Home --> AJ's Story --> AJ's Story: Newspaper Articles --> 1993 Page 4

A.J.'s Story

- Newspaper Articles

The following links take you to various articles in AJ's story as it

appeared in the South Florida media.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE INFORMATION ON THIS SITE BEFORE ASKING.

Thank you!

|

|

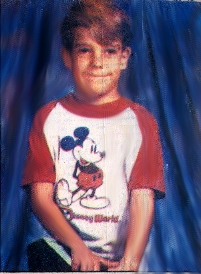

In Loving Memory Of Andrew James "A.J." Schwarz April 24,1983 - May 2,1993 "Beautiful Child who has found love from the angels...RIP..." |

|

This

page contains articles from the Palm Beach Post and The Sun-Sentinel

from the year 1993. |

|

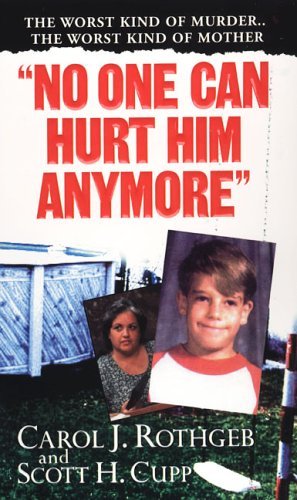

If you are interested in reading the FULL DETAILS of this case aside from what is posted here, please purchase "No One Can Hurt Him Anymore" by Carol J.Rothgeb and Scott H. Cupp. Mr. Cupp thinks it's the book that nobody will read...please show your support and show him that you care about AJ, too by ordering his book by clicking on the cover image below.

Jury

Blasts HRS, Indicts Caseworker -- Warnings of Boy's Abuse Ignored (12/15/93)

Jury Lists Proposals For HRS -- Child Protection Role is

Criticized (12/16/93)

Charge Pinpoints HRS' Problems -- Heavy Caseload Linked

to Indictment (12/16/93)

'Oddball' Grand Jury Decision (12/16/93)

Keep History of Abuse Allegations to Help Avert Tragedies

in Future (12/19/93)

HRS Investigator's Job Pressure-Filled (12/19/93)

No Excuses -- An Editorial (12/19/93)

Grand Jury: HRS Urged Quantity Over Quality (12/20/93)

Woman Can't Visit Children During Holiday (12/24/93)

Schwarz Won't See Daughters (12/24/93)

JURY BLASTS HRS,

INDICTS CASEWORKER

WARNINGS OF BOY'S ABUSE IGNORED

The Palm Beach Post

December 15, 1993

JENNY STALETOVICH

A grand jury Tuesday indicted a state health worker who investigated

the abuse of a 10-year-old boy later found dead, saying she threatened

to take a neighbor's children if the woman continued meddling in the

case.

The grand jury then turned its wrath on the state Department of Health

and Rehabilitative Services.

In a scathing report, the grand jury recounted a series of mistakes

on the case and depicted HRS as an agency whose workers are more worried

about closing cases than protecting children. ``It is the grand jury's

desire that this report not be ignored but be carefully considered to

determine necessary changes,'' the report reads.

Barbara Black, 43, an HRS investigator assigned to the Andrew ``A.J.''

Schwarz case, was arrested late Tuesday and charged with extortion by

threat, a second-degree felony punishable by up to 15 years in prison.

Black, who could not be reached for comment, has worked for the agency

since 1990.

A.J., a wiry little boy whose struggles with HRS became legendary with

neighbors, was found dead in May. Before his death, HRS recorded one

warning sign after another. Among them are Black's abuse investigation

reports.

Black was called to investigate when a neighbor complained that A.J.'s

stepmother, Jessica Schwarz, beat him with her keys and smoked crack

cocaine. Schwarz has been charged with second-degree murder in A.J.'s

death.

The complaint was unfounded, Black wrote in her reports. When A.J.'s

half sister said Schwarz gave her a bloody nose, workers removed the

girl but Black never followed up with an investigation of A.J., reports

show.

Neighbor Eileen Callahan, who lives across the street from A.J.'s house,

called HRS in January after he appeared with a broken nose and black

eyes, sources said. But it apparently wasn't a call she made easily.

Frightened by the family, whose fights frequently attracted deputies,

Callahan worried about getting involved, Assistant State Attorney Scott

Cupp said. Callahan called one neighbor, then another, hoping to persuade

them to make reports, too.

When Black visited the house again, A.J. and his stepmother said he

fell off his bicycle. Black couldn't find evidence of abuse in the home.

Then she paid a visit to Callahan, Cupp said.

``She threatened Callahan, saying that she was going to charge her with

an abuse complaint if she continued to call in,'' Cupp said. ``She calls

her up and lays an HRS special on her.''

Black threatened to take Callahan's children. Callahan quickly called

her neighbors and told them to back off, Cupp said.

In the report issued with Black's indictment, the grand jury claims

that had HRS done its job properly and followed all the warning signs

that appear again and again in hundreds of documents, the agency might

have saved A.J.

