Home --> AJ's Story --> AJ's Story: Newspaper Articles --> 1995 Page 1

A.J.'s Story

- Newspaper Articles

The following links take you to various articles in AJ's story as it

appeared in the South Florida media.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE INFORMATION ON THIS SITE BEFORE ASKING.

Thank you!

|

|

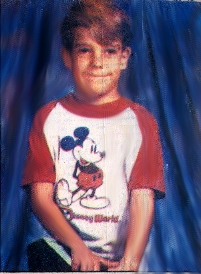

In Loving Memory Of Andrew James "A.J." Schwarz April 24,1983 - May 2,1993 "Beautiful Child who has found love from the angels...RIP..." |

|

This

page contains articles from the Palm Beach Post and The Sun-Sentinel

from the year 1995. |

|

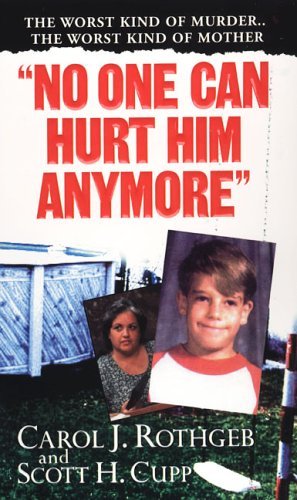

If you are interested in reading the FULL DETAILS of this case aside from what is posted here, please purchase "No One Can Hurt Him Anymore" by Carol J.Rothgeb and Scott H. Cupp. Mr. Cupp thinks it's the book that nobody will read...please show your support and show him that you care about AJ, too by ordering his book by clicking on the cover image below.

Person of the Year: Christina Holt (1/1/95)

Task Force Taking Closer Look at HRS (1/9/95)

Uncle Sam May Not be Such A Bad Babysitter (1/12/95)

Grand Jury: HRS Failed Kids

Indicting Performance of HRS is Just Too Easy (1/19/95)

In Court (1/24/95)

HRS Panel Criticizes Rebuke (1/28/95)

Lawyers Aren't Only Problem (1/29/95)

In Court (2/28/95)

Judge To Review Indictment in HRS Case (3/14/95)

Some Abuse Evidence Allowed in Schwarz Murder Trial (3/18/95)

PERSON OF THE YEAR:

CHRISTINA HOLT

The Palm Beach Post

January 1, 1995

FRAN HATHAWAY

It was the year of the child. The dead child.

It was the year South Floridians realized that the most dangerous place

for children is not in the streets or the malls or the schools but at

home - with their parents.

Consider these snapshots from 1994's grisly scrapbook.

Snap! Oct. 22.

A distraught Pauline Yingling Zile runs from a restroom at a Broward

County flea market, shouting that her daughter is missing. But 7-year-old

Christina Holt is dead, beaten to death five days earlier by her stepfather,

John Zile. He confesses to stuffing the child's body in a closet of

their Riviera Beach apartment for four days before burying her near

a Tequesta shopping center. Charged with first-degree murder, Pauline

and John Zile may face the death penalty if convicted.

Snap! Oct. 27.

Clover Boykin, 19, of Royal Palm Beach kills her 5-month-old son, Dayton.

She also confesses to killing 9-month-old Kayla Basante in November

1993 while baby-sitting the child. Clover Boykin is indicted on two

counts of murder.

Snap! Nov. 10.

Pauline Cone, 2, dies when a wooden lid rigged to her crib slams shut

and strangles her. Adoptive parents Paulette and Timothy Cone of Lake

Worth are charged with first-degree murder and child abuse. They had

earned $65,000 as foster parents while caring for 43 children during

a four-year period, despite numerous police calls to their home.

Snap! Nov. 26.

Sasha ``Sassy'' Gibbons, 4, dies at a Broward County hospital four days

after Carlos Schenk spanks her for cursing at him, hits her with a belt

when she doesn't stop, pours hot sauce in her mouth, wraps her in a

comforter and wedges her under a waterbed mattress in their Pompano

Beach home. Schenk, fiance of Sassy's mother, Rebecka Gibbons, is charged

with first-degree murder.

