Home --> AJ's Story --> AJ's Story: Newspaper Articles --> 1997 - 2005 Articles

A.J.'s Story

- Newspaper Articles

The following links take you to various articles in AJ's story as it

appeared in the South Florida media.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE INFORMATION ON THIS SITE BEFORE ASKING.

Thank you!

|

|

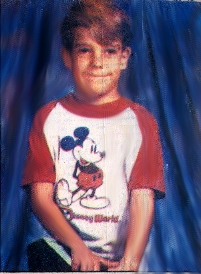

In Loving Memory Of Andrew James "A.J." Schwarz April 24,1983 - May 2,1993 "Beautiful Child who has found love from the angels...RIP..." |

|

This

page contains articles from the Palm Beach Post and The Sun-Sentinel

from the years 1997 - 2005. |

|

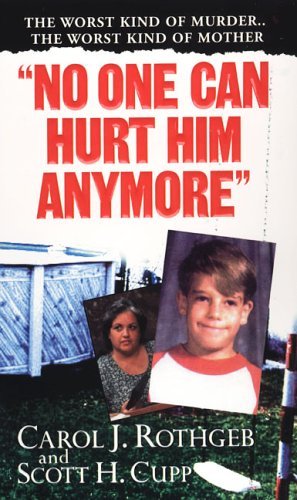

If you are interested in reading the FULL DETAILS of this case aside from what is posted here, please purchase "No One Can Hurt Him Anymore" by Carol J.Rothgeb and Scott H. Cupp. Mr. Cupp thinks it's the book that nobody will read...please show your support and show him that you care about AJ, too by ordering his book by clicking on the cover image below.

1997

They All Died Young, But Spare The Others (1/23/97)

State Worker Won't Be Tried in Threat Case (4/10/97)

Stepmom's Conviction Upheld in Killing: Appeals Court Rejects Lack-of-Evidence Claim in Murder of AJ Schwarz (6/5/97)

1998

New

Project To Help Protect Kids in State Custody From Abuse (3/11/98)

Turf War Grows Over Child-Death Review Panel (3/12/98)

Mom Struggles To Sustain Kids' Abuse Campaign (4/20/98)

Appeals Court Upholds Murder Conviction (7/30/98)

2004

Prosecutor Pens Story of the Boy He Can't Forget (2/21/04)

2005

Prosecutor's

Book Reveals Insight on Child Murder Case (5/22/05)

Book Details Boy's Short, Painful Life (7/5/05)

Prosecutor Details Murder of Boy, 10 (7/25/05)

THEY ALL DIED YOUNG, BUT SPARE

THE OTHERS

The Palm Beach Post

January 23, 1997

Two years ago, a grand jury investigating the deaths of four Palm Beach

County children determined that the state had failed in its mission

to protect kids from abuse.

The state had failed 7-year-old Christina Holt. And 10-year-old A.J.

Schwarz. And 2-year-old Pauline Cone. And 6-year-old Tremaine Kerr.

And 3-year-old Maya Self. And infants Dayton Boykin, Kayla Basante,

Tiffany Greenfield and Charles Mejia.

All their cases now have been through the courts. Some of those responsible

are in prison. In most cases, however, an adult knew the child was in

trouble but didn't call for help - or the call went unheeded. Christina

Holt was murdered during a beating by her stepfather, a beating neighbors

heard but ignored. A.J. Schwarz's naked and bruised body was found floating

in the family pool west of Lantana, and his stepmother was convicted

of his murder. Social service workers had been visiting the family for

months but found no reason to take A.J. from the home.

In addition to the grand jury, A.J.'s death gave prosecutors and police

impetus to examine how children are protected. A task force found problems

statewide. Most police and social workers focus on treating child abuse,

rather than trying to prevent it, the panel wrote to the Legislature

this month.

Recommendations include making it easier for aunts, uncles and grandparents

to take children instead of sending them to a stranger for foster care.

The task force also proposes increased subsidies for day care for kids

who come from troubled families - those without homes or those who live

with violent or drug-addicted parents. Social workers should be better

trained to determine when violence, drug or alcohol abuse are problems

at home. They should be paid more and should be required to pro ve their

competence.

And it does little good, the panel wrote, to pay for more police officers

if there aren't enough social workers to help a family stabilize after

a father has beaten his wife in front of the children.

The panel also concluded that state agencies need to communicate. The

Department of Children and Families, which oversees foster children,

and the Department of Juvenile Justice, which deals with young criminals,

work with many of the same children. But "their coordination is,

at best, dismal."

Some recommendations are being carried out. In Palm Beach County, a

"rapid response team" - a prosecutor, medical examiner, police

officer, member of the sheriff's office juvenile division and social

worker - goes to the scene when a child is found dead. Investigation

begins immediately, not days later, as was typical a few years ago.

More cases are being taken to trial.

