Home --> AJ's Story --> AJ's Story: Newspaper Articles --> 1993 Page 3

A.J.'s Story

- Newspaper Articles

The following links take you to various articles in AJ's story as it

appeared in the South Florida media.

PLEASE DO NOT COPY THE INFORMATION ON THIS SITE BEFORE ASKING.

Thank you!

|

|

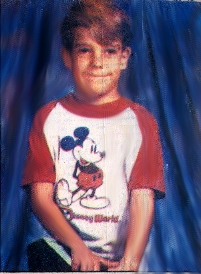

In Loving Memory Of Andrew James "A.J." Schwarz April 24,1983 - May 2,1993 "Beautiful Child who has found love from the angels...RIP..." |

|

This

page contains articles from the Palm Beach Post and The Sun-Sentinel

from the year 1993. |

|

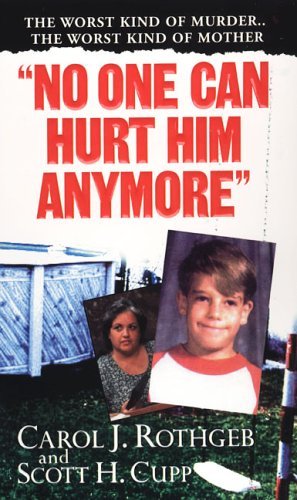

If you are interested in reading the FULL DETAILS of this case aside from what is posted here, please purchase "No One Can Hurt Him Anymore" by Carol J.Rothgeb and Scott H. Cupp. Mr. Cupp thinks it's the book that nobody will read...please show your support and show him that you care about AJ, too by ordering his book by clicking on the cover image below.

HRS

To Go Before Grand Jury in Boy's Death (11/3/93)

Jury Issues No Indictments Against HRS (11/13/93)

HRS Cleared of Criminal Wrongdoing in Boy's Death (11/13/93)

AJ Had No Chance For Life: Files Show Physical and Emotional

Abuses (11/14/93)

A Sorrowful Life: How The System Failed AJ (11/28/93)

HRS Not Wholly To Blame, Agency Chief Says (11/28/93)

Woman Charged in Stepson's Death Wants to See Girls (12/3/93)

Do An Autopsy of HRS to Protect the Next AJ (12/5/93)

Worker Indicted, HRS Hit in Abuse Case (12/15/93)

HRS Worker Indicted -- Agency Criticized in Child Abuse

Case (12/15/93)

HRS WORKERS TO

GO BEFORE GRAND JURY IN BOY'S DEATH

The Palm Beach Post

November 3, 1993

JENNY STALETOVICH

Prosecutors will go back before a grand jury on the case of a 10-year-old

boy whose stepmother has been indicted in his death - this time to question

social-service workers responsible for protecting him, sources said.

State Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services workers will

testify for a day and a half on Monday and Tuesday, sources said.

Some workers have been asked to voluntarily testify, while others have

been ordered by subpoena to appear, an HRS official said. Workers who

testify under subpoena receive at least partial immunity from prosecution.

Following the Oct. 8 indictment of Jessica Schwarz in the death of Andrew

``A.J.'' Schwarz, investigators said they had not closed the case and

hinted that other arrests may follow.

But HRS District Administrator Suzanne Turner denied any wrongdoing

by the agency and said that workers are cooperating with the investigation.

``I would certainly hope it's not implied that HRS or any of our employees

are guilty of any criminal action or negligence because it's my understanding

that just basic information . . . is being sought,'' she said.

Although the number of workers who will testify is not clear, one name

has surfaced. Barbara Black, an investigator who looked into a tip that

Schwarz broke A.J.'s nose five months before his May 2 death, received

a letter to appear, sources said.

Black, who could not be reached for comment, was hired as a protective

investigator in May 1990 and early on earned praise for closing cases

quickly.

Black was assigned to A.J.'s case when a Broward County judge gave Schwarz

and A.J.'s father, David Schwarz, temporary custody in December 1990

after A.J.'s stepfather sexually molested his half sister, records show.

A.J. told a therapist he wanted to live with his father and, like his

father, grow up to be a truck driver.

But trouble erupted in the house at 5881 Triphammer Road in early 1992

when A.J.'s half sister said Jessica Schwarz gave her a bloody nose.

A.J.'s half sister returned to Broward County, but A.J. remained with

the Schwarzes under HRS supervision.

Then, on Jan. 24, a caller phoned HRS, claiming Schwarz broke A.J.'s

nose. Black and a deputy visited the house. With a swollen nose and

bruised eyes, A.J. told Black and the deputy he fell off a bicycle.

Schwarz, her daughter and A.J.'s half sister repeated the story. After

talking to A.J.'s protective-services counselor, who doubted Schwarz

hit her son, Black and the deputy decided the charge was unfounded,

reports show.