Snap! Dec. 10.

Blowzy, brutal Jessica Schwarz is sentenced to 30 years in prison for

abusing her 10-year-old stepson, A.J. He was found dead in the family's

backyard pool in May 1993. The Lantana woman still must stand trial

on murder charges in his killing.

All of these deaths stunned South Florida - especially because they

involved people who should have been protecting the children. But it

was Christina who crystallized the horror.

Within days of that shock, public outrage was compounded by an eerily

similar tale told by a 23-year-old South Carolina secretary named Susan

Smith. On Oct. 25, Ms. Smith tearfully claimed that her sons - Michael,

3, and Alex, 14 months - had been abducted by a carjacker. On Nov. 3,

the boys' decomposing bodies were found in their mother's car in a lake

near the small mill town of Union. Ms. Smith, who came from what townspeople

called ``a good family,'' will stand trial on murder charges.

Before closing the album, consider one more picture.

Snap! June 17.

Ever-smiling celebrity ex-jock O.J. Simpson is arrested on charges of

killing his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ronald Goldman.

The couple's two young children were asleep inside Ms. Simpson's townhouse

when their mother was slashed to death, her head nearly severed from

her body. Emergency 911 tapes later indicate that Nicole Simpson was

a battered wife.

We call such spousal beating domestic abuse. We call parental battery

on children child abuse. Increasingly, however, we describe it all as

family violence.

Each year, The Post selects a Person of the Year, someone who has had

a major impact on Palm Beach County and the Treasure Coast. For 1994,

The Post's Person of the Year is Christina Holt, a child who in death

represents all the children who are brutalized by those they trusted.

In 1994, no issue shocked and angered us more than the deaths of children

at the hands of their parents.

Abuse - physical, emotional, sexual - does more than warp children's

lives. It endangers society when kids who live with violence act out

that violence on others. Last year, a tide of kids with few morals and

little hope crested in a wave of juvenile crime that would have been

unthinkable earlier. In one 13-month period, Florida saw 10 fatal attacks

on foreign visitors, most by teenagers.

The 1994 legislature responded by passing a $237 million reform of the

juvenile-justice system that created a Department of Juvenile Justice.

Gov. Chiles called it a balance of prevention, early intervention and

detention. But the emphasis was punitive.

Few children are born bad. It's just that more and more are born to

people who conceive them ``accidentally'' and don't give a damn about

raising them. These adults are the criminals, and preventing more like

them is essential. The 1994 Person of the Year reminds us that child

abuse sows the seeds of our own destruction.

We live what we learn. Children who grow up in violent households are

likely to become offenders themselves. Palm Beach County State Attorney

Barry Krischer wants the law to help break this cycle. In December,

he told local legislators that beating a spouse in front of a child

should be considered child abuse, punishable by up to five years in

prison. He's right. Children who witness a mother being beaten may be

as traumatized as if they were being beaten themselves.

If performing sexual acts in front of children is a felony - which under

state law it is - violence in front of kids should be, too. The increase

in child-on-child sexual abuse - kids as young as pre-schoolers acting

out sex acts on other children - tells us that children are either seeing

those acts in their own homes or are being molested.

Abuse takes another form - neglect - that seems less deadly. But neglected

children shrivel psychologically and physically. Neglected babies may

fail to thrive. Being home alone isn't funny after all.

And it's getting worse. Social workers say that what outraged them 20

years ago seems almost tame compared with behaviors often leavened by

drugs, alcohol and pornographic material.

At the same time, some parents insist that they have a right to discipline

their children by hitting them. Even some lawmakers see nothing wrong

with violence as punishment. Last spring, the legislature passed a bill

intended to ``restore parental authority'' by allowing parents to spank

their children on public property. (When child advocates said the bill's

definition of what constitutes abuse was not appropriate, Gov. Chiles

vetoed it.)