The report, based on testimony from caseworkers and investigators, neighbors

and documents, shows a system riddled with basic inadequacies: disregard

of crucial recommendations, poor record-keeping that virtually served

as no record, and lack of communication between officials with various

agencies assigned to the case. Another major problem - a problem which

Black was praised for in job evaluations - was paying attention more

to quantity than quality. In an evaluation completed a month after Black

investigated A.J.'s black eyes, a supervisor wrote: ``Seldom has a backlog

and requires minimal supervision. . . . Seldom has a caseload totalling

10.''

After A.J.'s death, a supervisor congratulated Black for helping her

unit reach the applaudable goal of having the lowest backlog in the

state. In 1991, a supervisor wrote:

``Ms. Black is considered the backbone of unit 14 and has been the key

to backlog reduction. Not only has she mastered her caseload by efficiently

maintaining an active caseload of less than 10 cases, but she has closed

cases for fellow investigators and a vacated position.''

District Administrator Suzanne Turner agreed with some of the grand

jury's findings, but objected to others, especially one citing ``genuine

fear of (HRS') power to remove children from anyone involved (e.g. reporters

of an incident).''

``The `genuine fear' of the department concerns me and I have not heard

that before,'' Turner said. ``I don't think there was any intention

on anybody's part to leave a child in a risky situation and I don't

think anybody involved thought anybody would do anything to him.''

Meeting some of the recommendations, like reviewing cases more carefully,

has already started, she said. Other recommendations, like keeping a

record of unfounded cases, would require special legislation. In 1990,

three weeks after A.J. came under HRS protection, a jury convicted an

HRS caseworker of felony child abuse in the death of 2-year-old Bradley

McGee. An appeals court later overturned the conviction. Black, who

was released late Tuesday on her own recognizance without bond, is being

used as a scapegoat, her attorney, Nelson Bailey, said. ``The whole

country is on a paranoid binge of prosecuting adults having anything

to do with children,'' he said. ``It's a finger pointing and it comes

after every child's death.''

WARNING SIGNS

Andrew J. Schwarz's files had enough information in them to strongly

suggest removing him from the home. There appeared to be an overwhelming

drive by the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services to keep

Schwarz with his natural father even when the Child Protection Team,

staff meetings and other information showed this was not in his best

interest.

Back To Top

JURY LISTS PROPOSALS FOR HRS

CHILD PROTECTION ROLE IS CRITICIZED

Sun-Sentinel

December 16, 1993

By MIKE FOLKS Staff Writer

A grand jury report that criticized the role state child protection

officials played in the life and death of Andrew "A.J."Schwarz

was a symbolic indictment of the system itself, officials say.

The report, issued Tuesday by the Palm Beach County grand jury that

investigated A.J.'s May 2 death, contained several recommendations for

improving the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services'

role in protecting children.

The recommendations, directed at HRS and the State Legislature, included

having HRS investigators leave criminal aspects of investigations to

police trained in handling child abuse cases. The grand jury also recommended

providing more money to be used to reduce HRS workers' caseloads.

"I think the report suggests, and quite frankly states, that the

system in its present state is failing children," said Palm Beach

County Assistant State Attorney Scott Cupp, who heads the Crimes Against

Children prosecution unit.

Regarding the grand jury's recommendation that HRS should leave child

abuse investigations to police, HRS Secretary James Towey on Wednesday

said: "We should not be kiddie cops. HRS can do social work. We

are not police. ... I think we've been a dumping ground for jobs no

one else has wanted to do."

HRS districts are working with local police agencies to develop written

guidelines for when police should take over an investigation, Towey

said.

It is not always easy to tell the point where an HRS investigation ends

and a criminal investigation begins, said Linda Radigan, assistant HRS

secretary for Children and Families.

Many reports are complaints of inappropriate supervision, head lice

and other items that would not need police involvement, Radigan said.

Alison Hitchcock, who supervises a unit of protective investigators,

said HRS tries to involve everyone who needs to be. "We try to

use a team approach as much as we possibly can," she said.

Tuesday's grand jury report contained the following recommendations:

-- HRS supervisors should be more responsible in adhering to HRS policies,

and more emphasis should be placed on the quality of work, not speed

or the quantity of cases closed.

-- HRS needs to establish a central filing system on each child that

is investigated. The system would include reports of abuse, neglect,

foster care, counseling and medical documents, which would be made available

to HRS departments, the courts, police, guardians ad litem and prosecutors.

-- HRS should create a central file of reports of unfounded abuse complaints

to see if repeated unfounded complaints reveal possible patterns of

abuse.

-- HRS needs additional money to hire more trained personnel in the

areas of Child Protective Services, Child Protective Investigations

and Quality Assurance.

HRS spokeswoman Nancy Lambrecht said that inadequate financing causes

many of the problems cited by the grand jury. "We've been saying

that for years," she said.

Lambrecht said she hopes the grand jury report may educate the public

and the Legislature about the need for more revenue to hire additional

trained personnel to handle the agency's growing caseload.

Back To Top

CHARGE PINPOINTS HRS' PROBLEMS

HEAVY CASELOAD LINKED TO INDICTMENT

Sun-Sentinel

December 16, 1993

By LARRY BARSZEWSKI Staff Writer

Barbara Black has worked 14 years for the state, including almost four

years investigating child abuse and neglect complaints, and makes $23,600

a year.