Rep. Lois Frankel, D-West Palm Beach, the Legislature's expert on child

abuse, wants more money and accountability for child protective services.

"We need early visits at home," she said, "after the

child's born."

With much work and money, Florida has brought down its infant mortality

rate. The state must pay no less attention to the child mortality rate.

Back To Top

STATE WORKER WON'T

BE TRIED IN THREAT CASE

The Palm Beach Post

April 10, 1997

Author: VAL ELLICOTT

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Barbara Black, a state child-care worker accused of threatening a woman

for reporting a notorious child abuse case, will not face criminal charges

if she performs community service, a prosecutor said Wednesday.

"We felt at this point there would be no purpose served with a

trial," prosecutor Scott Cupp said.

Black, 36, of West Palm Beach was charged with extortion after she was

accused of vowing to take away Eileen Callahan's children if Callahan

continued calling the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services

- now the Department of Children and Families - to say that a neighbor's

child was being abused.

The child, Andrew "A.J." Schwarz, was later found dead. His

stepmother, Jessica Schwarz, 42, of Lake Worth, is serving a 40-year

sentence for second-degree murder in the case and a separate 30-year

sentence for abusing A.J.

Under the pretrial intervention agreement, finalized within the past

week, Black will perform community service each month for six months,

her attorney, Doug Duncan said. If she completes the community service,

the charge will be dropped.

Cupp said Callahan and sheriff's deputies supported that resolution.

"The problems that were present with HRS at the time all this came

down have for the most part been alleviated," he said. "The

agency is much different now."

Back To Top

STEPMOM'S CONVICTION UPHELD IN KILLING

APPEALS COURT REJECTS LACK-OF-EVIDENCE CLAIM IN MURDER OF A.J. SCHWARZ

Sun-Sentinel

June 5, 1997

Author: SCOTT GOLD Staff Writer

An appellate court on Wednesday upheld the conviction of Jessica Schwarz,

nearly two years after she was sentenced to 40 years in prison for the

murder of her 10-year-old stepson, who was found nude and beaten in

the family swimming pool.

Schwarz has always maintained that she was a victim herself - a victim

of a conspiracy, of misguided charges, of bad legal advice

But the 4th District Court of Appeal's ruling is a vivid reminder of

a case backed by 20 witnesses who outlined how Schwarz humiliated Andrew

"A.J." Schwarz, making him eat his meals next to the cat litter

box or run naked through their neighborhood west of Lantana.

The appeals court's ruling recounted, for example, testimony that Schwarz

hated A.J., that she thought he was "no good," that she wanted

to kill him. In May 1993, a neighbor testified, the night before A.J.

was found dead in the pool, the boy was heard saying, "I won't

do it again." It was followed by a "muffled crying-type noise."

The District Court of Appeal's discussion focused on charges, made by

Schwarz's attorneys, that there was not enough evidence to convict her.

During the trial, Schwarz's attorneys attempted to show that A.J.'s

death was a suicide, an accident or the work of another person.

The debate resurrects a sensitive time for Palm Beach County. Before

the trial, then-Palm Beach County medical examiner Dr. James Benz ruled

that A.J. had accidentally drowned. Benz would eventually step down

in June 1996, after months of debate over his competency.

Prosecutors hired a second expert, Dr. Joseph Burton, the chief medical

examiner in DeKalb County, Ga., to refute Benz' findings.

During the trial, Burton testified to a "medical certainty that

this is not a suicide." And he testified that A.J. had matching

lacerations behind each ear that were likely left behind by someone

forcing him into the pool and holding him underwater.

That and other testimony led the Court of Appeal to find that there

was enough evidence to convict Schwarz.

"The State is not . . . required to rebut every possible scenario

which could be inferred from the evidence," the Court of Appeal

ruled. "Rather it must introduce competent evidence which is inconsistent

with the defendant's theories. We find that there was . . . ample evidence

that she did commit the crime."

In all, the former truck driver is serving a 70-year sentence, including

an additional 30-year sentence, which she also appealed unsuccessfully,

for abusing A.J. before his death.

The ruling could be appealed to the state Supreme Court, but prosecutors

say there is nothing in it that would compel the Supreme Court to hear

it.

"We were confident in the case," said Ken Selvig, chief assistant

in the Palm Beach County State Attorney's Office. "We expected

it to be affirmed.

Back To Top

NEW PROJECT TO HELP PROTECT KIDS IN STATE CUSTODY FROM ABUSE

The Palm Beach Post

March 11, 1998

Author: William Cooper Jr.

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

If A.J. Schwarz were in state custody today, he might find a much different

child protection system than the one that led to his death in 1993.

At least, that's what state and local officials said Tuesday as they

unveiled a $2.9 million child abuse project designed to prevent the

kinds of mistakes that cost children their lives.