One lawmaker who sees a great deal wrong with violence as punishment

is incoming Rep. Lois Frankel, D-West Palm Beach. As the expected chairwoman

of the House Select Committee on Child Abuse, Ms. Frankel has both the

will and the way to propose better ways of protecting all citizens from

abuse.

She should get some help from two new local groups. Palm Beach County's

Domestic Violence Council was formed after the Simpson case heightened

awareness of spouse abuse. And beginning in January, a countywide task

force formed by the Florida Department of Health and Rehabilitative

Services will review Palm Beach County's child protection system.

But we all have a responsibility to report signs and sounds of violence

coming from someone's home. When people do call the state abuse registry,

HRS has a responsibility to make sure calls are evaluated properly and

investigated promptly by local officials. In the A.J. Schwarz case,

a Lantana neighbor called HRS to report that Jessica Schwarz beat her

stepson and smoked crack cocaine. An HRS worker threatened to take the

neighbor's children if she didn't stop calling. A grand jury report

sa id A.J. might have been saved if HRS had done its job properly.

Sometimes, however, HRS doesn't even get the chance. In the Christina

Holt case, Riviera Beach neighbors of John and Pauline Zile heard screams

and sounds of beatings and did nothing. A friend of John Zile's saw

him beat Christina with a belt but did not call HRS, as required by

law.

Violence behind closed doors is no longer a ``private matter.'' Anyone

in doubt about calling HRS should remember this message from the Family

Violence Prevention Fund: ``If the noise coming from next door were

loud music, you'd do something about it.''

Fran Hathaway is an editorial writer for The Palm Beach Post.

Back To Top

TASK FORCE TAKING CLOSER LOOK AT HRS

The Palm Beach Post

January 9, 1995

SCOTT SHIFREL

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

The state's 24 protective services workers in Palm Beach County keep

an eye on 35 families each, more than twice the recommended standard.

The average salary for an entry-level counselor in the state's children

and family division is between $20,000 and $33,000 a year.

And local Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services officials

can't increase the pay scale or add workers without the Florida Legislature's

approval.

Such limitations are among those to be discussed Tuesday by the first

meeting of a task force of local officials concerned with child welfare.

The group - which includes Rep. Lois Frankel, D-West Palm Beach, schools

Superintendent Monica Uhlhorn, West Palm Beach Police Chief Billy Riggs

and others - is the idea of HRS District Administrator Suzanne Turner.

Spurred by a recent spate of highly publicized child-abuse cases, she

hopes it will explain what HRS does to those who need to work with the

system.

The state agency has been criticized for its handling of some of those

cases, including the deaths of 10-year-old Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz,

7-year-old Christina Holt and 2-year-old Pauline Cone.

In the most recent case, poor communication was partially blamed for

a situation that led to Pauline's death in a foster home. HRS was unaware

that domestic problems had been reported numerous times to police.

The task force is aimed at bridging the communications gap and coming

up with solutions by including law enforcement officials, judges, attorneys

and child-welfare advocates.

``This is probably the first time this group has worked together,''

Turner said. ``The goal is for us to have the strongest protection system

possible.''

She also hopes it comes up with ammunition for HRS officials to take

to the March legislative session, which promises to focus on the state

agency.

The focus of the group will be protective investigations, child protection,

foster care and adoption. Turner hopes eventually to have national and

local experts on these subjects give presentations.

A packet prepared for the task force's first meeting Tuesday details

some of the limitations state officials run into while trying to protect

children.

Besides the low salaries and high workloads - problems that have been

discussed for years - the packet reviews:

The lengthy process it takes for HRS to remove a child from a home.

The criteria for child abuse to be reported into the state hot line.

The limited budget of the children and families division of HRS.

The qualifications for protective services workers.

Tuesday's gathering will be an organizational meeting with the 16 officials.

Turner said she hopes they agree to meet several more times before the

March legislative session.

``We're trying to educate the community about what we are, about what

our shortcomings are and where we can get help,'' she said.

Back To Top

UNCLE SAM MAY NOT BE SUCH A BAD BABY SITTER

The Palm Beach Post

January 12, 1995

RON WIGGINS

Something government does well: Child-rearing.