She has received glowing evaluations from her supervisors, both for

the quality of her work and the quantity of the cases she has handled

and closed.

Now a Palm Beach County grand jury says she may have gone too far to

keep at least one abuse case closed. And to a larger extent, she typifies

what the grand jury concluded this week is a failure of the HRS system:

overworked and undertrained staff members earning negligible salaries.

Local HRS workers had empathy for Black on Wednesday, wondering if one

of their cases would blow up in their faces.

"Everybody knows that it could be them, either in this particular

situation or if there happens to be another situation," said Alison

Hitchcock, a supervisor of investigators in the district's Riviera Beach

office. "People work for HRS because they want to help families,

not because of the pay, not because of the long hours and not to have

the community point a finger at them in a situation like this."

But the grand jury said Black, 43, went over the line. It indicted her

on a charge of extortion by threat, a second-degree felony, saying she

threatened to take away the children of a woman in January who called

in an abuse complaint against a neighbor, Jessica Schwarz.

Jessica Schwarz's stepson, Andrew A.J. Schwarz, 10, drowned in his family's

backyard pool at its home west of Lantana in May. The grand jury indicted

the stepmother on a second-degree murder charge in October and came

back with the charge against Black on Tuesday.

The grand jury found a pattern, saying A.J.'s files had enough information

to warrant removing him from the home. His death may have been prevented

if procedures had been followed and evidence acted upon, the grand jury

report said.

"Right now, the country is on a paranoid binge of prosecuting adults

who have anything to do with children. They go overboard to lay blame,"

said Nelson Bailey, Black's attorney.

Assistant HRS Secretary Linda Radigan said threatening to take away

the children of an abuse reporter is not appropriate. However, she said

the public must realize that investigators are often inundated with

false complaints.

"We do try hard to discourage people who we think are harassing

another family from filing a report," Radigan said. "Investigating

a family is a very intrusive, painful process. It is important for us

to protect families from that process if we think someone is making

a call that is a harassment call."

The grand jury's criticisms of the HRS system make it clear the agency

needs more money to hire more trained personnel in child protection

areas.

"We can only help so much given the resources we have," said

Hitchcock, who was an abuse investigator for four years.

HRS Secretary James Towey did not find much out of line with the grand

jury's report and used it to sound a call to the state Legislature to

give more money to his agency - saying it has a $4.7 billion budget

and a $10 billion need.

"My heart is sick about the death of that boy in May," Towey

said. "We don't even know how much abuse is going on. This is what

happens when a state invests so poorly in its children."

The grand jury said the lack of money and staff leads the agency to

emphasize quality over quantity. In Black's case, she was lauded in

1991 for her ability to get through cases and was recognized for the

"lowest backlog in the state."

Her evaluations consistently complimented her ability to accurately

assess the need for emergency interventions and her workload rarely

exceeded 10 cases. However, she did not act to remove A.J. from his

home.

"We're not going to be hurrying up people to reach false conclusions,"

Towey said. "I don't want to see any more deaths. ... We've got

to do better."

Back To Top

'ODDBALL' GRAND JURY DECISION

The Palm Beach Post

December 16, 1993

JENNY STALETOVICH

Anger over the state's cavalier reaction to dismissal of criminal charges

in the death of a 10-year-old boy may have caused a grand jury to reverse

its decision, sources said Wednesday.

An indictment charging a child-welfare worker with threatening a neighbor

who called in abuse allegations stunned state officials, the worker's

attorney and prosecutors, the sources said.

Because grand jury proceedings are secret, the reason for the jurors'

change of heart may never be known. But sources suspect that the Department

of Health and Rehabilitative Services' bravado last month after learning

no criminal charges would be filed shocked jurors struggling with the

death of Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz.

After the November decision, district administrator Suzanne Turner said

her workers did a ``respectable'' job and had followed policy.

The attorney representing the worker says that really gnawed at jurors.

``It was enough to make them want to indict,'' attorney Nelson Bailey

said. ``It's a very oddball decision by the grand jury which apparently

surprised the state prosecutor and everybody else.''

One thing is certain: Grand jurors found fault after fault with HRS.

And although HRS officials are reluctant to admit specific errors, Secretary

Jim Towey said his agency desperately needs help.

In the indictment, jurors charged HRS protective investigator Barbara

Black with extortion by threat, a second-degree felony carrying a maximum

15-year jail sentence. The jury, which indicted A.J.'s stepmother on

second-degree murder charges in October, also issued a report detailing

errors by the agency.

In the wake of the indictment, the agency has rallied around Black,

43.

On Wednesday, she was told to stay home because she ``needed a day of

rest,'' but she stopped by the office when news of her indictment turned

a staff meeting with the agency's assistant secretary, Linda Radigan,

into a confidence-building session, program administrator Sandy Owen

said.

``Yesterday (Radigan) was coming to say how good it was everything was

over but found out on the plane that things had changed drastically

and came to offer support,'' Owen said.

Black, who became a protective investigator in 1990, will be reassigned

pending the outcome of her trial.

