Home --> AJ's Story --> AJ's Story: Newspaper Articles --> 1995 Page 4

A.J.'s Story

- Newspaper Articles

The following links take you to various articles in AJ's story as it

appeared in the South Florida media.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE INFORMATION ON THIS SITE BEFORE ASKING.

Thank you!

|

|

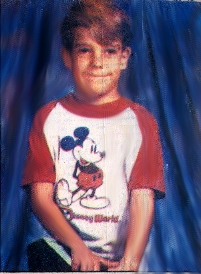

In Loving Memory Of Andrew James "A.J." Schwarz April 24,1983 - May 2,1993 "Beautiful Child who has found love from the angels...RIP..." |

|

This

page contains articles from the Palm Beach Post and The Sun-Sentinel

from the year 1995. |

|

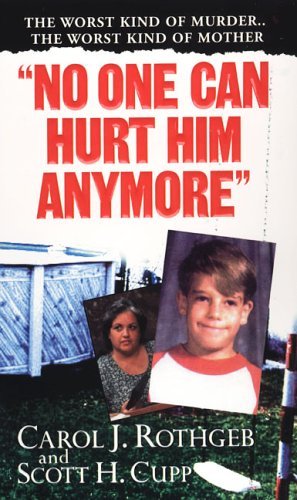

If you are interested in reading the FULL DETAILS of this case aside from what is posted here, please purchase "No One Can Hurt Him Anymore" by Carol J.Rothgeb and Scott H. Cupp. Mr. Cupp thinks it's the book that nobody will read...please show your support and show him that you care about AJ, too by ordering his book by clicking on the cover image below.

Champion of The Children (4/16/95)

1 in 8 Foster Homes Dirty, Crowded (4/17/95)

Not The Brady Bunch Anymore (4/18/95)

Estate of AJ Schwarz Sues HRS (5/2/95)

AJ's Mother Files Lawsuit Over His Death (5/2/95)

Around Town (5/6/95)

Prosecutors in Child Deaths Try To Stay Detatched (5/8/95)

When Children Die (6/2/95)

New Schwarz Trial Sought (6/10/95)

CHAMPION OF THE

CHILDREN

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

April 16, 1995

Scott Cupp turned to the judge, eyes darkening like a thunderhead, and

delivered a final blow in Jessica Schwarz's murder trial: ``She despised

the boy.''

Assistant State Attorney Cupp had not prepared his closing statement.

He relied on his heart. His zealous heart.

At the end, after the judge pronounced Schwarz guilty of killing her

10-year-old stepson, Cupp slumped forward, exhausted, relieved and deeply

sad.

For two years he had worked on the case, believing A.J. Schwarz was

murdered when few others did. Now everyone knew and Cupp was inconsolable.

Even with Schwarz facing life behind bars, there was no justice for

A.J.

Hours later Cupp stood in another courtroom, facing another mother on

trial for murdering her child.

Again, the verdict came back guilty. Prosecutor Mary Ann Duggan and

Cupp succeeded in convincing jurors that Pauline Zile stood by and let

her daughter be beaten to death. To many, the felony murder conviction

was a surprise.

On a single day, Cupp and homicide prosecutors had won guilty verdicts

in two of the most publicized cases in Palm Beach County's recent criminal

history.

As the chief prosecutor of crimes against children, Cupp is at the front

of the child abuse crusade, leading the charge. In the months ahead,

he and homicide prosecutors will try Zile's husband, John, and three

other mothers on murder charges.

Cupp's critics see him as a fanatic, turning his unreasonable wrath

on the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services, drawing

on the vulnerability of his victims to carry his cases and make a name.

But to his admirers, he is a champion for children - an Atticus Finch

in the frenzied world of child abuse, providing a solid moral foothold

and tenacity. Like Harper Lee's southern civil rights lawyer in To Kill

a Mockingbird, Cupp does his lawyering methodically, propelling cases

forward that might otherwise collapse in a fury of emotion.

Cupp sees himself as just a prosecutor who uses a lot of common sense

and does what he thinks is right.

He knows that most of what he does would be too horrible for others

to face: looking at the autopsy photos of children cut open, questioning

a mother about drowning her child, comparing bruises and cigarette burns

on a child's arm.

But he keeps going because he can't think of anything more important

that he could be doing.

``Scott has the feeling. It's hard to explain,'' says his boss, State

Attorney Barry Krischer.

``He's obsessed with incompetency. And he perceives there are people

whose . . . job it is to protect children, and when he discerns complacency

or worse, then he responds. When I get complaints from HRS, the fact

is I agree with everything he's done.''

Where many prosecutors burn out trying the wrenching cases of children

tortured, raped or murdered, Cupp remains grounded but passionate.

``The problem I've had historically is keeping prosecutors in that position

who still maintain the fire in the gut . . . without just becoming real

emotional basket cases,'' said Jerry Blair, state attorney for the Third

Circuit and Cupp's former boss.

``It's a job that unfortunately attracts zealots and, you know, he has

no less commitment than some of those who are more zealous, but he's

able to balance that commitment.

``Scott never wavered. Scott is doing what he wants to do.''