You doubt?

A Manhattan psychiatrist who runs a residential-care center for ``adolescents

no one else will take'' says the government often does a better job

of rearing children than some parents. Certainly A.J. Schwarz, Christina

Holt and Susan Smith's children are not around to disagree.

So why, asks Dr. Michael A. Pawel, do we treat institutional caregivers

as though they were wicked stepmothers?

Pawel's essay in the January The Humanist does such a good job of addressing

the issue of institutional care that I called him at the August Aichhorn

Center for Adolescent Residential Care, where he is executive director.

Q: Dr. Pawel, could you expand on your statement that ``Institutional

care can be a good thing, and it could be even better if the resources

devoted to attacking it were instead used to improve it.''

A: Clearly institutional care is a last resort and I certainly agree

that the nuclear family is the best child-rearing environment. The fact

is, those families are not available to all who need them, and when

the foster-care system fails, you reach a point where congregate care

is the only option available.

Q: Are you succeeding where the original parents and the foster-care

system failed?

A: In spite of the system, in spite of the fact that we start with physically

destructive, severely disturbed adolescents, all with histories of abuse

or sexual abuse, we do amazingly well.

Q: By what standard?

A: Instead of loading up the prison system, we have mainstreamed some

into the: public schools, a few into job training, two want to go to

college, and others have gone back to their families.

Q: How do you instill moral values when the state cannot ``preach''?

A: The kids we have, 13 and 14, are at the kindergarten level in terms

of behavior. We keep it very simple and very clear: no violence, no

stealing, treat others as you would like to be treated. Our youngsters

have not had a close relation with adults, and we are able to give them

that.

Q: And for this, you are seen as wicked stepmothers?

A: This is the main thing I would change, the belief that child-care

workers are engaged in the lowest skill work available. The salary and

social status of these jobs speaks to that. Would you want your kid

to grow up to be a child-care worker? It is amazing to me the good job

most of these people do with no recognition.

Q: Will state orphanages spring up if mothers are taken off welfare?

A: I don't think so. I think we'll see hostels where both mother and

child can stay for a while. Let the mothers cook, get some parenting

skills and look for a job. In effect, we'll say, ``We'll watch the baby

while you look for work.''

Q: Be it so humble, there's no place like . . .?

A: Institutional care? In our case, yes, when you consider that like

the average respectable family, we don't throw anyone out.''

Back To Top

GRAND JURY: HRS FAILED KIDS

The Palm Beach Post

January 14, 1995

JENNY STALETOVICH

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

The state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services has tragically

failed in its mission to protect children, a grand jury concluded Friday

in a scathing report after questioning the agency's top administrator.

In fact, children who turn to the agency for help risk suffering even

more abuse, the report said.

``It is clear that the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services

is not adequately protecting children in Palm Beach County and appears

to be unable to make the changes necessary to protect children,'' the

report said. ``Children . . . are at significant risk for further abuse

if they are taken into (HRS) custody.''

Jurors made their findings after reviewing the deaths of four children

and charging their parents or guardians with murder.

In the past few months, jurors have questioned police investigators,

HRS officials, foster parents, therapists and school officials in the

deaths of 7-year-old Christina Holt; Dayton Boykin, 5 months; Kayla

Basante, 8 months and Pauline Cone, 2. On Friday, they ended their investigation

by questioning HRS Secretary Jim Towey for more than an hour, then questioning

District Administrator Suzanne Turner.

``I got a good earful from people who really care about children,''

Towey said after appearing by invitation before the grand jury. ``We

can do better and we must do better.''

Jurors have asked the agency to respond to the report, but HRS officials

are not required to by law.

Both Towey and Turner said they have not decided how they will answer

the review. Many of the recommendations would require changing state

law and spending more money, Turner said.

``We do help thousands of individuals and do save lives,'' she said.

``The unfortunate thing is we keep coming up with new ideas. We have

the issues of foster care versus orphanages and state hot lines versus

local hot lines and law enforcement doing investigations versus us.