While the indictment came as a surprise, prosecutors and police have

known from the day A.J. was found dead that Black allegedly threatened

a neighbor who called in abuse charges.

In a lengthy police report released to The Palm Beach Post Wednesday,

neighbors detailed their frustration with the state agency.

Early on May 2, after A.J.'s father found his naked body mottled with

bruises, detectives arrived to investigate. Within an hour, neighbors

had circled the house at 5881 Triphammer Road, grumbling about the strange

events that occurred there and their attempts to call HRS.

In all, 15 would testify before the grand jury, and about 25 would make

statements to prosecutors.

A detective overheard neighbors' complaints and reported them to his

sergeant, who ordered statements taken. Eileen Callahan, who lived across

the street, was the first interviewed.

Callahan, who said she had seen A.J.'s stepmother violently curse him,

told the detective she called HRS after A.J. broke his nose in January.

Two days later, Detective Chris Calloway, who had investigated the January

complaint, returned to take a taped statement. Callahan, 27, said after

the HRS investigator and Calloway dismissed the charge, the HRS investigator

called her the next day and told her to leave the family alone. If she

continued to ``make up'' charges, Black told her, she would be prosecuted,

according to Calloway's report.

Callahan said she called A.J.'s caseworker, Joan Wyllner, to complain.

Wyllner told her to write a letter, Callahan said. When she asked for

the investigator's name, Wyllner said she could not find it, Callahan

said.

Owen, the program administrator, said Wyllner has never mentioned the

call to her. Nor does any record of the complaint appear in Black's

personnel file.

Such confusion among the ranks is one thing Towey hopes to clear up.

HRS has ``promoted fidelity to the system more than to child protection,''

Towey said. ``Here's what happens to workers when something blows up:

They're sad about the tragedy and (then wonder) is my head going to

roll.

``The system doesn't work. I know that,'' he said. ``On the A.J. Schwarz

case, we could have done a better job.''

GRAND JURY FINDINGS

In its review of Andrew 'A.J.' Schwarz's death, a grand jury found mistake

after mistake by the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services

and insisted on a number of changes.

Here is a summary of what jurors found wrong:

ENOUGH evidence existed to remove A.J. from the home, yet HRS seemed

to ignore warnings from counselors and concentrate on keeping him staying

there.

HRS did not follow its own policies.

WORKERS failed to follow up reports or advise other districts, departments

within its own district, police or court-appointed guardians of events.

EXPERT recommendations from the Child Protection Team were not followed.

RECORDS were maintained so sloppily that jurors could not determine

if documents were falsified. Important files were incomplete and changes

were made without notation of who made the changes or when.

NOT enough workers were available.

NO clear chain of command or assignment of responsibilities exist.

WORKERS are pressured to wrap up cases.

The grand jury recommended that the agency:

PLACE more emphasis on the quality of work instead of the quantity,

and work should be closely watched to see it is being done properly.

MAKE sure its workers are sensitive in handling cases, because witnesses

may be wary of making reports.

CREATE a central filing system.

KEEP records of unfounded complaints.

LET police handle criminal investigations rather than workers trained

in social services.

DESIGN a plan for making sure reports are followed up.

HIRE more workers.

PAY more attention to trends and nuances in cases.

Back To Top

KEEP HISTORY OF ABUSE ALLEGATIONS TO HELP AVERT TRAGEDIES IN FUTURE

Sun-Sentinel

December 19, 1993

Andrew "A.J."Schwarz is another young casualty of a social

services system that failed to protect him.

A.J. was the 10-year-old abused boy who was found dead in May, lying

nude in an above-ground pool at the family home west of Lantana. An

autopsy concluded the boy died from drowning.

His stepmother, Jessica Schwarz, was indicted by a grand jury in October

on a charge of second-degree murder, four counts of aggravated child

abuse, witness tampering and one count of felony child abuse. Deputies

say the child was either held under water or hurt so badly that he couldn't

get out of the pool.

What makes this case even more horrible is that the state Department

of Health and Rehabilitative Services had loads of information in its

files to show that the boy was being abused, but ignored the evidence

and insisted on keeping him with his natural father and stepmother.

Last week, a Palm Beach County grand jury indicted the HRS worker who

not only did an abysmal job investigating and following up previous

abuse complaints involving A.J., but allegedly threatened that the agency

would take away a neighbor's children if the woman continued to meddle

in the case.

The HRS child protective investigator, Barbara Black, faces a charge

of extortion by threat, a second-degree felony.

The neighbor had called HRS to report suspected abuse against A.J. by

his stepmother in January. The same day, Black allegedly made the threat

against the woman.

The grand jury also ripped HRS for failing to act on evidence that A.J.

should be removed from the home. It found that the boy's death might

have been avoided if procedures had been followed.

There's no question the grand jury report hit a nerve. HRS officials

say they cannot argue with many of its findings.

Now, the agency must act to carry out the grand jury's recommendations,

which include requiring HRS supervisors to be more responsible in adhering

to policies and placing more emphasis on the quality of work, not the

quantity of cases closed.

But HRS can't bear all the blame. The Florida Legislature also shares

some of the responsibility.