`I'm not a perfect father'

Over the fireplace in Cupp's living room, a Christmas wreath still hangs.

There are toys scattered in the den, where his two daughters, ages 6

and 4, play a game of restaurant, fighting over who will be maitre d'.

His wife, Susan, apologizes about the clutter, explaining that the past

two months have been hectic.

``When he's in trial, you can tell. He's home, but he's in trial. He's

always thinking about it,'' she said. ``I remember at one point, Scott

couldn't sleep and would be up at 4 a.m. walking the floor and Scotty,

(their 9-month-old son) would be up. I thought, `Am I ever going to

get any sleep.' ''

In the Cupp household, Susan, 42, is the glue keeping the pieces in

place. Her husband's job takes its toll. There are times he is rarely

home.

The kids ``can feel it, they can perceive when there's tension. Most

children can,'' Susan says. ``Katie (their 6-year-old) is really very

interested in the news lately. But we do try to filter and simplify

things so she can understand what her daddy does without it being too

traumatic.''

When Cupp started working on the Zile case, Katie became upset that

he might be breaking up a family.

``She was mad at me because, she said, `If the mommy goes to jail, and

the daddy goes to jail, then there's no family.' That's very upsetting

and I tried to explain that the mommy and daddy are not good to the

little girl and the little girl is not safe.''

Then Cupp called a child psychiatrist to be sure he had said the right

thing.

Like most parents, Cupp worries endlessly about his children.

``Believe me, I don't go around second guessing how people raise their

kids,'' he says. ``I'm not some expert on raising kids. We struggle

with it. We don't have perfect kids. I'm not a perfect father.''

Career led to children

How Cupp came to be an advocate for children is, well, almost boring.

There is no dark history of abuse in his family, no single, enlightening

case, no middle-of-the-night, cold-sweat awakening. It was simply where

his career took him.

Cupp, 38, grew up as the baby in a middle-class family of three in Pittsburgh.

His father was a planning engineer for U.S. Steel. His mother raised

the kids. Cupp thinks he came along as an afterthought: His sister is

nine years older, his brother seven years. His childhood was bucolic:

summer mornings letting the back door slam on his way out. Playing in

the woods. Back in time for supper.

After high school, Cupp went to Penn State and promptly flunked out.

``I guess I wasn't ready for prime time,'' he shrugs.

For the next five years, he did odd jobs - driving a cab, working in

a steel mill, selling cars and peddling insurance. Then, at 24, he decided

to go back to school and enrolled at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh.

To his father's disappointment, he rejected sciences and majored in

English literature. He had already decided to become a lawyer because

two close friends were practicing and said they could find him work.

Being a pragmatic steel belter, Cupp was thinking about a job, not a

passion.

During his third year at Western New England School of Law in Springfield,

Mass., he worked in the criminal law clinic and tried two cases. He

had already interned one summer in his friend's small general practice

and realized family law was not for him. So, just before graduation,

he lined up interviews at three state attorney offices in Florida because

it was easier to get a job as a prosecutor here than in Pennsylvania.

At his first interview in Fort Myers he was offered a job. Cupp canceled

interviews in Broward and Dade counties and spent the rest of the time

on the beach.

For nearly two years, he handled juvenile, misdemeanor and drunken driving

cases before moving on to felonies. Then, at a seminar in Fort Lauderdale,

Cupp met his wife, who handled public relations for a cable company.

Cupp groans at having to repeat how they met.

``It's so terrible,'' he says.

Sitting at Shooter's, one of South Florida's hottest meat-market bars

in the mid-1980s, Cupp introduced himself to his future wife. They made

plans to have dinner one night, then started dating bi-coastally.

``One of the first things that struck me was his sincerity,'' Susan

says. ``He's very, very honest.''

Years later, Krischer also would remember Cupp's honesty when he considered

him for the head of his crimes against children unit.

Four months after Cupp met Susan, he proposed. In 1987, he took a job

in Palm Beach County so the couple could live on the same coast. In

his first year, he helped another assistant state attorney prepare a

molestation case against David Allen Lindsey Sr. - a 45-year-old cabinetmaker

once seen as a hero for opening his house to troubled boys.

Lindsey was convicted in 1988 - it was Cupp's first big child abuse

case and would shape his career.

But the state attorney at the time, David Bludworth, said he wanted

Cupp back prosecuting felony cases. Cupp took a pay cut and moved to

the rural Third Circuit to prosecute crimes against children in the

small towns of northern Florida.

``That was a very big challenge,'' Susan Cupp says. ``It all happened

so quickly. We closed on a house (in Coconut Creek in Broward County),

Kate was born and eight months later we moved to this rural area. He

was always so positive and said, `It'll pay off.' ''

Susan stayed behind trying to sell the house, unable to leave for another

nine months.

In and around Suwannee County, Cupp learned what worked and what didn't.

Blair remembers that even then, Cupp grew frustrated with the system

created to protect children.

``He did not have a great deal of tolerance for HRS in activities regarding

children,'' Blair said. ``Most of the individual workers had a good

rapport with Scott, but I cannot say that the hierarchy was all that

upset when he left.''