It doesn't matter who's doing it if the resources aren't there.''

Jurors based many of their findings on the case of Pauline Cone, a crack

baby seized by HRS and placed with a Lake Worth foster couple whose

troubled past included a shooting conviction, psychiatric evaluations

and drunken driving.

Pauline died Nov. 10 after a lid Timothy and Paulette Cone rigged to

her crib slammed shut and strangled her, the medical examiner's office

found.

Jurors charged the Cones with felony murder and aggravated child abuse,

saying they illegally caged her. Jurors also charged the couple with

caging a second adopted daughter and abusing an 18-year-old foster daughter.

After licensing the Cones as foster parents in January 1991, the agency

placed 43 children in their home, paying them more than $65,000 through

September 1994.

Records show the agency was warned about problems in the home weeks

before Pauline died but found nothing wrong. Officials knew but were

not worried about Paulette Cone's 1979 conviction for shooting a man.

Lake Worth police also visited the house repeatedly for fights and neighbor

disputes during the three years the Cones provided foster and emergency

shelter care.

In reviewing the agency, jurors found faults in administrative procedures

and in the very workings of child abuse investigations. Some of those

findings include:

Workers, who respond too slowly to abuse complaints, don't provide immediate

protection for children in danger.

Delays on an abuse hot line make it useless.

Agency investigators and attorneys are not qualified to handle child

abuse complaints and court proceedings.

Background checks into foster homes are inadequate, putting children

in danger.

Foster parents are allowed to spend HRS money without having to account

for it.

Workers don't share information.

Jurors also found that the agency ignored a critical report issued in

December 1993 after 10-year-old Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz died. After

a grand jury charged his stepmother with murder, they found agency workers

cared more about closing cases than protecting children. The panel asked

for a centralized filing system and that police take over investigations.

Turner said the agency is working to get computerized records and has

struggled to work more closely with police.

On Friday, jurors recommended overhauling major areas of the agency.

Again, they insisted police take over child abuse investigations. They

also suggested the state attorney's office handle court proceedings.

The abuse hot line should be abandoned, and a new one established and

run locally like the county's 911 system. State laws should be revised

to put police in charge of children's safety in emergency situations

and investigations. HRS should be limited to children's services.

Jurors also asked that a statewide grand jury be impaneled to collect

critical reports about the agency from around the state and investigate

the agency's operations.

Copies of Friday's report will be sent to Gov. Lawton Chiles, Towey,

various elected officials, the statewide prosecutor and all state attorneys.

KIDS AT RISK

It is clear that the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services

is not adequately protecting children in Palm Beach County and appears

to be unable to make the changes necessary to protect children. Children

. . . are at significant risk for further abuse if they are taken into

(HRS') custody.'

- GRAND JURY REPORT

FOR HRS, A SYSTEM CHECK

After reviewing the death of 2-year-old Pauline Cone and three other

children, grand jurors found the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative

Services tragically fails to protect children. They found other problems

with the agency and suggested changes. Some are:

FINDINGS:

CRIMINAL abuse investigations are hampered by the agency's delay or

failure in reporting abuse complaints.

DELAYS in the abuse hot line discourage the public from making complaints.

INSUFFICIENT background checks are done on foster families.

FOSTER parents are not required to account for how they spend the money

HRS gives them.

AGENCY officials fail to share information.

THERE are no rewards for good workers nor penalties for those who fail

to do their jobs.

AGENCY attorneys are not qualified to handle cases.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

SET UP a new, local abuse hot line.

WHEN licensing foster families, check with local police, fire and health

departments. Interview neighbors, teachers and professionals who deal

with the family and complete local, state and federal criminal background

checks.

ACCOUNT for HRS money spent by foster families.

CHANGE state laws to put police in charge of children's safety in emergency

situations and investigate abuse. Limit HRS to providing social services.

CREATE a central filing system.

MAKE recommendations from the Child Protection Team binding.