But three days later, A.J.'s therapist - questioning him during a scheduled

session - said she was not satisfied with the explanation.

The next week, Jessica Schwarz and A.J. reported to the Center for Children

in Crisis where a counselor questioned them again. The counselor concluded

there was ``rather severe and continuing emotional abuse'' and recommended

HRS investigate more thoroughly.

More than a month passed before HRS workers met with therapists and

school officials to discuss the case. At the close of a tense meeting

with Jessica Schwarz, who cursed violently, everyone agreed to work

more closely, records show.

A little over a month later, A.J. was found dead.

Black first worked for HRS from 1979 to 1987, before becoming a probation

officer for the Department of Corrections. When she returned to HRS

as an investigator, she earned praise for jumping in where a worker

abruptly left and quickly clearing up 40 cases, records show. In one

evaluation, she was called ``the key to backlog reduction.''

Back To Top

JURY ISSUES NO INDICTMENTS AGAINST HRS

Sun-Sentinel

November 13, 1993

Author: By MIKE FOLKS Staff Writer

A Palm Beach County grand jury investigating the role the Florida Department

of Health and Rehabilitative Services employees played in the life and

death of Andrew "A.J."Schwarz issued no indictments on Friday,

but the investigation is not over.

The grand jury will reconvene in December to continue the investigation,

said Mike Edmondson, spokesman for Palm Beach County State Attorney

Barry Krischer.

Edmondson's comments came late Friday after the grand jury ended a weeklong

session during which HRS employees were called to testify in A.J.'s

case.

A.J., 10, was found by his father about 6 a.m. on May 5 lying nude in

an above-ground pool at the family home west of Lantana.

An autopsy showed A.J. died from drowning, but his stepmother, Jessica

Schwarz, 38, was indicted on Oct. 8 for second-degree murder and four

counts of agggravated child abuse. Jessica Schwarz also was indicted

on a charge of witness tampering and one count of felony child abuse

for trying to influence the testimony of another child about the circumstances

of A.J.'s death.

HRS files in A.J.'s case show that workers had concerns about A.J. and

possible abuse a year before his death. Neighbors had reported suspected

child abuse by Jessica Schwarz against A.J. to HRS, but the boy remained

in the custody of his father, David Schwarz, and stepmother.

According to grand jury indictments, Jessica Schwarz forced A.J. to

eat from a bowl placed next to the family cat's litter box and punished

him by making him stay home from school. The indictments also accuse

Jessica Schwarz of forcing her stepson to wear a shirt that read, "I'm

a worthless piece of ----, don't talk to me" and making him edge

the yard with a pair of hand scissors.

At his death, A.J., a third-grader at Indian Pines Elementary School,

had more than two dozens cuts, bruises and scrapes on his body.

Investigators said they suspect Jessica Schwarz either drowned A.J.

or injured him so severely that he could not swim and drowned.

Back To Top

HRS WORKERS CLEARED OF CRIMINAL WRONGDOING IN BOY'S DEATH

The Palm Beach Post

November 13, 1993

JENNY STALETOVICH

A grand jury cleared state health workers Friday of any criminal wrongdoing

in the death of a 10-year-old boy whose stepmother was indicted for

murder by the same jury a month ago.

The ruling came as a relief to State Department of Health and Rehabilitative

Services officials but infuriated the boy's mother.

``The workers responsible for him are guilty of murder,'' said Ilene

Schwarz, whose son, Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz, was found dead in his stepmother's

pool on May 2. ``As long as HRS can get away with this, it's going to

continue because HRS doesn't get punished when they do wrong.''

HRS workers took A.J. from Schwarz's home in May 1990 after he reportedly

watched his stepfather sexually molest his half sister. They placed

him with Jessica Schwarz and his father seven months later.

During the 28 months he lived with his stepmother and father at 5881

Triphammer Road, workers visited him only 13 times despite a policy

calling for monthly visits, records show.

More than a month before he died, a therapist warned that A.J. suffered

emotional abuse and warned HRS workers to investigate.

Assistant State Attorney Scott Cupp, who also presented the case against

Jessica Schwarz to the grand jury, has declined to comment about the

HRS presentation.

``There's been reviews periodically to determine if we felt there was

anything done out of line,'' said district administrator Suzanne Turner.

``We feel with the knowledge they had at the time, that they did a respectable

job.''

Turner declined to answer specific questions until she consults with

the district's attorney, but said workers continually struggle with

heavy caseloads.

``Somebody can't sit back and say, `You should have done it this way'

because they weren't out there at the time,'' Turner said. ``How much

can you investigate when you've got a caseload of 40 or 50? You just

can't get in to all those homes.''

Back To Top

A.J. HAD NO CHANCE FOR LIFE

FILES SHOW PHYSICAL AND EMOTIONAL ABUSES

Sun-Sentinel

November 14, 1993

By LARRY BARSZEWSKI

Staff Writer

The suspicious drowning of Andrew "A.J." Schwarz in May ended

a 10-year-old life that never stood much chance of happiness - or normalcy.