``This project is a seamless safety net for our children,'' said Eleanor

Weinstock, chairwoman of the Children's Services Council.

Two years ago, following a rash of child abuse deaths, the Department

of Children and Families, the children's council and a host of other

groups began meeting to ``re-engineer'' Palm Beach County's child protection

system.

The result was the Child Abuse Privatization Pilot Project, which shifts

some of the duties of DCF to nonprofits. The project, which expects

to serve 200 kids in its first year, gives agencies greater flexibility

to help abused children and their families, organizers said.

Unlike in 1993, when Schwarz was found floating bruised and naked in

his family's pool, the project enables children in abuse and neglect

cases to have an independent social worker to monitor the families'

needs. Boys Town of South Florida, a nonprofit organization that specializes

in case management, will use ``consultants'' to work with families to

help them ``navigate'' the system, said Keith Diederich, regional director

of Boys Town.

The project also enables DCF investigators to focus solely on work related

to investigations, instead of trying to find temporary homes for children

removed from their parents. The Children's Place/Connor's Nursery now

assumes the task of finding shelter homes for the county's abused children

taken into state care.

Ed Horton, local DCF administrator, welcomes the change. He believes

the new approach will raise the level of accountability among his staff

and the agencies handling child abuse cases.

With help from the Quantum Foundation, a $1 million ``bank'' has been

established to pay for services such as counseling and parenting classes

that Medicaid and private insurance don't cover. Using the managed-care

model, organizers have created a network that gives these families a

choice of services.

How it works

Here's how the child abuse privatization pilot project will work:

1. Abuse allegation is made to the 1-800-96ABUSE hot line.

2. The Department of Children and Families investigates.

3. If the child is removed from the home, the Children's Place/Connor's

Nursery finds a shelter home, where the youngster is housed temporarily.

4. A Boys Town consultant is assigned to the case to help the family

navigate the system.

5. A team of professionals and the family meet to determine the family's

needs within 30 days.

6. The family is referred to the managed-care type of network of service

providers.

SOURCE: The Child Abuse Privatization Pilot Project

Back To Top

TURF WAR GROWS OVER CHILD-DEATH

REVIEW PANEL

The Palm Beach Post

March 12, 1998

Author: William Cooper Jr.

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

A turf war is brewing between the state and a nonprofit group that

is creating Palm Beach County's first child-death review committee.

Home Safe, an agency that provides space where abused children are

interviewed, organized a 17-person committee that will meet March

25 to analyze 20 local child deaths that occurred in January. The

deaths include everything from premature births to drownings.

The committee consists of the medical examiner, the health department,

police and a host of other law enforcement and medical officials.

Home Safe's assumption of the lead in the reviews doesn't sit well

with Ed Horton, head of the local office for the Department of Children

and Families.

``Who empowered the people at Home Safe to be in charge?'' he asked.

Horton, whose agency investigates child abuse and neglect, agreed

two weeks ago to work with the Children's Services Council to start

a similar committee. The two joined forces after an internal DCF report

was made public that showed 15 local children died of abuse or neglect

during the 1995-96 budget year.

That figure was the highest in Florida at the time, and three times

the county's annual average.

Horton questions whether Home Safe has the authority to organize a

child-death review committee. He also has reservations about Suzanne

Turner, Home Safe's executive director, leading the effort.

``They don't have the appropriate credibility,'' said Horton, who

will take his concerns to the committee. ``If you look at the person

who is the chief executive (at Home Safe), she was connected with

the past child-abuse deaths.''

In fact, Turner held Horton's job from July 1993 until November 1996,

when she was hired by Home Safe. During her tenure, the county experienced

its highest number of child-abuse deaths, including the case of 10-year-old

A.J. Schwarz, who died in 1993 at the hands of his stepmother.

DCF's handling of the Schwarz case led a county grand jury to conclude

that abused children were ``at significant risk for further abuse''

after they entered the state's care. Turner could not be reached for

comment.

In Home Safe's defense, State Attorney Barry Krischer, who is a member

of the agency's board, said DCF and any other agencies had plenty

of time to organize a child-death review committee.

``The fact is, everybody was talking about it, but Home Safe took

it and ran with it,'' he said.

Krischer, meanwhile, took Home Safe's cause to Tallahassee.

He said Attorney General Bob Butterworth showed the most interest

and agreed to help find either state or federal money to help pay

for the project.

Back To Top

MOM STRUGGLES TO SUSTAIN KIDS' ABUSE CAMPAIGN

The Palm Beach Post

April 20, 1998

Author: William Cooper Jr.

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Kathy Forrester, a stay-at-home mom upset about the number of local

child abuse deaths in 1994, decided to do more than talk about the

problem with friends over coffee.

She volunteered to help launch Our Community, Our Children, a nonprofit

agency whose mission was to begin a massive child abuse prevention

campaign.