TURN over court proceedings on dependency cases to the state attorney's

office.

Back To Top

INDICTING PERFORMANCE OF HRS IS JUST TOO EASY

The Palm Beach Post

January 19, 1995

Here is what can happen when the Department of Health and Rehabilitative

Services investigates child abuse in Palm Beach County:

A worker in Belle Glade was checking out reports about a potentially

abusive father. The father showed up at her home. Fortunately, nothing

happened. Another investigator was in a home when a young man high on

PCP, a hallucinogenic drug, put his hands around her neck. Luckily,

the boy's father stopped him. Far more often, workers go into homes

where crack cocaine is smoked, causing the parents to become extremely

violent. (``Hi. Mind if I ask some questions to find out whether you're

beating your kids?'')

It in this context that we must consider last week's report by a Palm

Beach County grand jury that ``children alleged to be abused, neglected

or abandoned in Palm Beach County are at significant risk for further

abuse if they are taken into the custody of the Department of Health

and Rehabilitative Services.'' The grand jury examined HRS itself after

issuing indictments against ``two biological mothers (Pauline Zile and

Clover Boykin), one step-father (John Zile) and a foster-care couple

(Paule tte and Timothy Cone).'' The Ziles were indicted on murder charges

in the death of their daughter, Christina Holt; Boykin for allegedly

killing her own baby and another infant; the Cones in the death of their

adopted daughter, Pauline.

The grand jury said, in effect, that when it comes to child protection,

HRS doesn't work. That was true when it came to these four children.

And it is true that HRS has too often blamed problems on money, not

its own bad decisions. It is also true, however, that HRS gets no points

for success. Reunited families or children who get new, good homes are

like airplane flights that land safely. Only crashes get noticed.

But since the grand jury report included several recommendations, and

since two task forces are also looking into HRS' performance, and since

a misguided but regrettably influential state senator has asked HRS

to figure how the agency would cut $1 billion from its budget and do

good work, let's keep our minds on one question: How well can any system

work under the burden of too much work, too little money and too many

rules?

For example, the grand jury concluded that HRS can't reward good employees

or fire bad ones - such as the supervisor in the A.J. Schwarz case who

dithered until the 10-year-old Lantana boy was found dead in his pool.

(His stepmother, already convicted of abuse, faces murder charges.)

The people who actually conduct investigations and make decisions about

removing children from homes have to move into administration or leave

to get better pay. The grand jury also mentioned ``employee turnover

and low morale.''

Guess what? HRS officials under Republican and Democratic governors

have made the same complaints to the legislature for years. The response?

The legislature has made little effort to change rules about hiring,

firing and pay. The legislature has refused to provide enough money

to run a good foster-care program, leading to a lawsuit that could result

in federal sanctions.

So before we tear apart HRS' child-protection system, we ought to decide

how much of the problem is HRS and how much is the ``system'' HRS has

been given. Rather than turn over all child-protection duties to police

agencies, what if the legislature allowed the agency to hire, fire,

promote and demote at will? Rather than ask HRS to cut $1 billion, what

if HRS was given more money and could, as the grand jury recommended,

``pay wages commensurate to the position?'' (Investigators start a t

about $22,000; teachers get $27,000.) Rather than the legislature sending

orders, what if local HRS districts could set rules, as Palm Beach County's

HRS board has asked to do?

Finally, any ``perfect'' system will fail sometimes. Our homes have

too many guns, too many drugs and too little parental responsibility.

We can change agencies all we want, but we won't make real progress

until we change ourselves.

Back To Top

IN COURT

The Palm Beach Post

January 24, 1995

WEST PALM BEACH

The attorney representing Jessica Schwarz on a second-degree murder

charge said he would prefer pleading her case to a judge instead of

a jury if the trial is in Palm Beach County. Rendell Brown said publicity

surrounding Schwarz's earlier trial and conviction on child abuse charges

in the treatment of her stepson, Andrew, ``A.J.'' Schwarz, makes it

unlikely an impartial jury could be found to hear the murder case. A.J.,

10, was found in his family's backyard pool in Lake Worth May 2, 1993.