Recently released case files from the state Department of Health and

Rehabilitative Services in Broward and Palm Beach counties document

years of physical and emotional abuse.

They tell the story of a boy from a broken home who was so afraid of

being abandoned that he refused to say anything bad about the parent

he happened to be living with - no matter how bad life was at home.

"A calendar on the wall showed several lengthy groundings [A.J.)

was placed on for punishment," said a report filed after his death.

"It looks as if [A.J.) spent most of his life grounded."

Eight months before A.J. died, the guardian ad litem who represented

him in court concluded: "Andrew Schwarz is a depressed, anxious

child with severe and long-standing parent problems. Last spring, he

became suicidal, withdrawn and was unable to assess reality; he may

have been close to a psychiatric breakdown. If Andrew cannot live in

our world, he will withdraw into his own."

The guardian ad litem did not know how little time A.J. had left.

About 6 a.m. on May 2, A.J.'s father found the boy's naked body floating

in the family's backyard pool.

Detectives immediately suspected foul play. Water in the above-ground

pool was shallow enough to allow A.J. to stand up and breathe. His body

had more than two dozen cuts, bruises and scrapes that probably occurred

over several months.

A Palm Beach County grand jury indicted his stepmother last month on

charges of second-degree murder and child abuse. The abuse included

making A.J. cut grass with scissors, sit outside naked, eat dinner next

to the cat's litter box, and wear a shirt saying, "I am a worthless

piece of s---; don't talk to me."

The grand jury continued its investigation last week, looking at the

role HRS may have played in A.J.'s death. It will look at the matter

again when it meets in December, said Mike Edmondson, spokesman for

the Palm Beach County State Attorney's Office.

HRS officials are reluctant to talk about how the agency handled A.J's

case because of the investigation, which might lead to charges against

HRS workers.

"What was done or not done with A.J., it's not appropriate to comment

on now," said Karen Miller, HRS legal counsel in the Palm Beach

County district.

Which leaves the question: Should HRS have acted, given what officials

knew and suspected about possible abuse in A.J.'s home?

A.J. was born on April 24, 1983, to David and Ilene Schwarz of Fort

Lauderdale. The couple divorced in 1985 and A.J.'s mother received custody

of him and her 5-year-old daughter from a previous relationship. The

HRS files are filled with allegations about life during A.J.'s early

years: His mother was on drugs during her pregnancy with him; she hit

him in the head with a frying pan when he was 3; her boyfriends beat

him. Ilene Schwarz said HRS workers believed what her husband's new

wife Jessica told them - and that Jessica had the children lie about

their mother. "The [HRS) workers that we had, everything that Jessica

told them they kept as gospel," A.J.'s mother said on Friday. "They

took everything at her word without checking into it."

A.J. almost drowned when he was 3, chasing a ball into a swimming pool,

but he was not taken to a hospital after being under water for two to

five minutes. His mother remarried in 1989 to Thomas Luke, who beat

her and was sentenced to jail for sexually molesting A.J.'s half-sister

- at least once in front of A.J. His stepfather also punished A.J.,

making the boy take off his pants and then hitting him with a belt,

A.J. told caseworkers.

HRS stepped into the picture in May 1990, when A.J.'s half-sister, then

10 - revealed the sexual abuse by Luke.

HRS deemed Ilene Schwarz an unfit mother for failing to protect the

children. The agency placed the children with her sister, who soon begged

out of the agreement.

Her family suggested several maternal relatives as foster parents, but

officials said they all had criminal pasts. An ex-brother-in-law with

a clean record finally came forward, but he was candid with officials.

"He stated if the natural father is drug free, he then should be

given the opportunity to raise the children," one report read.

"[He) stated [not) under any conditions should the children be

reunited with their mother, since she is unfit and never provided them

a decent living environment." The children first went to foster

care after living with their aunt. The foster mother reported they arrived

with lice and wearing outgrown and dirty clothes. They were placed with

A.J.'s father and stepmother, David and Jessica Schwarz, in November

1990.

The couple met on the road as truckers and were married in 1989. David

"Bear" Schwarz continued to spend a lot of time on the road,

leaving child-rearing to Jessica, who was a day-care worker at the time.

Besides A.J. and his half-sister, then 7 and 11, the family included

Jessica Schwarz's 8-year-old daughter from a previous marriage and the

couple's own daughter, who was 2. A.J. and his older half-sister were

in regular counseling sessions.

In September 1991, Broward County Circuit Judge Arthur Birken decided

to keep the two children with A.J.'s father and stepmother. The reports

received before his decision conflicted.

The children "are reported to be thriving in their current placement,

where David and Jessica Schwarz are providing a loving, nurturing and

stable home," an HRS worker wrote.