Initially, the group flooded the community with blue and white bumper

stickers, refrigerator magnets, T-shirts and tote bags promoting the

agency's theme, ``No Excuse For Child Abuse.''

Public service announcements filled radio and television - compliments

of the media. Local donations, totaling about $30,000, paid for printing

and distribution of information fliers.

Now, four years later, much of that momentum has waned, and Forrester

is struggling to keep the agency's doors open.

The organization was born out of the deaths of Christina Holt in 1994

and A.J. Schwarz in 1993.

``This organization exists because those children died,'' said Forrester,

who now is serving as an unpaid executive director of the agency.

``I had to pay my dues, but while I'm doing that, people need to know

that children are still dying.''

The turning point for the nonprofit organization happened in the spring

of 1996, when Forrester submitted a $160,000 proposal to the Children's

Services Council, which uses tax money to pay for new children's programs.

Forrester wanted the money to pay for staff, develop a public awareness

campaign and to distribute information packets about parenting. CSC

rejected it, saying Forrester's goals seemed too ambitious for such

a young agency.

After that setback, several board members left or just stopped coming

to the meetings, said Steve Vooglesang, a local tax attorney and original

board member.

``I think everybody was a little disappointed,'' Vooglesang said.

The rejection touched a nerve with Forrester. From the beginning,

she quietly questioned whether she was the person to lead Our Community,

Our Children.

She was a homemaker, with no college degree and no expertise in children's

issues. Yet being a new mother drove her to get involved.

In a matter of months, she went from being a volunteer to leading

an agency that was charged to educate the community about child abuse.

Forrester now is distributing the ``Parenting Pouch,'' an informational

guide for new parents. It has resources, including telephone numbers

where parents can get advice or counseling about raising their children.

``I don't care how many doors get slammed in my face, I'm not going

to stop trying,'' Forrester said.

Currently, she's applied for grants from the Community Foundation

of Palm Beach and Martin counties and the Quantum Foundation so the

agency can continue to distribute information about parenting tips

and child safety to the community.

Over the years, the agency has survived on small grants from the Department

of Children and Families. Corporate sponsors and efforts to raise

money never have reached the group's initial expectations.

Tana Ebbole, CSC's executive director, said the intent wasn't for

her agency or any other governmental entity to be Our Community, Our

Children's sole source of financial support.

``That's why we titled the organization the way we did . . . ,'' she

said.

Ebbole believes people in the private sector often are uncomfortable

with talking about child abuse and do not get involved financially.

Their uneasiness leaves the bulk of the responsibility to government

agencies.

``We need to have an aggressive, ongoing community awareness campaign

on child abuse,'' Ebbole said. ``It's every citizen's responsibility

to send a message that we will not tolerate children being abused

or being killed.''

Recently, Forrester took steps to revive Our Community, Our Children.

She's gone from running it from her Palm Beach Gardens home to a West

Palm Beach office at 2247 Palm Beach Lakes Blvd.

She's recruited new board members and is negotiating with new corporate

sponsors.

Toby Chabon, owner of Chabon and Associates, a career development

and human resources consulting firm, now heads the board. Chabon brings

nearly 20 years of child advocacy to Our Community, Our Children,

including serving on the county's Foster Care Review Committee and

as past president of the Center for Children in Crisis, a nonprofit

agency that provides counseling for abused children.

``I like challenges,'' Chabon said. ``This is an issue we all must

be involved in on a regular basis, not when we're just reacting to

startling headlines.''

Back To Top

APPEALS COURT UPHOLDS MURDER CONVICTION

Sun-Sentinel

July 30, 1998

Author: Staff reports

An appeals court on Wednesday upheld the conviction of Jessica Schwarz,

43, who was sentenced three years ago to 40 years in prison for the

murder of her 10-year-old stepson, only to claim that she was the

victim of poor legal advice.

The 4th District Court of Appeal ruled that even if Schwarz's defense

team allowed improper evidence to creep into the prosecution's case

in 1995, it did not affect the outcome of the trial.

Schwarz's stepson, Andrew "A.J." Schwarz, was found nude

and beaten in the family swimming pool in 1993. Prosecutors presented

20 witnesses who outlined how Schwarz humiliated A.J., making him

eat meals next to the cat litter box or run naked through the neighborhood

west of Lantana.

The testimony in question revolved around a medical examiner's conclusions,

which were based in part on what he heard neighbors say, not his own

work. But the appellate judges ruled that even if that testimony had

been quashed, Schwarz still would have been convicted.

Schwarz, a former truck driver is serving an additional 30 years for

abusing A.J. before his death.

Back To Top

PROSECUTOR PENS STORY OF THE BOY HE CAN'T FORGET

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

February 21, 2004

Author: Emily J. Minor

Scott Cupp remembers the details. The date of death. The address where

the boy died. The neighbor's name and the sister's name and the doctor

in Atlanta who performed the second autopsy.