Krischer sought advocate

Even before he was elected in 1992, Krischer knew he wanted Cupp to

prosecute crimes against children for him. Krischer, once Bludworth's

chief assistant, had spent the last nine years in private practice and

acting as an attorney for the Child Protection Team. He knew the state

attorney should be doing more for children.

Cupp caught his attention during a DUI case about 1988. Krischer's client

claimed Palm Beach County deputies beat him. Cupp discovered part of

a video tape of the arrest had been erased and told Krischer.

Just after Krischer was sworn in 1993, Cupp took over the unit. Five

months later, A.J. Schwarz was found dead, floating naked in his backyard

pool.

``At that point, we didn't even know what we had,'' Cupp said. ``There

was a pretty strong suspicion something was wrong in that home. That

didn't take a rocket scientist.''

Detectives collected evidence and statements with Cupp overseeing legal

aspects. Several months later the grand jury charged Jessica Schwarz

with witness tampering, child abuse and murder and HRS caseworker Barbara

Black with extortion for allegedly threatening a mother who called the

abuse hot line about Schwarz. The grand jury also slammed HRS in a scathing

report.

Then in late 1994, seven other parents - John and Pauline Zile, Timothy

and Paulette Cone, Clover Boykin, Joanne Mejia and Jacqueline Caruncho

- were charged in quick succession with murdering children. A grand

jury indicted them and again issued a critical report.

Cupp was now seen as launching an attack on HRS.

``The more I got involved in child abuse, the more I realized the importance

of emotional abuse,'' he said. ``The physical abuse stands out and people

notice it, but it's the emotional toll. It basically destroys their

spirit and that's what incenses me.''

Even HRS district administrator Suzanne Turner sees his point.

``I think - and I'm sure it's based on Scott's work in the process -

(the jury and judge) have sent a clear message to the parents that they

are responsible for the children and this society is not going to tolerate

abuse and neglect,'' she said.

Then she said, ``I'm sure there are people all over town who agree or

disagree with the State Attorney's Office just as they agree or disagree

with HRS. I don't see us having an adversarial role.''

`We make a difference'

Back at his house, Cupp is taking a few days off. His girls are glad

to have him home. His son is teething. Cupp's glad to be home.

``When I first started this, we'd just had our first child and I didn't

think about it,'' he said. ``Sometimes it helps having kids. They help

me. It's nice to come home to kids you know are happy.''

For all his victories at trial, Cupp says he has only once stepped up

to a parent outside court.

He and his family were eating dinner when he noticed another father

growing more and more angry with his toddler. Suddenly the man grabbed

the boy by the arm and marched him outside. A few minutes later the

man returned without his son. Cupp walked outside and found the boy

locked in a car.

``He was a big guy and I went up and said, `Go get him,' and he did,''

Cupp says, remembering how scared he was.

Every time a child dies mysteriously or gets hit or raped or tortured,

his heart sinks. Susan Cupp knows that feeling:

``Scott was at the police station and called about 11:30 p.m. and said

he got a confession (from John Zile) and they were searching for the

baby. I put a face on that little girl and I felt real pain. You hang

on to that glimmer of hope that it's not that bad.''

Cupp is afraid of sounding sappy in explaining why he stays in crimes

against children.

``To say it's important is overstating the obvious. I don't know if

I could go back and try other cases. If I had to try drug cases, I'd

go screaming into the night. I guess it's that sometimes, not all the

time, we make a difference.''

Back To Top

1 IN 8 FOSTER HOMES DIRTY, CROWDED

The Palm Beach Post

April 17, 1995

WILLIAM COOPER JR.

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

The first in-depth review of Palm Beach County's foster homes by anyone

outside the state bureaucracy found one in eight substandard and crowded,

state records show.

In a luck-of-the-draw system, some children went to clean, comfortable

homes with plenty of toys and strict but loving discipline. Others were

crowded into dirty places and left in the care of adults who spanked

them.

One home had no running water. One had no food in the refrigerator.

In another, children shared living space with a pig.

It wasn't just kids who suf-fered from a system with too-few options.

While some foster parents love what they do, a quarter told reviewers

they were overworked, angry and ready to quit.

The comprehensive review of the county's 189 foster homes was done last

summer by teachers and members of the Foster Parents Association of

Palm Beach County, who were paid $19,719 by the state Department of

Health and Rehabilitative Services.

``This was above and beyond what we normally we do,'' said James Hart,

the deputy District 9 administrator. ``We wanted adults with common

sense. As a result of the findings, HRS has closed some foster homes.

But the state agency could not say how many closings could be attributed

to the reviews. The agency is also using the information to improve

oversight and communication with foster parents.

The review showed that foster homes operated by private, non-profit

agencies, such as the Children's Home Society, were in better condition

than those operating through HRS. The private foster homes had fewer

children, more frequent visits from counselors and more money for therapeutic

services.

To create such an environment for HRS foster homes would cost ``thousands

of dollars,'' Hart said.

Because the visits were unannounced, many foster parents were caught

with messy homes. At least 22 foster homes were considered in conditions

below basic standards - including filthy rooms, roaches crawling on

walls and lack of screening to keep toddlers from slipping into swimming

pools or canals, HRS records show.

Some foster homes required emergency attention.