But "loving" and "nurturing" were not words often

associated with life at the Schwarz house in Concept Homes west of Lantana.

"I cannot recommend this placement without reservations,"

wrote a counselor from the Center for Children in Crisis. "I have

serious concerns because of allegations made by [A.J.'s half-sister)

concerning physical abuse by Mr. Schwarz. ... [She) also disclosed what

appeared to be excessive and inappropriate punishment."

The September court decision came after A.J. told a psychiatrist: "My

family treats me like ... I'm a little Dumbo."

The decision came shortly after David Schwarz had his wife arrested

on domestic assault charges, the Sheriff's Office reported.

The children told HRS they wanted to stay at the house "because

they like it there, and they want to stay with their dad, whom they

love."The half-sister recanted her charges about abuse - she "expressed

great fear about repercussions after the disclosure," a counselor

wrote. It infuriates A.J.'s mother that HRS did not do more.

"Everyone in their right mind knows that when a child is terrified,

they're not going to come forward," she said on Friday.

Family life rapidly deteriorated after Birken's ruling.

A.J.'s second-grade teacher at Indian Pines Elementary School described

the boy as a very bright child who was very loving and needed love in

return. The teacher would send good behavior notes home with A.J., but

his stepmother responded with notes saying what a bad boy he was.

"He was forbidden by his stepmother to receive any snacks or goodies

in school, attend any school parties or go on any field trips,"

A.J.'s guardian ad litem reported. "Mrs. Schwarz explained to [the

teacher) that these prohibitions were necessary to balance the long

list of bad things he had done at home."

Near Christmas 1991, stepmother Jessica Schwarz left a screaming message

on an HRS counselor's home answering machine, saying she wanted the

two children out of the house, although David Schwarz called back and

said it was a misunderstanding.

In January 1992, A.J. was hospitalized for six weeks at the Psychiatric

Institute of Vero Beach. The family said A.J. had been riding his bike

into traffic, jumping off ladders and trying to drown his younger half-sister.

While A.J. was at the hospital, his older half-sister was removed from

the home after David and Jessica Schwarz complained they could no longer

handle her. The girl at first did not want to go back to her mother

and was placed in foster care, but the mother and child were reunited

a half-year later. Just weeks after leaving David and Jessica Schwarz's

home, the half-sister told her mother "her stepmother had slapped

her and given her a bloody nose," the mother told HRS workers.

A.J., by this time, was an 8-year-old functioning more like a 5-year-old,

evaluators found. He sucked his thumb, hid his face and suffered from

"post-traumatic stress disorder," his psychiatric evaluation

said.

A.J. was released from the hospital in March.

In May 1992, a neighbor said Jessica Schwarz hit A.J. with a key chain.

HRS found no marks on him, but reports cautioned: "There is something

very suspicious about this incident. ... Whoever receives this case,

keep your eyes and ears open. ..."

"Andrew felt very safe at school. ... I just think he went home

to a horrible, horrible life," one of his teachers said last week.

"I have real qualms about HRS. I just really think they could have

come a lot more than they did. There were some real red lights."

More abuse reports surfaced, including at least eight that HRS wrote

off as "unfounded." HRS should bring reports of abuse to the

police's attention before tossing them aside, said Lt. Steve Newell

of the Palm Beach County Sheriff's Office homicide division.

"The bottom line, HRS shouldn't be doing these investigations,"

Newell said on Friday. "Law enforcement should be doing the criminal

investigations."

HRS investigated a broken nose and black eye A.J. received in January

1993. The family said his shoelace got caught in a pedal while he was

riding a bicycle and he fell.

Although officials were suspicious, a medical consultant found the story

consistent with the injuries - and a Sheriff's Office investigation

found nothing. But Newell said deputies were working at a disadvantage.

"We were not given all of the other cases," he said.

A psychosocial evaluation in February recommended that HRS consider

placing A.J. in a foster home to ensure he was not being emotionally

abused. About the same time, Ilene Schwarz - A.J.'s mother - began stepping

up efforts to get A.J. back. The mother complained frequently to HRS,

alleging abuse at her ex-husband's home. The pressure was getting to

stepmother Jessica Schwarz.

"Jessica states this whole mess with A.J.'s custody being in question

again has really created a chaos for her," caseworkers reported

in April. A month later, A.J. was dead. Ilene Schwarz, A.J.'s mom, said

HRS must bear the blame for what happened.

"My son's dead because he was under their care, under their supervision,"

she said. "They'd better come back with some indictments for the

HRS workers. I'll be damned if I'll let them get away with a slap on

the wrist."

Back To Top

A SORROWFUL LIFE: HOW THE SYSTEM FAILED A.J.

The Palm Beach Post

November 28, 1993

JENNY STALETOVICH

To the boy who thought of himself as the ``little dumbo,'' the world

was a scary place.