Sometimes, he remembers these things all too well.

For years, Cupp, 47, has prosecuted only the tough, emotional cases

involving the abuse and death of children. "I don't know why,"

he says. "Sometimes I wonder that myself." First, in North

Florida, then in Palm Beach County, now on the west coast in Fort

Myers.

When you're a prosecutor, you tend to see the awful side of life.

And the awful side of life tends to stick.

Maybe you remember A.J. Schwarz? I know I do. There were other children

who died in Palm Beach County in 1993 - children who might even be

better-remembered than the slight boy with the abusive stepmother.

Christina Holt, the little girl whose mother pretended she'd been

abducted from a Broward County flea market when, indeed, the girl

was really dead - dead from a beating the mother had stood and watched.

Pauline Cone, a foster child who died when a wood lid on her crib

slammed down and hanged her.

On and on and on the list went. Mother after mother went to prison

- including Jessica Schwarz, A.J.'s stepmother.

But it was always this case and that boy Cupp remembered most.

A.J. Schwarz was 10 years old when he died SunFest weekend. Investigators

came to his house in Lantana on a hot Sunday morning, and it didn't

take too long for everyone to figure out something was up.

The boy was found floating naked in the family's backyard swimming

pool, his Ninja pajamas in a rumpled little pile inside a bedroom

that was so dim and stinky and sparse that investigators would make

note of it in their paperwork. He was bruised in odd places. In death,

his body was frozen in a weird contortion.

'Am I doing the right thing?'

And as the questioning wore on, Cupp and his team would discover things

were so bad - and Schwarz was so blatant with her abuse - that the

neighbors could list example after example of abuse.

"I started to do something with this in, like, February of 2000,"

says Cupp, who left Palm Beach County in 1999 and is now chief of

the felony division for the state attorney's office in the 20th Circuit.

"And there are times I wonder, 'Why am I doing this? Am I doing

the right thing?' "

Then he remembers all those details.

"He was trapped," Cupp said. "He really was."

Now, Cupp and a coauthor are working on a book about it with Kensington

Publications Inc. and hoping for a publication date of March 2005.

There was something sad, of course, about every one of the children

who died that year. There always is. But for so many of us, the story

of A.J. stuck. His stepmother hated him so much she made him eat from

a bowl on the floor, next to the cat litter. He walked to school in

the rain, but she always drove her own children - often whizzing right

by A.J.

Perhaps worst of all, A.J. watched his sister, older and mouthier,

get removed from the home - rescued, if you will - by state authorities

while he was left behind, scared and silent. A state worker was later

indicted for threatening to take a neighbor's children if the woman,

who'd repeatedly reported the abuse, continued to meddle in A.J.'s

troubled life.

"The kids' names change," said Cupp, who Friday morning

clipped another story of another child's death from another Florida

newspaper.

"It used to be A.J. and this one and that. Now there are just

different names."

All this is in the book, the one he's afraid no one will read. "It's

too awful," he says.

All this is in the book that Scott Cupp knows he has to write.

emily_minor@pbpost.com

Back To Top

Prosecutor's book reveals insight on child murder case

By DENISE ZOLDAN

dczoldan@naplesnews.com

May 22, 2005

Former Palm Beach County prosecutor Scott Cupp stops talking for a moment. His voice cracks and he can barely keep from crying. It's been 12 years and dozens of prosecutions later, but the murder of A.J. Schwarz, a 10-year-old Palm Beach County boy, at the hands of his stepmother still rips Cupp apart. That's why he's written a book, "No One Can Hurt Him Anymore" — an insider's story about how politics and egos can thwart justice. And how a system that's supposed to protect children often fails them.

The book, published by Kensington Publishing Corp., went on sale in local book stores this month. "It bothered me what this kid went through. He was in the custody of (the state). He should have been saved. It was infuriating. It's still infuriating," Cupp said from his third-floor office in the Lee County Justice Center, where he has been a prosecutor with the Southwest Florida State Attorney's Office for 2½ years.

Last year, Cupp, known statewide among prosecutors and law enforcers as a fierce champion of children, was the lead prosecutor in the Nelson Faerber case. It was one of the most high-profile child abuse cases in Collier County history. Faerber, a former Collier County School Board member, was accused of sexually assaulting a boy for years. A lifelong Naples resident and criminal defense attorney, Faerber had ties to the legal community that created a sensitive climate. Cupp was an outsider. No ties. He was the right man. For months, Cupp pressed hard as officials gathered mounting evidence. State investigators had rounded up other alleged victims when Faerber, professing his innocence, ended it all by taking his own life. "It was a tragic situation all the way around," said Steve Russell, Cupp's boss and State Attorney for Southwest Florida's 20th Judicial Circuit. "But I thought Scott was on track." Almost three years ago, Russell persuaded Cupp to take the assistant state attorney position overseeing 28 prosecutors in the felony division of the Lee County office. Cupp already had left the Palm Beach County State Attorney's Office. He was gearing down and had moved to LaBelle, where he had started a private practice. But Cupp always had wanted to head a felony division. And Russell is glad Cupp didn't turn him down. "He certainly has helped me achieve my goals of prosecuting child abuse," Russell said.