In their stupidity, legislators in 1990 passed a law requiring HRS to

destroy unfounded abuse complaints in 30 days - exactly the opposite

of what they had approved only a few years earlier.

Now, the grand jury is properly recommending that a record of unfounded

abuse cases be kept, since it is the only way HRS workers can be aware

of a history of unconfirmed abuse allegations about a child. In addition

to reinstituting these requirements, the Legislature also must amend

the law to mandate that police, not HRS, be the primary investigators

of child abuse.

HRS and the Legislature must act to help other children like A.J. whose

lives may otherwise be snuffed out because of bureaucratic incompetence.

Back To Top

HRS INVESTIGATOR'S JOB PRESSURE-FILLED

Sun-Sentinel

December 19, 1993

By LARRY BARSZEWSKI Staff Writer

If Victor Perez overreacts, he can destroy a family.

But if he does not act soon enough, it's a child that could be hurt

- or killed.

"We have to make a determination, is that child safe in the home?

We have to make that decision right away," said Perez, who investigates

child abuse and neglect complaints for the Florida Department of Health

and Rehabilitative Services in Palm Beach County.

"Can the children go back in the home? That's the hardest decision

any protective investigator has to make," Perez said.

Investigators for the local HRS district are second-guessing themselves

more these days in the wake of a grand jury indictment last week of

one of their co-workers.

The grand jury charged Barbara Black with extortion by threat, a second-degree

felony, saying she threatened to take away the children of a woman who

called in an abuse complaint. The woman complained in January about

Jessica Schwarz, whose stepson, A.J. Schwarz, drowned in May. Jessica

Schwarz is now charged with second-degree murder.

The investigators empathize with Black, because they face the same heavy

caseloads, the same pressures to finish cases quickly, and the same

long hours for little pay.

Perez, 53, has been working with neglected children since 1965, including

nine years with HRS. He makes about $23,000 a year. He drives a 1985

Dodge Charger with 164,000 miles on it.

"I'm sure I could find a better job than this, but I chose this,"

Perez said. On Friday, Perez had to decide if he should take into custody

a 5-year-old boy who had been slapped at school by his father in front

of his teacher. In starting his investigation, Perez found an unclassified

1992 report about the boy having a rope tied around his neck.

"The first words out of [Victor's) mouth were, `It sounds like

A.J. Schwarz,'" said Alison Hitchcock, Perez's supervisor in the

district's Riviera Beach office, which covers the county north of Forest

Hill Boulevard. The grand jury chastised HRS workers for not picking

up on previous abuse complaints about A.J. and said the boy might still

be alive if he had been removed from his father and stepmother's home.

Perez took the case, but he had plenty of others to keep him busy.

"I'm working on five cases right now, back to back," Perez

said. Actually, he had 13 cases open, but he had to concentrate his

attention where the risk of harm was the greatest:

-- A boy who was allegedly made to eat soap, stand in a corner in his

room for up to three hours and go without dinner, sometimes up to five

days in a row. Perez is seeking court-ordered supervision of the child

because a judge has allowed the father - who instigated the punishments

- to return to the house. There are prior complaints against the family,

including sexual abuse against the boy by the father's brother.

-- A 3-year-old with three burns on his body: a mark across the face

from an iron, a burn on his chest from a lightbulb and a larger scar

on his stomach from a cigarette lighter. Although it does not look as

if the child's parents inflicted the burns, Perez wants to remove the

child and two siblings because of gross neglect.

-- A 2-year-old girl who was beaten by her mother and her mother's boyfriend.

The adults were convicted and put on probation, and a court is likely

to give the mother custody of the girl again. Perez is fighting this

because the girl was severely abused for not being toilet-trained -

and she is still not toilet-trained.

-- A child with four distinctive burns on her back. The girl is living

with a relative and is under HRS supervision. Perez is doing an assessment

about the neglect, possibly to remove the child from the home.

Then there are the other cases, such as the 16-year-old delinquent,

the drug-dependent newborn, the three teen-agers in a home with a history

of being abused.

Officials put pressure on workers to close cases. They send a daily

printout to each office of its backlogged cases. The printout on Friday

showed Hitchcock's section was 26 cases over the desired level. Districtwide,

there were 636 open cases, about 200 more than desirable, Hitchcock

said.

HRS Secretary James Towey told local officials after Black's indictment

not to worry about the number of open cases, to focus on the quality

of the investigations and not the quantity of cases closed, Hitchcock

said.

"How long will it last? Who knows?" said Hitchcock, who feels

the pressure herself and passes it on to her subordinates. The open-case

printout still is sent out every day.

Perez dealt as he could with his other cases on Friday, but his focus

was the complaint that arrived late on Thursday about the school incident,

which had to be investigated in 24 hours.

"Every other case has to be put aside, because I have to determine

the safety of this child," Perez said.

He started the day getting background information, criminal histories

and prior complaints logged with HRS about the family. He interviewed

the boy and his 6-year-old sister at school before confronting the parents.

He had a sheriff's deputy accompany him to the home west of West Palm

Beach after school because he had no idea what might happen.