Autopsy reports showed head injuries so severe that had he not drowned,

he would have died from the blows. Prosecutor Scott Cupp said his office

probably will oppose Brown's request, filed Monday, to try Schwarz,

39, without a jury. In that case, Brown said, he'll ask that the trial

be moved out of Palm Beach County.

Back To Top

HRS PANEL CRITICIZES REBUKE

The Palm Beach Post

January 28, 1995

SCOTT SHIFREL

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

A grand jury report criticizing the way the state protects children

was called ``irresponsible and untruthful'' Friday by the board overseeing

the county's main social service agency.

The report was misleading and unfounded, said the local board for the

state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services.

``There must be an obligation to the truth,'' Health and Human Services

Board Chairman Joseph Orr said in a statement. ``To link HRS with each

of the four children cited in the report was irresponsible and untruthful.''

Up to now, HRS officials have been restrained in their criticism of

the report, issued Jan. 13 after jurors reviewed the deaths of four

children and charged their parents or guardians with murder.

Those cases included the deaths of Christina Holt, 7; Dayton Boykin,

5 months; Kayla Basante, 8 months; and Pauline Cone, 2.

Pauline was the only one of those children who had been taken away from

her parents by HRS, but the jury concluded that children ``are at significant

risk for further abuse if they are taken into (HRS) custody.''

The Health and Human Services Board blasted that conclusion.

``To state that children risk further harm once in our custody lacks

knowledge of the system, its responsibilities and limitations,'' Orr

said.

But the grand jury, which spent months questioning police investigators,

HRS officials, foster parents, therapists and school officials, based

many of its conclusions on the Cone case.

Records show HRS knew or should have known about problems at the home.

Jurors also found that HRS officials ignored a critical report issued

in 1993 after the death of 10-year-old Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz, who

also had been taken into HRS custody.

Andrew's stepmother has been charged with murder in his death.

The jury said the state should make major overhauls, but board members

said changes are not possible without help from state legislators.

``I think we have an organization trying to do the best job we can with

very, very limited resources,'' said Sally Chester, board vice chairwoman.

The board scheduled a meeting to discuss the report with the community

at 1:30 p.m. Feb. 7 at the Palm Beach County Children's Services Council

at 111 S. Dixie Highway, West Palm Beach.

Back To Top

LAWYERS AREN'T ONLY PROBLEM

Sun-Sentinel

January 29, 1995

DEBBIE CENZIPER and SHERRI WINSTON

Staff Writers

You can't just blame the lawyers when abused kids are left unprotected

by the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services.

Before an abuse case ever goes to court, before an HRS attorney ever

gets involved, agency investigators and social workers on the front

lines of child welfare cases must detect and document abuse so the attorneys

can prove a young life is at risk.

But sometimes, child advocates and legal experts say, those investigations

aren't done right.

HRS investigators and counselors are not trained police officers, critics

say, and often don't know what type of evidence or witness it's going

to take to prove a case. And with heavy caseloads, salaries hovering

at about $20,000 and high turnover rates, the workers don't always stick

around long enough to do the proper digging.

HRS attorneys may be the latest group of employees at the state agency

to come under siege, accused of being ill-equipped to handle legal proceedings,

but HRS investigators and social workers have long been chastised for

tripping up on the job.

"The attorneys are only as good as the information that comes to

them," said Palm Beach County Juvenile Court Judge Howard Berman.

"Unless the attorneys go out and do their own investigations, they

are sitting in their office and reviewing the reports. That's all they

have to go on. And legally, I have found there has been a lot lacking

with the investigations."

Last August, more than 18 neighbors testified they witnessed Lantana

resident Jessica Schwarz abuse her 10-year-old stepson. But two HRS

caseworkers said they never suspected the child was in danger, even

after visits to his home and school.

Stepmother Jessica Schwarz was convicted of A.J.'s murder.