In the case of A.J. Schwarz, Cupp was an assistant state attorney in Palm Beach County when the boy drowned in 4 feet of water in the above-ground pool in his own back yard. Cuts and bruises in various stages of healing covered his body. He was found naked with fresh abrasions on his face and arms.

But no one was going to answer for A.J.'s death. The medical examiner's office ruled the manner of death "undetermined," making it impossible to bring murder charges that would stick. "I don't know how you even present to a grand jury when the medical examiner's going to tell them he can't tell if it's a homicide," Cupp said. But Cupp couldn't take "undetermined" for an answer. As the head of the Crimes Against Children Unit in the Palm Beach State Attorney's Office, he would do whatever it took to get to the truth. Cupp took on the medical examiner's office, the Florida Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services (now called the Department of Children and Families), and a list of critics before leveling child abuse and murder charges against Jessica Schwarz, A.J.'s stepmother.

Then, in a dubious political climate, Cupp delivered an impossible case to jurors, exposed the medical examiner and the state's child protection system for what they were, and put Jessica Schwarz behind bars for 70 years. If it weren't for Cupp, A.J.'s case never would have been filed, let alone successfully prosecuted, said his former boss, Barry Krischer, state attorney for Palm Beach County. Voters had just elected Krischer to office in 1993 when A.J. was murdered. And Krischer had just brought Cupp down from the 3rd Judicial Circuit in Lake City, where he was making a statewide name for himself prosecuting crimes against children.

In 1992, Cupp successfully had prosecuted the Lake City parents of a disabled child who died because their End Times religion didn't believe in doctors. Before that, Cupp sent to prison David Lindsey, one of the first single men in Florida allowed to adopt children. Lindsey got 15 years for sexually abusing his adopted sons. Cupp doesn't even attempt to conceal his disdain for inept officials in authority who fail to protect children. "They were feeding (Lindsey) kids like they were cookies," he said of the adoption agency.

But years later it would be 10-year-old A.J. who would continue to rip at Cupp's heart. "I don't know what A.J.'s plight resounded with him, but clearly he felt driven to do something about what happened, to his credit," Krischer told the Daily News. It was A.J.'s suffering and humiliation from physical and emotional abuse, Cupp said. It was relentless. His short life was torture and it appeared his death mattered to no one. And his killer was going to get away with it.

"Why A.J.?," Cupp repeats the question. Cupp, 49, said he didn't suffer an abusive childhood while growing up in Pittsburgh where his mother was a housewife and his father was an engineer. But he focused on A.J. for several reasons. "In the beginning, the way it started out ... with the medical examiner not wanting to call it a homicide," he said. Cupp got Krischer to give him permission to have A.J.'s body flown to Georgia for a second opinion — unbeknownst to the Palm Beach County medical examiner. The brotherhood of medical examiners in Florida was tight at the time, so Cupp felt he had to go out of state to find a neutral opinion. Critics said he was committing career suicide to go up against such a popular medical examiner.

But, Cupp said, "We had to do something." "Everybody was pressing to find out as much as we could about (A.J.'s) background. We found out pretty quickly what this kid went through," he said. Jessica Schwarz had abused and humiliated A.J. daily, keeping him from school, forcing him to eat roaches, humiliating him publicly by forcing him to run down the street naked. She degraded him constantly and made him yell out loud while working in the yard that he was a stupid idiot.

Cupp was infuriated by the mental abuse A.J. suffered and he not only successfully prosecuted A.J.'s stepmother, but he got an HRS employee convicted for threatening neighbors because they repeatedly had called to report A.J.'s abuse. Although the book about A.J.'s life and murder, which was co-written with author Carol J. Rothgeb, is Cupp's first, it's not his first brush with publicity. The Sunday, April 16, 1995, edition of the Palm Beach Post featured a five-column front-page spread on Cupp. The headline calls him "Champion of the Children." He's pictured holding his two daughters, Kaitlin, now 16, and Elizabeth, now 14. His now 10-year-old son, Scottie, was just an infant at the time.

The article talks about a man "obsessed with fighting child abuse." But Cupp now says he never intended to become an advocate for children. He wasn't particularly interested in child abuse cases. He was merely following job opportunities. And he took the jobs that offered the most money. He has three children, he explained. And he makes no apologies for the reasons he wants to promote his book. He wants it to help pay for his children's college education.