"Once the father knows that HRS is involved, we never know how

parents are going to react," Perez said. "This one's already

had prior contact with HRS."

The father reacted angrily, but Perez's homework paid off. He knew the

father had an outstanding warrant, so the deputy threatened the father

with arrest if he did not cooperate. The father agreed to go to the

HRS office to be interviewed, where Perez said it would be less confrontational.

After meeting with the father, Perez made several determinations. The

main one is that the children can stay at home. Both parents need to

learn parenting skills, and counseling will be arranged, but the children

are in no immediate danger. The father agreed to voluntary supervision.

The emergency was over, but the case was far from done when Perez left

work on Friday. He must transcribe all his conversations for the day,

once in writing and once on a computer. There are up to three dozen

other forms he must fill out

Two-thirds of the cases that come to the office are unfounded and go

nowhere, but they all require the same amount of paperwork and make

the same demands on investigators' time, supervisor Hitchcock said.

"Sometimes doing the best we can doesn't satisfy anybody,"

Perez said. "In the meantime, the computer kicks out new cases."

Back To Top

NO EXCUSES -- AN EDITORIAL

The Palm Beach Post

December 19, 1993

For more than seven months, officials with the Florida Department of

Health and Rehabilitative Services have made excuses for their agency's

failure to prevent the death last May of a 10-year-old Lantana boy named

A.J. Schwarz.

Our social workers are overworked and underpaid, the officials have

said. The evidence of abuse was insufficient, the officials have said.

The testimony from neighbors and others was inadequate, the officials

have said.

But now we know there was no excuse for A.J.'s death. We know there

was no excuse for HRS to leave A.J. in the home of his stepmother, who

is charged with killing him. Despite his terrible home life, despite

his being tugged between dangerously dysfunctional families, last week's

grand jury report said it all in one grim understatement: ``Andrew J.

Schwarz's files had enough information in them to strongly suggest removing

him from the home.''

A.J. Schwarz was placed in what HRS calls protective supervision in

1990 after abuse charges against his stepfather, with whom he and his

mother were living. How well was he protected?

Here's what the therapists said: ``This is a target child . . . living

in exactly the wrong situation. Parenting is not meeting his needs .

. . should receive therapy for his past sexual abuse. Family is holding

secrets and avoiding confrontation with HRS and the Child Protection

Team . . . History definitely indicates severe and continuing emotional

abuse which certainly should be investigated. - Child Protection Team,

Feb. 23, 1993.

HERE'S WHAT THE GRAND JURY SAID: ``There was an overwhelming drive by

HRS to keep Andrew with his natural father even when the Child Protection

Team showed this was not in his best interest. . . . HRS' policies and

procedures were not followed. There was a lack of diligent follow-up

and communication between counties, groups within the department and

with police investigators. It's difficult to determine if records are

falsified when they are not adequately maintained. . . . White-out,

overwriting, cutting pages and taping pages were observed. - Grand Jury,

Dec. 14, 1993.

The picture that emerges is of bureaucratic mentality gone mad while

a little boy struggles to survive. ``We must not substitute process

for people,'' HRS Secretary Jim Towey says. But that's precisely what

happened.

And yet. The system almost worked - could have worked. Warning signs

blinked in hundreds of documents. In January, neighbor Eileen Callahan

swallowed her fear of the hostile Schwarz family and called HRS when

she saw A.J. with a broken nose and black eyes.

For her courage, she was terrorized. HRS investigator Barbara Black

allegedly threatened to take Ms. Callahan's children if she didn't stop

calling. Last week, Ms. Black was arrested and charged with extortion

by threat. The charge will be difficult to prove. But the grand jury

made its point.

A mind-set that obscures people by elevating time management and ``good''

numbers will lead to disaster when every number is someone's life. Yet

Barbara Black was known - and commended - for her ability to reduce

HRS' backlog by closing cases quickly.

A.J.'s case is not an isolated example. Grand juries in Orlando, Miami

and Jacksonville have also leveled scathing charges at HRS for its handling

of child abuse. Mr. Towey and Suzanne Turner, the HRS administrator

for Palm Beach County, have held their respective jobs since July and

August. They bear no direct responsibility for A.J.'s death. Yet where

are their expressions of moral outrage, their pledges to reverse the

dangerous HRS drift?

The courts will focus on Ms. Black and on Jessica Schwarz, charged with

murdering her stepson. The public will focus on how Gov. Chiles - and

Mr. Towey and Ms. Turner - see their responsibility. Eileen Callahan

saw her responsibility clearly. She worried about getting involved.

That was more than anyone at HRS did.

Gov. Chiles has yet to comment on the Schwarz case. As of last Thursday,

Mr. Towey hadn't even read the file. How many other children are in

danger because too many HRS workers are worrying about efficiency?

``It is my opinion that Andrew is at risk for physical, emotional and

verbal abuse. HRS is to closely monitor this family.

- Therapist, Center for Children in Crisis, Sept. 17, 1991.

``Professionals' recommendations were not implemented.

- Grand Jury, Dec. 14, 1993.

Andrew J. Schwarz died May 2, 1993.

Case closed.