He saw alligators, fire, ghosts, lions and dead dragons covered with

blood on a psychological exam.

``He was also preoccupied with angels,'' a therapist wrote.

State health workers said his parents were bad. Doctors poked him, made

him look at black spots and gave him medicine to make him happy.

The state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services took Andrew

``A.J.'' Schwarz from his mother in May 1990 after abuse charges surfaced

against his new stepfather. They searched for a relative to take him,

finally settling on his father and stepmother - a couple they previously

considered too bitter about A.J.'s real mom to take over his care.

After he was found dead in the family pool and his stepmother was charged

with his murder, The Palm Beach Post went to court to get A.J.'s HRS

records. In hundreds of pages of documents the sad, scary, out-of-control

life of a 10-year-old boy spills onto the pages, portraying a boy who

once called himself ``little dumbo'' and said he felt closest to the

family dog.

The Post is able to chronicle A.J.'s life in such detail only because

he is dead. The death allowed a judge to open the A.J. files where HRS

workers, assigned to take care of the boy, carefully documented all

the sadness, all the signs, all the mistakes. Even their own.

And still, A.J. died a horrible, mysterious death.

So the question remains: Can an arm of government responsible for thousands

of children be strong enough to wrap itself around one child and protect

him?

``To scapegoat HRS might make you feel good, but that's very simplistic,''

HRS secretary Jim Towey said. ``We'll take our share of the blame, but

it starts with the adult committing the heinous act.''

A grand jury Oct. 8 charged Jessica Schwarz, 38, with second-degree

murder and child abuse. The same grand jury ruled earlier this month

no HRS workers acted criminally but continues to review the case. As

they read the hundreds of pages, they'll come across an eerie call from

his mother two days before her child's death:

Both she and her mother have been having very bad nightmares, a caseworker

wrote April 30. She fears she will never see him alive again and something

bad is going to happen.

HIS HOME LIFE

A.J. adored his father. His mother, Ilene Schwarz, 39, made him so nervous

he once threw up in the judge's chambers before a court hearing she

attended. But his dad, whom he called the Bear, was a burly truck driver

A.J. worshipped. Trouble is, Bear, 37, was never home.

The real caretaker in Bear Schwarz's home was his second wife, Jessica.

A truck driver as well, she was a tough-love kind of person who again

and again chastised A.J. in front of others. A.J. never cried. He never

acted up in school. But once, when his parents admitted him to a hospital

in Indian River County, doctors found his psychological state so critical,

they ordered nurses to check him every 15 minutes. Even young kids commit

suicide.

He stayed in that hospital room for six weeks. The father he adored

and the stepmother who ran the house visited him twice.

After A.J. was found floating in his backyard pool May 2, his body bruised

and beaten, deputies were shocked at what they saw at the house. It

was nice enough. The girls' room - where A.J.'s half-sister and stepsister

stayed - was what you'd expect. Neatly decorated, scattered with the

litter of small children who play games.

But A.J.'s room, a garage converted to a bedroom, was disturbingly different.

It was bare. No Nintendo, no stereo, no TV, none of the things the girls

had. Pictures of the girls were hung throughout the home. But not a

single picture of A.J. adorned the walls, even though his school photo

shows an adorable, smiling portrait of a small boy.

A small boy tormented by life.

ANDREW `A.J.' SCHWARZ

To understand A.J. is to understand he was different things to different

people.

His mother remembers him as a little antsy, but not out of control.

Therapists saw a depressed boy with behavioral problems who desperately

needed treatment. His teacher thought he had trouble concentrating,

but said he was never a disciplinary problem.

To his stepmother, he was a bad, bad boy.

A.J. ``knows what he is doing and uses rule infractions as a way to

get attention . . . he is a `bad boy' with a grin on his face,'' she

told his court-appointed guardian in September 1992. Just after his

death, Jessica Schwarz said: "He likes to start fights with people

and (sit) back and watch it . . . We're dealing with this child who

was never right. He was never normal . . . He never followed any rules

because he figured they came from an adult and adults hurt him.''

Her attorney, Rendell Brown, advised both Jessica and Bear Schwarz not

to be interviewed for this story.

``There's no way they can gain anything by any conversations in the

press because of the furor in the community,'' he said.

A.J.'s last teacher remembers the first time she met A.J. at an open

house. Standing next to his stepmother, he dropped his head and looked

at the floor as she belittled him.

``She said, `You have to be firm with him. He is a liar. He will try

to fool you, but if you're a smart teacher, you'll be able to catch

him. You're not to give him any books because if he brings them home,

he loses them and I'm not paying for them,' '' Jessica Schwarz told

the teacher. The next day the teacher called him to her desk and gave

A.J. the kind of reassurance life had denied him.