In another case in September 1993, 8-year-old Joseph Bellamy won a $14.5

million judgment against HRS in Broward County. Joseph had been thrown

against a wall by his mother when he was 4 months old and repeatedly

shaken until his brain was permanently damaged. Despite complaints from

eight tipsters, HRS caseworkers allowed the infant to stay with his

parents, who were mentally ill.

"Some cases get investigated and they are never brought to the

legal system; the attorneys don't even know about those cases,"

said Amy Hickman, a former HRS attorney who now works for the Legal

Aid Society. "Kids fall through the cracks without the lawyers

ever getting involved."

Back To Top

IN COURT

The Palm Beach Post

February 28, 1995

WEST PALM BEACH - A construction company filed papers Monday in circuit

court to foreclose on the Lake Worth home of David and Jessica Schwarz,

whose 10-year-old son, A.J., was killed in May 1993. Jessica Schwarz

was found guilty of abusing A.J. and was sentenced in December to 30

years in prison. She still must stand trial on second-degree murder

charges in the boy's death. Norman Construction Inc., claims the Schwarzes

have not made payments on the $66,400 mortgage for their house at 5881

Triphammer Road in Lake Worth since August.

Back To Top

JUDGE TO REVIEW INDICTMENT IN HRS CASE

The Palm Beach Post

March 14, 1995

A judge will privately review a grand jury note that explains why an

indictment was filed against a caseworker for the Department of Health

and Rehabilitative Services one month after a prosecutor said she would

not be charged.

An attorney for Barbara Black asked Circuit Judge Marvin U. Mounts Jr.

on Monday to dismiss a charge of extortion by threat against Black,

saying the grand jury issued the indictment in response to media reaction

to its earlier decision not to indict HRS officials connected to the

A.J. Schwarz case.

Schwarz, 10, was found dead in his family's pool. His stepmother has

been charged with second-degree murder. Black allegedly vowed to take

away the children of a witness in the case who repeatedly called HRS

and reported that Schwarz was being abused.

Back To Top

SOME ABUSE EVIDENCE ALLOWED IN SCHWARZ MURDER TRIAL

Palm Beach Post, The (FL)

March 18, 1995

JAY CROFT

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Prosecutors will be allowed to use part of Jessica Schwarz's child-abuse

conviction in their murder case against her next week, a judge ruled

Friday.

Schwarz was found guilty in December of abusing her 10-year-old stepson,

Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz. A judge called the abuse ``barbaric and grotesque''

and sentenced her to 30 years.

A.J. was found dead in the Lake Worth family's pool in May 1993. The

autopsy showed head injuries so severe that had he not drowned, he would

have died from the blows.

Jessica Schwarz faces second-degree murder charges. Her non-jury trial

begins Monday.

Prosecutors may not use in court the fact that she rubbed the boy's

face in his urine-soaked bed sheets. That was one of six child-abuse

counts of which she was found guilty.

The state also won't be able to use charges that she kept the boy home

from school as punishment or forced him to trim the lawn with scissors.

Circuit Judge Karen Martin said those acts showed ``inappropriate parenting

skills.''

But Martin allowed prosecutors to use other allegations of abuse.

They may say Schwarz forced the boy to wear a T-shirt printed with a

humiliating obscenity - another of her abuse convictions - and that

she choked him and deprived him of food until he collected cans for

her.

Assistant State Attorney Scott Cupp said some of the disallowed allegations,

such as keeping the boy home from school, are crucial to show ``ill

will, hatred and evil intent, part of jury instructions in second-degree

murder cases.''

The boy's father also was home at the time of the death, and prosecutors

want to show ``who was calling the shots, who was the disciplinarian,

who was the one who really ran the home and was responsible for taking

care of the child,'' Cupp said.

The state plans to call about 25 witnesses, including three experts

and a teacher who previously testified that she spoke almost exclusively

with Jessica Schwarz, not the boy's father.

Schwarz's attorney, Rendell Brown, said many of the points were not

relevant.

“We're really saying that we have no knowledge of this murder,''

he said.

The trial is expected to last at least seven days.

Back To Top