But during his years of prosecuting,

Cupp's passion for protecting children turned into a calling. He successfully

prosecuted John and Pauline Zile for first-degree murder and multiple

counts of child abuse in 1997. The Ziles made national headlines when

they reported their daughter had been kidnapped from a flea market

in Palm Beach County. Cupp has contempt for parents who abuse children

— and for Pauline Zile in particular. She went on TV crying

and asking for help. "She said the child was with her and then

she disappeared. She was crying, 'Oh, my baby. Oh, my baby,'"

Cupp said. A controlling John Zile had beaten the child to death while

Pauline Zile did nothing. In such cases, child abuse prosecutions

"get in your blood," Cupp said. And with the attitude of

a man resigned to his destiny, he added: "Whether I like it or

not, this is what I am suppose to do." The record shows he is

good at it.

Back To

Top

BOOK DETAILS BOY'S SHORT, PAINFUL

LIFE

10-YEAR-OLD A.J. SCHWARZ DIED AT HANDS OF STEPMOM.

South Florida Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, FL)

July 5, 2005

Author: Peter Franceschina Staff Writer

No one who knew the little brown-haired boy can forget him.

Before A.J. Schwarz became another emblem of Florida's troubled child protection system, he was anxious to please and starved for affection, yet he knew to keep his mouth closed when it came to his home life.

It has been a dozen years since his cruel stepmother made it her life's mission to punish 10-year-old A.J. in rough ways and further break him psychologically.

Neighbors saw A.J. edging the lawn with scissors; his stepmother made him run down the street naked, in front of classmates; she would swear at him and call him harsh names; she was seen cuffing A.J. about the head, even punching him. Some days, A.J. stood in the yard all day long repeating humiliating phrases over and over: "My name is A.J. I lie on people to get them in trouble. I will never do it again."

The stepmother told a neighbor she was going to kill A.J. one of these days. Then neighbors woke up May 2, 1993, to police cars and emergency workers converging on Triphammer Road in Lantana. A.J.'s bruised, abraded and naked body was found in the backyard pool, eight days after his 10th birthday.

"After A.J. died, I dreamed about him, dreamed about him and dreamed about him. I had to go to counseling. I think about him every day," says Theresa Walton, 21, a neighbor who knew A.J. "Now, as a mother myself, I think about it. I don't think you can ever forget about it."

That is Scott Cupp's hope for a larger audience. He was the Palm Beach County prosecutor who struggled to find justice in A.J.'s death, at a time Palm Beach County was seeing several high-profile child deaths. Cupp and a co-author recently published a book detailing A.J.'s short, painful life.

"This was a story that deserved to be told," Cupp says. "It was something that always stuck with me, and it probably always will."

The book doesn't read like a thriller, because the investigation quickly points to abuse by someone in the home. The storyline is drawn from Cupp's inside view of the investigation and thousands of pages of documents, witness statements and court transcripts. Cupp and Carol J. Rothgeb, a Missouri author who largely handled the writing, tell a straightforward horror story, one that could be ripped from today's headlines.

The book's title, No One Can Hurt Him Anymore, comes from case notes made by A.J.'s court-appointed guardian, who thought he failed A.J. by not pushing to get him out of the house. One entry read, "God was unkind to Andrew... No one can hurt him anymore. In the end, we all failed him. I should have saved him; now I must live with my failure."

The book is a harsh indictment of the Florida Department of Children & Families, then known as the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services. The child-protection agency knew all about A.J., but its investigators couldn't save him. A grand jury highlighted the failures in A.J.'s case and made numerous recommendations to better protect children under state care.

Cupp, who now supervises felony prosecutions in Fort Myers, says the system has not gotten any better. "They just did a marketing change," he says. "They went from HRS to DCF. What has changed?"

Born and raised in Fort Lauderdale, A.J. and his stepsister were taken away from their natural mother, Ilene Soini-Schwarz, after the stepsister allegedly was abused by one of the mother's boyfriends. In November 1990, they were sent to live with A.J.'s father, David Schwarz, and his wife, Jessica, and her two daughters in Lantana. During the entire time, A.J. was supposed to be under the watchful eye of the social workers.

Despite eight reports that came into child-protection agency about Jessica Schwarz's abuse and bizarre punishments, Cupp writes that social workers thought A.J.'s meddling mother and nosy neighbors were making it up.

"We warned them over, over and over," says Soini-Schwarz, who was trying to regain custody of A.J., and has now become a social worker focusing on juveniles. "It's got to stop. Every time I turn around, another kid in state custody is dying."

Child-protection investigators found no signs of abuse. One social worker later was charged with threatening a neighbor with taking her children away if she made more abuse reports. By all accounts, Jessica Schwarz doted on her own two daughters. A.J.'s stepsister was removed from the home after complaining about abuse, but A.J. was left there.

"You think it's dangerous enough to remove her, why do you leave the other one there? They definitely failed him, definitely," says Walton, the former neighbor. "Now that I'm older and understand it better, it breaks my heart even more."