``I said, `Andrew, I know you're a wonderful little boy and whatever

school supplies you need, you tell me.'

``He was a very, very sweet little boy.''

The teacher, who did not want her name used in this story because she's

afraid of Jessica, took great pains to write the notes she sent home

with A.J.

``She would pounce on (criticism) and delight in it,'' the teacher said

about A.J.'s stepmother. ``I knew he was sensitive. I would get notes

from her and he would watch me read them. I remember one time him looking

at me and saying, `It's a bad one, isn't it?' ''

Even so, the teacher never saw him cry or complain.

``I found him to be over and above it, kind of like, `You're not going

to get me down. You're not going to break me.' ''

Whether it was because he simply felt safe away from home, or thrived

on the attention, A.J. always liked school. But Jessica Schwarz would

keep him home for days. When the teacher told his court-appointed guardian,

the guardian assured her things were under control in the home. She

also talked to her principal, guidance counselor, even A.J.

``When I would talk to (A.J.) about home problems,'' the teacher said,

``he would look at me and I would look at him and I would say, `Are

you sure?' and he would say, `Yup.' And he knew and I knew that was

not normal.''

SEARCHING FOR A HOME

The spring of 1990 was A.J.'s first real HRS experience. It was a mess,

and so was A.J.

On the initial medical exam, doctors found he was hyperactive. He couldn't

hear well, suffered from asthma, which easily developed into bronchial

pneumonia, and his front teeth were rotten. In school pictures, A.J.

smiled with his lips pressed shut.

After he and his half-sister were taken from his mom's home, HRS tried

to follow the agency policy of keeping the kids with family.

A.J.'s mom had 10 brothers and sisters. A big, boisterous family of

Navy brats, most of them had settled in South Florida. But eventually

it came down to this: not one was up to HRS standards.

The children stayed briefly with an aunt while workers searched for

a more permanent solution. But when her marriage collapsed and she made

plans to move, HRS said the children couldn't go with her.

Besides that, the aunt had gotten more than she bargained for. Ilene

Schwarz left the state after she voluntarily turned over her kids, thinking

the move would solve her problems. But HRS said she had to do certain

things - attend therapy, find a house, get a job.

Meanwhile, A.J. and his half-sister turned out to be a handful. And

Ilene's sister wasn't getting any support from the family.

A.J. would eventually remain in protective custody until his death,

36 months later and 27 months longer than policy manuals recommend.

A supervisor should have reviewed the case, but there's no record that

ever happened.

While workers in Broward County wrestled over where to put the kids,

Palm Beach County workers investigated a complaint about A.J.'s stepmother.

On May 29, 1990, Ilene Schwarz turned over the children to HRS in Broward

after her second husband molested A.J.'s half-sister.

Two days later in Palm Beach County, an anonymous caller said A.J.'s

stepmother had tried to sell her daughter for $35,000. When an HRS investigator

and deputy arrived at the house, Jessica Schwarz said she thought about

giving the baby up for adoption because she and A.J.'s father were having

problems, but said she would never hurt her. After watching her treat

a rash on the girl and feed her, they dismissed the charges. HRS never

mentioned the report in later evaluations of the couple.

Exasperated with Schwarz and her family, caseworker Winifred O'Reilly

focused on putting the kids with A.J.'s father and stepmother. Dismissing

the earlier evaluation that determined Bear and Jessica weren't the

right caretakers, O'Reilly made a phone call to Bear Schwarz, then used

information from the earlier report compiled by a Palm Beach County

caseworker. She wrote a new recommendation for the judge, pushing the

couple as A.J. and his half-sister's new guardians.

The relationship between all (was) positive, she wrote.

LIVING WITH THE BEAR

When David Schwarz, ``the Bear,'' walked into court to persuade a judge

to give him the children, the judge, the guardian ad litem, the HRS

attorney and even the court bailiff said he did not appear to be a fit

father.

The judge gave him liberal visitation so he could bond with the children,

and ordered the children placed in foster care.

They arrived with heads full of lice, their foster mother later wrote.

Just getting them cleaned up was a chore.

Within days, HRS embraced Bear and Jessica and began taking steps to

move the kids in with the couple, married since 1990. Jessica Schwarz,

who had spent weekends with them, sent a 10-page letter blasting Ilene

Schwarz and detailing her own love for children:

Please, for the kids' sakes, give them both to us and I promise we will

comply with everything you want us to do. Give (the children) a break

and (Bear) and myself a chance to prove we can make a difference and

change their lives for the best.

As talks with the couple intensified, Ilene Schwarz's simmering anger

exploded. She called workers and the court-appointed guardian, screaming

and making threats. Fort Lauderdale police had to be called when she

showed up at the foster mother's house demanding to see the children.

She cursed angrily on the guardian's answering machine.

The guardian got a restraining order and visitation between the children

and Ilene stopped.