When reviewers arrived at the home of Richard and Marge Sweeney, they

found five foster children ``lined up like zombies on the couch.'' Reviewers

called the home ``an accident waiting to happen.''

The family had farm animals, including a pig, living in the home, according

to Hart.

``How could the health department pass this home?'' a reviewer questioned.

Marge Sweeney told reviewers the house was in disarray because her family

was in the process of moving. The family also wanted permission to allow

the foster children to sleep in tents until their new home was ready.

The residence at the time of the review had become too crowded, reviewers

noted.

Hart said he later visited the Sweeney home to make sure the problems

were corrected. The Sweeneys' request for the children to live in tents

was denied, he said.

The Sweeneys, still foster parents, have moved into their new home.

Hart said their home is ideal for foster children because it has plenty

of space.

``It's a very, very adequate home,'' Hart said. ``There's a pond with

ducks, and there's no sign of the animals in the house.''

Pig sighting was a shock

Marge Sweeney said last week she is not ashamed of having chickens,

ducks and pigs at her home. However, she could understand a visitor's

surprise at seeing a pig resting in the living room.

``I'm a kid lover and I'm an animal lover,'' she said.

Edison Ramirez, an HRS counselor who visits the home regularly, didn't

think the farm animals posed a threat to the children. Most of them

were kept inside a fence.

``The animals are therapeutic for the kids.'' Ramirez said.

Children are placed in foster care after a judge rules that the parents

can't adequately care for them. They usually are sent to foster homes

near their previous homes.

HRS officials said they try to match foster parents with the kind of

children they want. But often, social workers must scramble to place

the children in the first available home.

About 20 percent of the foster homes were over their licensed capacity,

HRS records show.

Some foster parents - who are paid between $306 and $421 a month per

child - acknowledged that constantly caring for unruly children has

worn their patience thin.

Take the home of Basilio and Antonia Ramos, where seven foster children

typically reside. Antonia Ramos told reviewers that ``sometimes seven

kids seems like too many.''

They have also had problems with one foster child who set their home

on fire a couple of years ago.

The child, who has been in 13 foster homes in six years, takes medication

for his behavior. HRS shows little interest, according to Antonia Ramos,

the boy's foster mother since 1991.

An HRS counselor once failed to take the boy to a doctor's appointment.

As a result, the doctor now refuses to see the youngster, Ramos said.

Ramos also complained she had no paperwork declaring her and her husband

as the child's foster parents. The lack of information kept them from

getting school records; it took three months to get the children enrolled.

``No one told them what a tremendous problem this child had,'' reviewers

wrote. ``The way Mrs. Ramos has been treated by HRS is a nightmare.''

The absence of background information on foster children was a complaint

among 21 percent of the foster parents, HRS records show. Some even

complained that when they got the information, it wasn't always accurate.

Many, like the Ramos family, had asked for the information, but HRS

officials ignored their requests.

Foster parents speak out

Foster mother Elizabeth Howard told reviewers she had to draw the line.

``She has learned to refuse taking children unless she has the information,''

reviewers wrote.

Although Howard's approach is drastic, it shows the kind of measures

foster parents must take to protect themselves and their families.

Shirley Fitzgerald, president of the local Foster Parents Association,

said the reviews allowed foster parents to speak candidly about problems

they encounter.

The drill helped give HRS decision-makers information that typically

doesn't make it to their level. The agency can now determine which homes

need fewer children, more training and additional services.

About 25 percent of the foster parents complained that HRS workers failed

to visit the foster children at least once a month as required by state

policy.

Among those who complained about a lack of visits were Timothy and Paulette

Cone, the Lake Worth couple who have been charged with first-degree

murder and child abuse in the death of their 2-year-old adopted daughter,

Pauline.

The toddler, a former foster child, died Nov. 10 when a plywood lid

rigged to her crib fell, strangling her. In July, during the inspection,

the reviewers noted that Paulette Cone ``needs support for herself and

children.''

The Cones, who told reviewers they had 60 foster children over five

years, have called Pauline's death an accident.

Although reviewers found the Cone home messy, they said the foster children

were ``well-groomed.'' They also concluded that the foster children

were ``very responsive to working with parents.''

Last April, HRS Secretary Jim Towey ordered all foster homes in Florida

inspected, after a 12-year-old foster child turned up at a Hillsborough

County hospital severely neglected.

Locally, however, such inspections should have been under way.

Four months before Towey's edict, Suzanne Turner, the local HRS district

administrator, announced inspections in response to charges accusing

Jessica Schwarz of killing her 10-year-old stepson while he was under

HRS supervision.

But inspections weren't made because HRS had problems organizing the

project.

Last May, local HRS officials decided to hire school teachers and representatives

from the Foster Parent Association to make the visits.

In teams of two, consisting of a foster parent and teacher, the group

went to the homes, armed with a five-page evaluation form. The ``inspectors''

reviewed everything from cleanliness to the foster parents' relationship

with the foster children.

About two-thirds of the county's foster homes seemed to be functioning

properly. Some foster parents did not cooperate with the reviewers,

refusing to even let them into their homes. For some, it took reviewers

at least three visits to inspect the home.