Back To Top

GRAND JURY: HRS URGED QUANTITY OVER QUALITY

The Palm Beach Post

December 20, 1993

JENNY STALETOVICH

In the months after a 10-year-old boy struggling with an explosive family

came under the protective arm of the state, the state health office

buzzed with exuberance. Banners went up. Memos went out.

The elation had nothing to do with Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz or the thousands

of other children in the state's care.

What excited Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services workers

was a simple number. For the first time, District 9 had the fewest backlogged

cases in the state, racing past all the other districts and climbing

to the top of a weekly ranking report issued from headquarters in Tallahassee.

In a letter to the investigator who would later handle A.J.'s care,

acting district director Jim Hart wrote:

``Congratulations on reaching what appeared for so long to be the unreachable

goal for District 9 CYF Protective Investigations: `lowest backlog in

the state.' ''

District officials insist they never meant workers to sacrifice quality

for quantity, but a grand jury decided last week that's exactly what

happened.

Not only did jurors issue a harsh report picking apart HRS problems

point by point, but they indicted Barbara Black, the 43-year-old investigator

Hart so vigorously praised, charging her with threatening a neighbor

who called in abuse complaints about A.J.

Jurors, who earlier indicted A.J.'s stepmother on second degree murder

charges and cleared the agency of criminal wrongdoing, reversed their

decision, possibly out of fear that HRS would ignore their findings.

This week, HRS Secretary Jim Towey acknowledged the crisis crippling

his agency, saying he was grateful for the report.

``HRS as a whole has been more committed to process than the people

in our care,'' he said. ``The complexity of the system is no excuse

for us not doing our jobs well.''

But some say it will take more than a mere nod of recognition.

``Will the system change? The system will change if people really care

enough about what happens to children,'' said Harriet Goldstein, a social

worker for 50 years and director of field placement at Barry University.

``Without strong advocacy, persistence and demands, these are forgotten

families and forgotten kids,'' said Goldstein, who has given expert

testimony to grand juries in other states. ``They're out of the community

sight and nobody pays attention until there's a death. Then there's

momentary alarm before everybody goes back to quiescence.''

In their report, what jurors found particularly troubling was the agency's

emphasis on closing cases and an urgency to keep things looking good

despite trouble brewing beneath the surface.

``There's no question there was pressure all over the state to decrease

the backlog,'' Towey said.

Workers first began feeling the pressure to keep cases down in late

1988 and early 1989 when the state centralized its abuse investigations

by setting up a single hot line in Tallahassee, Hart explained.

``Now you have a centralized number and the administration was very,

very process oriented. They used to track whether you had the lowest

caseload.''

The ranking reports began daily, then dropped to biweekly and finally

slowed to weekly, said John Perry, who works in the Tallahassee hotline

office.

``We've always emphasized quality of work over quantity,'' Hart said.

``But I'll tell you, under the previous administration, there was a

lot of emphasis on numbers and getting things down.''

Towey eliminated the weekly reports when he stepped in as secretary,

although he maintains a computer listing which workers can read.

When HRS put A.J. in protective supervision in November 1990, District

9 ranked eighth in the state. Caseworkers averaged 40 to 50 cases a

month and protective investigators struggled with a rolling average

of 15. At the same time, the death of a 2-year-old Lakeland boy had

prompted legislators to quickly provide money for more than 600 new

workers to try to ease the pressure of mounting caseloads.

But the injection of money and workers would not be enough.

District 9 climbed to No. 2 more than two years later, but the ranking

did little for A.J. On May 2, his body - mottled with yellowing bruises

- was found in his backyard pool. A report was issued several weeks

before his death calling for continued investigation of the case: In

addition to emotional abuse, a counselor believed he may have been covering

up for his stepmother when he said he broke his nose falling off a bicycle.

In the weeks following the report, a meeting was held, but A.J . stayed

with his stepmother.

Although state statute requires investigations to be closed in 45 days,

Hart says the district never enforced the rule.

``There are reasons why you can't close a case. For instance if it's

pending in the courts, you can't close it,'' he said.

While working on A.J.'s case, Black - who was charged with extortion

by threat, a second degree felony carrying a possible 15-year prison

sentence - was a model investigator.

In the early 1980s, HRS hired Black as a data file clerk. After earning

her bachelor's degree in social work from Florida Atlantic University

in 1986, she was promoted to a child support investigator.

The next year, she transferred to the Florida Department of Corrections

to become a probation officer. In 1990, HRS rehired her as a protective

investigator.

In the three years she investigated child abuse, Black received remarkably

good evaluations, exceeding her supervisor's expectations case after

case. Moving quickly on the career ladder, she kept her caseload to

a minimum, rarely going over 10. One supervisor noted she was more than

capable of doing what she wanted most: becoming a supervisor.

Black, born and raised in West Palm Beach, declined to be interviewed

through her attorney, Nelson Bailey.

Bailey suggested that Black may be a scapegoat for the faults of an

entire system and society has misplaced its blame.

``Their performance system was predicated on closing out cases,'' he

said. ``Part of the problem is the public is looking to place the blame

and the blame lies in the public's own lap. They've got the system and

it doesn't work.''