A month after the October 1990 hearing, a judge said the children should

live with Bear and Jessica Schwarz but remain under protective supervision.

The judge ordered all to undergo psychological evaluations and insisted

the children continue therapy.

The family got off to a rocky start. Early on, workers saw flashes of

Jessica Schwarz's temper. She called the caseworker one week after the

kids moved in, angry that the promised food stamps and Medicaid had

not arrived. Wants everything now, the caseworker wrote. Four days later,

the caseworker spoke to Bear Schwarz:

Jessica too hyper and starts trouble by calling everyone before process

could be started, she said Bear told her. Stated she (Jessica) is on

pain medication . . . May be reason for her mood swings.

Meanwhile, Ilene Schwarz began court-ordered parenting classes and had

a drug evaluation which found no drug abuse.

Just two months after they moved in, A.J.'s half-sister made her first

complaint that Jessica Schwarz hit her. An HRS investigator visited

the house Feb. 14, 1991, with deputies, decided the complaint was unfounded

and gave Jessica Schwarz the name of a crisis counselor. Five days later,

the girl told her therapist that Jessica Schwarz hit A.J. The therapist

decided the girl was being manipulative.

Within a week, an anonymous complaint was made to HRS. A night caseworker

went to the house with a deputy and talked to A.J.'s father, who suspected

his ex-wife had made the call. Seeing no sign of abuse, the worker dismissed

the case without further investigation.

Four months after he moved in with Bear and Jessica, five months after

a judge ordered it, A.J. got his psychological evaluation. He desperately

needed intensive therapy.

THE MELTDOWN

Six weeks later and five months after the children moved in, HRS caseworker

Jannie Sutherland stopped by the suburban Lantana house for the first

time. HRS caseworker manuals require monthly home visits.

Sutherland said she found everything in order.

What she missed was the inner turmoil in the house at 5881 Trip-hammer

Road. Bear Schwarz, out of the house driving cross-country, had undergone

a psychological evaluation, which found he needed treatment and drank

too much. The therapist said he should stop drinking and be given periodic

urine tests to monitor him.

He also told the therapist he thought his son acted ``stupid.''

. . . has feelings of resentment and hostility especially toward people

who make demands on him, the therapist wrote.

Jessica Schwarz never underwent a psychological evaluation as ordered.

And the neighborhood, alive with kids and nosy neighbors, was a breeding

ground for arguments between families. Jessica Schwarz declared war

on them, calling deputies repeatedly over the next 15 months. Several

anonymous abuse complaints are thought to have come from neighbors.

If Sutherland knew about the deputies' visits, she made no note in her

files. Three weeks after she visited the house, deputies had to break

up a fight between Bear Schwarz and his drunken wife, who had shoved

a neighbor and smashed a car window.

Concerns surfaced in therapy.

I have serious concerns because of allegations made by (A.J.'s half-sister)

concerning physical abuse by Mr. Schwarz, a therapist from the Center

for Children in Crisis wrote in September 1991. Although (the girl)

recanted allegations of being physically abused by Mr. Schwarz, it must

be noted that (she) has expressed great fear about repercussions after

disclosure. Later a therapist wrote that A.J.'s half-sister was doing

fine but ``it is the adults around her who need help.''

Still, workers aimed at permanently placing the children with Bear and

Jessica Schwarz.

On New Year's Day 1992, the woman who promised to do ``what's best''

for the kids was arrested for driving drunk with a blood alcohol level

2 1/2 times what is legal. The next day, she called HRS in a rage, insisting

HRS take the kids back. Bear called back in minutes trying to reassure

the caseworker.

A.J.'s Broward County caseworker was already worried. Things were ``breaking

down'' in the family, she wrote.

The two HRS districts drew up conflicting case plans. Broward County

wanted to reunite A.J. with his mother. Palm Beach County hoped to establish

permanent custody with his father.

Confusion over the case reached Sutherland's supervisor. She was worried

that Bear and Jessica were turning A.J. against his mother, something

HRS forbids.

Let's discuss last home visit with A.J. Child sounds like a robot and

does not recognize grandmother's voice. Jessica and (Bear) cannot undermine

relationship with mother. Father on road constantly. Is this the court's

intention?

A week later, the two districts settled the matter and decided A.J.

and his half-sister should remain with Bear and Jessica.

The supervisor, Lane Sutton, was fired four months later for falsifying

documents. Her personnel file does not explain what documents she changed.

Just before they fired her, supervisors criticized her unit, saying

two allegations of mismanagement had been filed.

Over the next few months, the family suffered a major meltdown. HRS

removed A.J.'s half-sister after she said Jessica Schwarz gave her a

bloody nose. Jessica later admitted hitting her. That same month, Bear

and Jessica Schwarz checked A.J. into a psychiatric hospital. A.J.'s

stepmother told a doctor the little boy tried to drown Jessica and Bear's

young daughter.