Some foster homes were given grades. Of 42 homes that were graded, 35

received a C or better. Seven were rated below average or failing.

Susan Rowe, a foster parent who helped inspect 78 of the homes, later

had her own home reviewed by HRS workers. Their report was unfavorable.

The reviewers noted ``all rooms in total disarray,'' and that she had

too many children in the home.

``Mom is a caring individual, however, she might be overwhelmed with

the number and needs of these special children and a household to run.''

Rowe said her review did not take place until last October, three months

after HRS formed the team. She said her home was crowded because HRS

called at 2 a.m. one day, asking her to take four siblings.

That pushed the number of children in her home to 12, including four

of her own children. In addition, Rowe had pneumonia.

``I was overwhelmed,'' said Rowe, adding that the four additional foster

children have since been moved. ``I didn't realize it until they were

taken out of the home.''

Some homes were surprisingly unsanitary, said Rowe. However, she said

she could understand why some families were caught with dirty homes.

`Held to higher standard'

``We're expected to be cleaner, neater and more respectful of the children's

needs,'' Rowe said. ``We're held to a higher standard than the biological

parents.''

Lynn Bogner, an HRS foster care analyst, said the state agency is putting

a new emphasis on training as a result of the reviews. HRS counselors

are attending the same training as the foster parents.

``The foster parents said they didn't know why the counselors were supposed

to come to the home,'' Bogner said.

For HRS counselors, the department is stressing the importance of monthly

visits, which should go beyond merely observing the foster children.

The social workers also should use the time to share information, ask

about the mental health of the foster parents and help meet the family's

needs.

Staff Writer Jane Victoria Smith contributed to this report.

RATING THE HOMES

Reviewers judged foster homes on whether they were clean, had activities

and toys for the children, whether discipline was administered properly

and whether the foster parents and kids had a good relationship. Here

are some that stood out:

MAX AND FRANCIS VESLOVSKY

CHILDREN: Two foster children, two biological children.

COMMENTS: The home was ``very nice, serene, calm, quiet, loving. No

help from counselors in getting services for the children.''

WILLIE AND VERONICA KING

CHILDREN: Four foster children, two biological.

COMMENTS: Home is `free of dangerous conditions.' Foster children have

`nice rooms.' Biological parents appreciate her taking care of their

children.

ROBERT AND DORREN HOWELL

CHILDREN: Four foster children

COMMENTS: Cares for children with some handicaps. Home has great toys

and play areas. Takes kids swimming, participates in gymnastics. Lots

of family activities. `Wonderful home - lots of love - great situation.'

STEPHEN AND BETH ECKMAN

CHILDREN: Two

COMMENTS: ` . . . very nice home, set up for children.' The foster children

participate in gymnastics, vacations and church activities.

REGINALD AND MILDREN GORDON

CHILDREN: Seven foster children, one biological child.

COMMENTS: Home was in good condition. Children have their own beds.

`Kids happy.' Difficulty getting information on foster children. The

family had to `call and beg for it.'

Source: state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services, foster

care visitor's project.

FOSTER HOME FINDINGS

Teachers and members of the Foster Parent Association visited 189 foster

homes last summer. Here are some of their findings:

SOME FOSTER PARENTS admitted spanking children in violation of state

policy.

OTHERS USED ODD FORMS OF DISCIPLINE such as making children do hand

stands or push ups, putting hot sauce on their finger tips.

MANY LOVE WHAT THEY DO, but a fourth say they are overworked, angry

and ready to quit.

ABOUT 20 PERCENT of the foster homes had more than five foster children,

the state's license capacity.

SOME 21 PERCENT complained that they had no background information on

the children placed in their homes.

A QUARTER OF THE FOSTER PARENTS complained that HRS counselors failed

to visit the children once a month as required by the state.

Back To Top

NOT THE BRADY BUNCH ANYMORE

The Palm Beach Post

April 18, 1995

FRAN HATHAWAY

Why are more parents killing their children?

In our revulsion at the recent spate of child deaths, have we decided

such behavior is inexplicable and stopped asking?

Yet there's a reason for everything. And last week, after two Palm Beach

County mothers were convicted of murder, a friend called to point out

that Jessica Schwarz, who killed 10-year-old A.J., was his stepmother.

And though Pauline Zile is culpable for watching while her 7-year-old

daughter Christina was beaten to death, it's stepfather John Zile who's

charged with the beating.

Stepparents. People trying to fill a caring role for children born in

another marriage to someone they love now. It's a much tougher job than

most admit. And many people aren't doing it very well.

That's not to offend stepparents who are working hard to blend their

families. And it's not my judgment. It comes from stepparents themselves

and from family therapists who have watched families split and try to

reform for a quarter-century.

Jeannette Lofas runs the Stepfamily Foundation in New York and has written

books on stepparenting. After telling her about the local murders, I

asked, gingerly, whether stepparenting might be a factor or simply a

coincidence. She replied without hesitation.

``Oh, it's a given there's more child abuse and sexual abuse in stepfamilies,''

she says. ``Your cases may be extreme. But lots of stepparents think

about killing their kids. And now we live in a culture that says, `Go

ahead.' ''

After years of divorce, remarriage and more divorce, half of American

families are stepfamilies. That includes unmarried couples with children

or whose children visit on weekends. Forty percent of her clients, Ms.

