat him. Cupp discovered part of a video tape of the arrest had been erased and told Krischer.

Just after Krischer was sworn in 1993, Cupp took over the unit. Five months later, A.J. Schwarz was found dead, floating naked in his backyard pool.

``At that point, we didn't even know what we had,'' Cupp said. ``There was a pretty strong suspicion something was wrong in that home. That didn't take a rocket scientist.''

Detectives collected evidence and statements with Cupp overseeing legal aspects. Several months later the grand jury charged Jessica Schwarz with witness tampering, child abuse and murder and HRS caseworker Barbara Black with extortion for allegedly threatening a mother who called the abuse hot line about Schwarz. The grand jury also slammed HRS in a scathing report.

Then in late 1994, seven other parents - John and Pauline Zile, Timothy and Paulette Cone, Clover Boykin, Joanne Mejia and Jacqueline Caruncho - were charged in quick succession with murdering children. A grand jury indicted them and again issued a critical report.

Cupp was now seen as launching an attack on HRS.

``The more I got involved in child abuse, the more I realized the importance of emotional abuse,'' he said. ``The physical abuse stands out and people notice it, but it's the emotional toll. It basically destroys their spirit and that's what incenses me.''

Even HRS district administrator Suzanne Turner sees his point.

``I think - and I'm sure it's based on Scott's work in the process - (the jury and judge) have sent a clear message to the parents that they are responsible for the children and this society is not going to tolerate abuse and neglect,'' she said.

Then she said, ``I'm sure there are people all over town who agree or disagree with the State Attorney's Office just as they agree or disagree with HRS. I don't see us having an adversarial role.''

`We make a difference'

Back at his house, Cupp is taking a few days off. His girls are glad to have him home. His son is teething. Cupp's glad to be home.

``When I first started this, we'd just had our first child and I didn't think about it,'' he said. ``Sometimes it helps having kids. They help me. It's nice to come home to kids you know are happy.''

For all his victories at trial, Cupp says he has only once stepped up to a parent outside court.

He and his family were eating dinner when he noticed another father growing more and more angry with his toddler. Suddenly the man grabbed the boy by the arm and marched him outside. A few minutes later the man returned without his son. Cupp walked outside and found the boy locked in a car.

``He was a big guy and I went up and said, `Go get him,' and he did,'' Cupp says, remembering how scared he was.

Every time a child dies mysteriously or gets hit or raped or tortured, his heart sinks. Susan Cupp knows that feeling:

``Scott was at the police station and called about 11:30 p.m. and said he got a confession (from John Zile) and they were searching for the baby. I put a face on that little girl and I felt real pain. You hang on to that glimmer of hope that it's not that bad.''

Cupp is afraid of sounding sappy in explaining why he stays in crimes against children.

``To say it's important is overstating the obvious. I don't know if I could go back and try other cases. If I had to try drug cases, I'd go screaming into the night. I guess it's that sometimes, not all the time, we make a difference.''