Towey, who has not read A.J.'s files documenting the blunders workers

made, has been careful about commenting on the case partly because A.J.'s

mother is preparing a lawsuit against the agency.

``The breeding ground for child abuse is much more complex than HRS

can handle. I'm sick of hearing about the system. We've all got to be

held accountable,'' Towey said.

Towey and District Administrator Suzanne Turner have come up with some

solutions, although they have not completed a review of the May death.

Among the changes are: asking police to take the lead in abuse investigations

rather than relying on investigators trained in social work; opening

some reports for public scrutiny so taxpayers can see what HRS is doing;

breaking the district into areas and assigning supervisors based on

geographical boundaries rather than a straight chain of command.

Even with the changes, Towey says HRS alone cannot solve the problems

children face.

``I'm not going to lie to you and say if HRS would just do its job,

then all our problems would go away,'' he said. ``I want this to be

a moment where the community comes forward and says, `How do we stop

child abuse?' ''

Back To Top

WOMAN CAN'T VISIT CHILDREN DURING HOLIDAY

Sun-Sentinel

December 24, 1993

A woman accused in the May death of her stepson, Andrew "A.J."Schwarz,

10, may not visit with her children over the Christmas holiday, a judge

ruled on Thursday.

Palm Beach County Circuit Court Judge Walter N. Colbath Jr. denied Jessica

Schwarz's request to see her two daughters.

However, Colbath, deferred ruling on whether Schwarz will be able to

visit with her daughters after the holiday. The judge said he would

make that ruling after the daughters have given depositions in connection

with A.J.'s death.

Jessica Schwarz, 38, was indicted on Oct. 8 for second-degree murder,

four counts of aggravated child abuse, witness tampering and one count

of felony child abuse. She remains free on bail pending trial.

A.J. was found by his father, David Schwarz, about 6 a.m. on May 2 lying

nude in an above-ground pool at the family home west of Lantana. Deputies

have said Jessica Schwarz either held A.J. under the water or hurt him

so badly that he could not get out of the pool.

Back To Top

SCHWARZ WON'T SEE DAUGHTERS

The Palm Beach Post

December 24, 1993

Author: JENNY STALETOVICH

Estimated printed pages: 2

A woman accused of killing her 10-year-old stepson after months of abuse

won't spend Christmas with her two young daughters after a psychologist

said she enlisted the girls in a ``conspiracy of abuse.''

In a hearing Thursday, Dr. George Rahaim said he saw Jessica Schwarz

wave to the girls and, minutes later, make a crude gesture to a state

prosecutor. Rahaim said he's not sure the girls saw the gesture but

he said it was an example of the silent manipulation she practices.

``It's very subtle,'' Rahaim said. ``These are girls riding to school

in the rain while their brother had to walk. . . . I liken it to a trusty

in a concentration camp, where you have to live with unspeakable things

happening to other people.''

Except for passing glimpses in court appearances, Schwarz, 39, has not

seen the girls, 5 and 11, since a grand jury indicted her in the death

of Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz in October.

Saying the girls had become depressed living with their grandparents

in Palm Bay, Schwarz's attorney, Rendell Brown, tried to persuade Judge

Walter Colbath to allow weekend visits. In a two-page letter to Colbath,

the older girl wrote:

``My little sister only knows how to wright (sic) her name so I am writing

for both of us. Please, Please let us have a Merry Xmas.''

Colbath, who was ``very concerned about the subtle abuse,'' agreed to

let Schwarz send letters and give presents to the girls, but not see

them.

Afterward, Brown said Schwarz probably would not write.

Colbath initially prohibited contact between Schwarz and the girls when

he released her from jail on $150,000 bond and confined her to her home.

He based his decision in part on a videotape recorded by investigators

hours after A.J.'s body was found May 2, in which prosecutors said Schwarz

bullied the girls.

``You got a big mouth,'' Schwarz told her younger daughter. ``You don't

talk to nobody no more. You just say, `I don't know.' ''

The girl had told detectives Schwarz hit A.J. and dumped green dye in

his hair the day before his death, reports show. Schwarz's treatment

of her stepson alarmed neighbors as early as May 1992, when a complaint

was filed with an abuse hot line. The Department of Health and Rehabilitative

Services, which had been monitoring the case since 1990, conducted investigations,

but said no evidence was found.

Then, two months before his death, Rahaim and therapists warned that

Schwarz was, at the least, emotionally abusing A.J.

Earlier this month, the grand jury charged HRS investigator Barbara

Black with extortion, saying she threatened to take a neighbor's children

who had complained about the former truck driver.

In the video, Rahaim said the youngest girl ``was extremely anxious

and frightened for her mother and felt a sense of responsibility. .

. . The kid was trying to get her story straight.''

Walking into court Thursday, Schwarz waved at the girls. Minutes later,

before the hearing began, she made the crude gesture to Assistant State

Attorney Joe Marx, Rahaim said. Outside the courtroom, her girls momentarily

forgot the adults sparring inside when a Santa Claus passed by. Even

with the door closed, their squeals of delight could be heard as he

shouted, ``Ho, ho, ho. Merry Christmas.''

Back To Top