A.J. was seen in the neighborhood at 1:30 in the morning on May 2, walking the family dog. Another neighbor heard a boy's voice calling out in the middle of the night, "I won't do it again! I won't do it again!"

Jessica Schwartz, then a 39-year-old heavyset woman proud of being loud and telling everyone exactly what she thought, never shed a tear for A.J. -- until her ride to jail, after her second-degree murder conviction. It took prosecutors two trials to put Jessica Schwarz in prison for 70 years.

First, Cupp and co-prosecutor Joseph Marx, now a Palm Beach County judge, won convictions against Schwarz for six counts of child abuse. The murder conviction was based solely on circumstantial evidence. Schwarz adamantly, arrogantly, maintained her innocence.

"I wanted him to be happy and stay at the house and just grow up there with us," Schwarz told jurors in her first trial.

In the murder trial, Laura Perryman, a neighbor, testified Jessica Schwarz said she was going to kill A.J.

"I kept saying, `You don't mean that.' She says, `I do mean it,'" recalls Perryman, who still lives in the same house. "He was so quiet and polite. Whatever I saw of him was the sweetest kid."

While Perryman thinks often about A.J., and never without becoming upset, she says his memory has faded in the neighborhood. "The neighborhood has all turned over. No one around here knows about it anymore."

Jessica Schwarz's release date is set for July 2034, when she will be 79.

Andrew James Schwarz's memory is marked by a plaque at his school, Indian Pines Elementary. He is buried in Lauderdale Memorial Gardens, in Garden 26, Lot 3, Space 4.

Peter Franceschina can be reached

at pfranceschina@sun-sentinel.com or 561-832-2894.

Caption:

NEVER HAD a CHANCE: The book, No One Can Hurt Him Anymore, is a harsh

indictment of the DCF, then known as the Department of Health and

Rehabilitative Services. The child-protection agency knew all about

A.J., but its investigators couldn't save him. A grand jury highlighted

the failures in A.J.'s case and made numerous recommendations to better

protect children under state care. Staff photo/Scott Fisher

Back To

Top

Prosecutor details murder of

boy, 10

Lee attorney covers abuse case in book

By GRANT BOXLEITNER

GBOXLEITNER@NEWS-PRESS.COM

Published by news-press.com on July 25, 2005

The daily torture and eventual murder of 10-year-old Andrew "A.J." Schwartz at the hands of his stepmother affected prosecutor Scott Cupp in ways he can't always grasp.

Cupp, felony division chief in the Fort Myers state attorney's office, was once awakened by a heart-wrenching dream about the slain boy, who lived in Lantana in Palm Beach County.

"The case got so ingrained in my mind," he said.

It has been more than 10 years since Cupp faced off against the stepmother, Jessica Schwartz, in the courtroom as an assistant state attorney in Palm Beach County during the high-profile trial.

Cupp successfully prosecuted the former truck driver on criminal child abuse and second-degree murder charges after everything seemed stacked against the state's case from the first autopsy. Schwartz is serving a 70-year prison term.

Cupp chronicles the boy's torture, the stepmother's penchant for abuse and all the courtroom drama in the book "No One Can Hurt Him Anymore."

Cupp, who took the chief of felonies post in the Lee state attorney's office in 2003, is part of the prosecution team in Donald Moringiello's second-degree murder trial.

The 65-year-old Fort Myers Beach resident is accused of shooting wife Hattie "Fern" Bergeler-Moringiello four times, weighing her body down with concrete and dumping it in Estero Bay in 2002.

The trial continues today at the Lee County Justice Center.

From 1993 to 1999, Cupp served as division chief of crimes against children and sex crimes unit in Palm Beach County. He earned the nickname "Champion of the Children" among some of his peers after an article about him was published in the Palm Beach Post.

Co-written by author Carol J. Rothgeb, Cupp's book doesn't mask the pain and sadness that accompanies child abuse. Rothgeb knew the painful topic could shrink the audience base for the nonfiction title, which is available at most book stores and Web sites.

Rothgeb said she made sure she stopped writing several hours before bed because she didn't want A.J. to be the last thought on her mind.

"I had to detach as much as possible," said Rothgeb, who also penned the true-crime book "Hometown Killer." "I call what Jessica did creative abuse."

One example of such abuse highlighted in the book is forcing her stepson trim the grass around the driveway with scissors.

But A.J. probably was punched and kicked before he was thrown in the pool to die, Rothgeb said.

Cupp said he wanted to write a book about the case sooner but said the timing didn't present itself until he came to Fort Myers. He used hundreds of pages of transcripts from the trials, building the book's credibility with documented testimony.

Cupp decided to let a co-author help him write it, he said, because he knew he could not remain objective when it came to A.J.

"At least justice was done for A.J." Cupp said. "Jessica could have easily gotten away with murder."