Lofas says, don't remarry because they're afraid to commit to another

relationship. Men think they were burned financially in their first

divorce. Women think they got short shrift in theirs.

Children in such homes are wounded from their parents' divorce. Adults

are struggling to find new roles, with each other and new children.

Money must be stretched farther. Previous spouses cause jealousy and

anger among adults, divided loyalties among kids.

``No matter how hard you try, bonding with a stepchild is difficult,''

my friend says. ``My husband's ex-wife made it harder by telling her

daughters never to call me Mom. It's definitely not the Brady Bunch,''

the 1970s sitcom that made blended families look like a bundle of love

and laughs.

My friend is doing her best. If anyone has the intelligence, sensitivity

and determination to succeed as a stepparent, it's her. But I was astonished

to hear her say that if her present marriage ended, which she doesn't

expect, she will not marry again. She would not want her own young child

to grow up in another stepfamily.

Ms. Lofas understands. Society's present problems reflect how kids are

living.

``Children are increasingly unsocialized. Nobody eats dinner together.''

She urges a return to traditional child-raising, to norms and forms,

rules and respect. When she counsels teenagers, she shows them an etiquette

book and says they're welcome to take it. It's the book that finds its

way to their homes most.

Ms. Lofas also does telephone counseling to help parents become better

stepparents. The Stepfamily Foundation is at 333 West End Ave., New

York, N.Y. 10023; her number is (212) 877-3244.

Palm Beach County's child abuse task force needs to examine the role

of stepparenting in abuse and neglect. Have we avoided the issue for

fear of invading people's privacy, just as we shy away from discussing

a related subject, careless conception?

Come on. A lot of kids are in pain. And some will never feel anything

again.

Fran Hathaway is an editorial writer for The Palm Beach Post.

Back To Top

ESTATE OF A.J. SCHWARZ SUES HRS

Sun-Sentinel

May 2, 1995

MIKE FOLKS Staff Writer

The estate of Andrew "A.J." Schwarz filed a lawsuit on Monday

accusing the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services,

the boy's stepmother and his biological father of negligence in his

drowning death.

The wrongful death suit, filed in Palm Beach County Circuit Court, seeks

more than $15,000 in damages on behalf of the 10-year-old's biological

mother, Ilene Soini Schwarz of Fort Lauderdale, his teen-age sister

and half-sister, 5.

On May 2, 1993, A.J.'s naked body was pulled from a 4-foot-deep above-ground

pool at the Lantana-area home he shared with his stepmother, Jessica

Schwarz, and his biological father, David "Bear" Schwarz.

Jessica Schwarz, 40, was convicted last month of first-degree murder

and aggravated child abuse in A.J.'s death.

Jessica Schwarz, already serving 30 years for her convictions last year

on four counts of aggravated child abuse and two counts of felony child

abuse against A.J., faces life in prison when she is sentenced later

this month.

Ted Crespi, the attorney representing A.J.'s estate, said the lawsuit

was filed because HRS officials failed A.J. when he needed them most.

HRS officials "were warned they had a dangerous situation and they

did nothing," Crespi said. "In this case, it's the actions

and inactions of HRS workers that caused the death of this child."

HRS spokeswoman Beth Owen said on Monday that officials with her agency

could not comment until they review the lawsuit.

A.J.'s biological mother, Soini Schwarz, could not be reached for comment

on Monday.

A.J. was placed in the custody of his father and stepmother in 1992

after his biological mother's boyfriend was accused of sexually molesting

his teen-age sister.

The lawsuit says HRS officials should have known A.J. "was the

victim of violent, abusive, neglectful and hazardous care" while

living with David and Jessica Schwarz.

HRS is also accused in the lawsuit of not protecting A.J. by:

-- Failing to report or act upon findings of physical abuse;

-- Failing to complete physical and psychological evaluations on A.J.;

-- Failing to act on abuse and neglect reports filed by A.J.'s neighbors;

-- Placing A.J. in the custody of his father and stepmother, who had

criminal records and pyschological problems.

The lawsuit says David Schwarz breached his duty to care for his son

by failing to protect A.J. from abuse or neglect, which presented a

risk of serious injury or death to the boy.

Jessica Schwarz's negligence was the physical and emotional abuse she

put the boy through. The abuse ranged from forcing A.J. to run naked

through his neighborhood to making the boy trim the lawn with a pair

of scissors, the lawsuit said.

Back To Top

A.J.'S MOTHER FILES LAWSUIT OVER HIS DEATH

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

May 2, 1995

JAY CROFT

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

The biological mother of Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz on Monday filed a wrongful

death suit against the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative

Services, the boy's biological father and the stepmother convicted of

his abuse and murder.

The suit, filed in Palm Beach County Circuit Court, seeks unspecified

damages of at least $115,000.

It names as plaintiff the court-appointed representative of A.J.'s estate,

Theresa Pike, but identifies Ilene Lillian Soini Schwarz and A.J.'s

two half-sisters as surviving beneficiaries able to make a claim on

the estate.

HRS took A.J. from his mother in May 1990 after abuse charges surfaced

against his stepfather. A.J. was placed under HRS protective custody

in August 1990 and sent to live with his father and stepmother in October

1990.

The 10-year-old boy was found dead in the Lake Worth family's pool in

May 1993. His autopsy showed head injuries so severe that they would

have killed him if he had not drowned first.

His stepmother, Jessica Schwarz, was convicted in December of abusing

A.J. and on April 11 of murdering him.

Besides Jessica Schwarz, the other defendants named in the suit are

the state, HRS, HRS Secretary James Towey, ex-Secretary Robert Williams,

various HRS supervisors and employees and A.J.'s father, David A. Schwarz.

Barbara Black, the HRS investigator assigned to A.J.'s case before his

death, is among the defendants. She was indicted in December 1993 on

a charge of extortion by threat for allegedly telling a neighbor she

would lose her children if she continued calling HRS about A.J.'s abuse.

A judge in March agreed to privately review a grand jury note explaining

why Black was indicted one month after a prosecutor said she would not

be charged.

Back To Top

AROUND TOWN

The Palm Beach Post

May 6, 1995

Show will feature A.J.'s mom

Jessica Schwarz, the first mother convicted in a recent string of parent-child

murder cases, will be featured on an upcoming Maury Povich show, publicist

Gary Rosen said Friday. Schwarz was convicted of second-degree murder

this year in the death of her stepson, A.J. A crew from the show will

interview Schwarz at the county stockade Monday, taping a satellite

feed to the New York-based show from 7:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. The crew

also will interview Ileen Schwarz, A.J.'s mother. The 10-year-old boy

was found floating in Jessica Schwarz's pool in May 1993. On Monday,

Ileen Schwarz filed a wrongful death suit against the state Department

of Health and Rehabilitative Services, which took custody of A.J. when

he was 8 and placed him with Jessica Schwarz. No date has been set for

airing the broadcast, Rosen said. - Jenny Staletovich

Back To Top

PROSECUTORS IN CHILD DEATHS TRY TO STAY DETACHED

Sun-Sentinel

May 8, 1995

STEPHANIE SMITH Staff Writer

In the hierarchy of the prosecutorial profession, a prosecutor specializing

in crimes against children was in the lower rungs, considered something

of a social worker with a law degree.

There was little glamour and even less glory in pleading out and putting

away child molesters and child beaters day in and day out. The prosecutors

who made the headlines and the nightly news were the ones handling major

crimes, homicides.

Then came a series of wrenching child killings in Palm Beach County.

The little-known Crimes Against Children division was propelled into

the spotlight two years ago after the drowning that ended 10-year-old

A.J. Schwarz's tortuous short life.

Then the killings came faster and more furious. Christina Holt, Kayla

Bassante, Dayton Boykin, Pauline Cone, Tiffany Greenfield and Charles

Mejia.

The division's chief, Assistant State Attorney Scott Cupp, fields telephone

calls from law school students who want to know how they, too, can represent

children.

Cupp is quick to correct them.

"I try to keep in mind to the attorneys who do this, we don't represent

the children, we represent the State of Florida. I'm not a social worker,"

Cupp said. "These kids have enough people wringing their hands,

feeling sorry for them. We're here to prosecute these cases."

He does not consider himself a champion of children, a social reformer,

and he doesn't want such zealots on his staff, Cupp said.

"They want to do social work, they want to get touchy, feely with

the kids," he said of the social-worker types. "When the case

is over, you're not going to see them again. It's not fair to the kids.

Like everything else that's happened to them, you let them down."

Cupp has specialized in crimes against children for six years, almost

a record in the field. The work is usually so depressing and emotionally

consuming, most prosecutors beg to be transferred out or are rotated

out by their bosses within two years.

Cupp maintains both a passion and detachment for the work, his employees

and bosses said.

But Cupp's cool, professional demeanor drops when he talks about the

Schwarz case. His eyes glisten and his voice nearly chokes.

"It was difficult not to identify with the kid, once you started

to see what he went through. I think the hardest part was the constant

realization of how trapped he really was," Cupp said.

Andrew J. Schwarz's naked and bruised body was found floating in an

above-ground swimming pool. Neighbors testified the boy was literally

tortured by his stepmother for years. He was assigned demeaning chores

such as cleaning after the dog, forced to eat a cockroach and made to

wear a T-shirt that proclaimed he was worthless.

Cupp and co-prosecutor Joseph Marx openly cried when A.J.'s stepmother

Jessica Schwarz was convicted in September on six counts of child abuse.

In a separate trial, Schwarz was convicted in April of drowning her

stepson.

Marx said the case was the most important one in his life.

That Marx was able to go on, to take the case to trial in September,

just two and a half months after the killing of his wife was evidence

of his commitment.

Karen Starr Marx, 30, was four months pregnant with their first child

when she was shot to death on May 27. The killing made headlines because

it was during a meeting to take a deposition for a lawsuit in Fort Lauderdale.

Karen Marx, a civil lawyer, was at the deposition because a colleague

at her Palm Beach law firm couldn't make it.

A disgruntled former employee opened fire on his ex-boss, and the lawyers

were caught in the middle. Clarence L. Rudolph, who ran a job placement

service for senior citizens, also was killed.

Marx said his wife would have wanted him to follow through with the

Schwarz case. His wife helped him prepare the case and write legal briefs.

"She really said to me, `Joe, you better get her.' She hated that

woman with a passion. She'd cry about what happened to this boy,"

Marx said.

Schwarz was Marx's last trial as a prosecutor in the division for crimes

against children.

"When my wife died, those cases required so much emotional energy,

I just couldn't do it any more," Marx said.

Now he is in the official corruption unit, at his request. His latest

big case was the grand jury investigation into the prison escape at

Glades Correctional Institution in Belle Glade.

Marx says he was a touchy-feely kind of prosecutor who took children

to McDonald's and tried to solve every problem until it wore him down.

"You're more open to it in there, to burn yourself out," Marx

said. "Sometimes you have to be a little cold to it. You have to

keep your distance to a certain extent. These people will wear you out

if you let them because they want you to fix everything and you want

to fix it for them."

He wants to go back to the division, but when he's emotionally ready

and maybe a bit more detached.

"It was the most worthwhile thing I've ever done," Marx said.

Back To Top

WHEN CHILDREN DIE

The Palm Beach Post

June 2, 1995

Pauline Zile's child died in her presence. Zile may go to the electric

chair. Paulette and Timothy Cone's child died in their presence. The

Cones were convicted of only a misdemeanor.

With a Palm Beach County jury having decided last week - after much

debate - that the Cones were not directly response for the death of

their 2 1/2-year-old adopted daughter, Pauline, it's a good time to

evaluate just how the criminal-justice system is handling the tragically

high number of cases in which children died. Three have been decided.

Sadly, we're barely halfway. And investigations may turn up more.

First was Jessica Schwarz. She was convicted of second-degree murder

in the death of her stepson, A.J., found floating in his backyard pool.

Next came Zile, who was found guilty of first-degree murder in the death

of her daughter, 8-year-old Christina Holt, and will be sentenced this

month. The Cones were indicted on first-degree murder charges after

a plywood lid on Pauline Cone's crib slammed shut and killed her. Prosecutors

alleged that the Cones committed aggravated child abuse, which is a

felony. Under Florida law, commission of a felony that results in death

makes someone eligible for a first-degree murder conviction.

Still to come are:

Clover Boykin. She was indicted on two counts of first-degree murder

last year for allegedly strangling her 5-month-old son and a friend's

8-month-old daughter whom she was babysitting.

Joanne Mejia. She is also charged with first-degree murder in the January

death of her son, 4-month-old Charles Joe Mejia.

Jacqueline Caruncho. She was indicted on third-degree murder and felony

child abuse charges in the December death of 4-month-old Tiffany Greenfield.

If convicted, she could get 20 years. Prosecutors believe that both

the Mejia and Caruncho cases involve shaken baby syndrome.

All such cases are ``problematic,'' said a spokesman for State Attorney

Barry Krischer. That's an understatement. Even the best system will

have trouble responding consistently to something as tragic as the deaths

of children. It may be tempting, given the Cones' comments about what

they had to endure, to say that prosecutors should back off. But the

Cones were found guilty of negligence. And jurors said nearly half the

12-member panel had argued for a murder conviction.

Mr. Krischer, who is up for election next year, will be seen as trying

to score political points by going after child-killers. But his office

has correctly given more attention to all domestic violence than did

the previous administration. And the public, which hands up indictments

and renders justice, seems able to distinguish not only between criminal

parents (such as Zile) and troubled parents (such as the Cones) but

between degrees of criminality. Witness the different indictments for

Schwarz, Mejia and Caruncho.

It wouldn't hurt Mr. Krischer to remind his prosecutors of the difference

between dedication and zealotry. But those prosecutors are speaking

up in death for children who had no one to speak up for them in life.

Back To Top

NEW SCHWARZ TRIAL SOUGHT

Sun-Sentinel

June 10, 1995

Staff Report

Jessica Schwarz, who faces life in prison for killing her 10-year-old

stepson, A.J., should get a new trial because she was convicted on circumstantial

evidence, her defense attorney argued on Friday.

Defense attorney Rendell Brown argued in Palm Beach County Circuit Court

on Friday that the state failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that

Schwarz drowned A.J. in the family's backyard pool in May 1993.

Brown said the state failed to disprove defense theories that A.J. could

have drowned while snorkeling in the nude in the pool or hit his head

on the edge while taking a midnight swim.

In addition, Brown said Circuit Judge Karen L. Martin erred when she

considered abuse evidence that surfaced during Schwarz's August trial,

which resulted in her conviction and a prison sentence of 30 years.

The abuse ranged from Schwarz forcing the boy to run nude through his

neighborhood to forcing him to eat from a dog bowl on the floor.

But Prosecutor Joe Marx argued that the judge, who presided over Schwarz's

non-jury trial, found the testimony and evidence credible enough to

convict in the boy's slaying.

Martin, who is scheduled to sentence Schwarz on the second-degree murder

conviction on July 28, said on Friday that she will issue a written

ruling on the new trial request in the next few weeks.

Back To Top