A.J. appears to be suffering from the loss regarding not only his mother,

but also his sister, a doctor wrote during his stay. He will need to

mourn and grieve in supportive therapy.

During his six-week stay, A.J.'s father and stepmother visited him twice.

When he got home, A.J. became adamant about staying with his father,

even though Bear Schwarz was never home. He told his caseworker he never

wanted to see his mother again.

HRS workers continued documenting Jessica Schwarz's erratic and often

hostile behavior.

Still, they pushed to have A.J. stay with his father and stepmother,

who at this point was working at a day-care center.

The first abuse complaint concerning A.J. came in May 1992, when an

anonymous caller said Jessica Schwarz beat him with her car keys, smoked

crack, loaned her car to someone and was so stoned she couldn't remember

who had it. She later found the car at a crack house in Boynton Beach,

police reports said.

HRS investigators found merit to the abuse complaint and referred the

family to the Child Protection Team. A.J. remained in the home, in his

stark garage bedroom.

Jessica Schwarz tried to explain her rough parenting to A.J.'s court-appointed

guardian, calling it ``tough love.'' But the guardian wondered if she

should change, considering A.J.'s poor self-esteem and ongoing battle

with depression. He suggested she attend counseling. Within a week,

a newly assigned Broward County caseworker, Ramona Settles, reported:

Jessica has been very uncooperative with HRS and says she never wants

A.J. to reunite with his mother.

As Settles became more involved in the case, she increased pressure

to have A.J. see his mother and half-sister. But A.J.'s new Palm Beach

County caseworker, Joan Wyllner, thought they should end HRS supervision

because of a May order that appeared to give permanent custody to Bear

and Jessica Schwarz. Over the next few months, HRS began sorting through

the bureaucratic mess.

A.J.'s half-sister, in foster care and going to therapy with her mother,

was making progress and began overnight visits with Ilene. A.J.'s situation,

however, was getting worse.

A.J'S LAST DAYS

The last six months of his life seemed to careen forward, out of HRS's

control and certainly out of A.J.'s control.

In January, A.J.'s nose was broken and his eyes blackened. An anonymous

caller to HRS said his stepmother beat him. But when an abuse investigator

and deputy visited the house, A.J. said he fell off his bicycle. They

left without deciding whether abuse had occurred.

When he shied away from answering a therapist's questions about the

accident two days later, the therapist became alarmed.

The next week, Jessica Schwarz canceled two appointments. She didn't

want to submit to a crisis therapist's questions. When she did, she

complained A.J. masturbated in front of her and she was afraid to hug

him.

The family is keeping secrets from HRS, the counselor wrote.

A.J.'s guardian twice made calls to HRS saying he was concerned.

But the worst was yet to come.

Around the little neighborhood of cinder block homes, parents winced

at the bizarre punishments Jessica Schwarz inflicted on her stepson.

Neighbor Shirley Leiter found A.J. out before dawn one morning, collecting

cans for the community service his stepmother received after driving

drunk.

Another neighbor's daughter said Jessica Schwarz made him eat from a

bowl by the cat's litter box one night.

One day, he arrived at the girl's house to play wearing a Tshirt Jessica

Schwarz had scribbled on in marker, warning people not to talk to him,

saying he was worthless.

A.J.'s stepmother started sending odd notes to school with him, his

teacher said. Schwarz refused to attend therapy with A.J., who was off

his anti-depressant medication because Medicaid refused to pay the bills.

The boy had grown alarmingly thin.

Jessica Schwarz was fired from her job at the day care center in March.

Her boss, fearful of Jessica's temper, called the Sheriff's Office to

have a deputy stand by as she delivered the news.

Three days later, an HRS staff meeting was quickly arranged. It got

off to a shaky start when Jessica Schwarz cursed everyone there.

``When I walked into that meeting, just she and her husband were in

the (room),'' said A.J.'s teacher. ``The first thing she said to her

husband is, `Well, here is the maggot.' ''

During the meeting, the teacher said A.J. had missed 19 out of 44 days.

But by the end, an air of comradery took over, tempers subsided and

everyone agreed to work together.

Ilene Schwarz, still anxious to get her son back, had wanted a hearing.

The Broward workers handling her case backed her and told Palm Beach

County caseworkers the boy should live closer to his mother.

Palm Beach County workers insisted A.J. was fine. He was back in therapy

and back on medication. On April 26, his 10th birthday, A.J.'s guardian

visited his house with presents. Everything looked fine, he said.

Then on May 1, A.J.'s father and stepmother took his half-sister and

stepsister to SunFest in downtown West Palm Beach, leaving A.J. home

alone. A neighbor remembers seeing him peer over a backyard fence. The

last anyone saw of him was at 1 a.m., when another neighbor told police

he saw the boy walking the family dog, the dog he loved so much. Hours

later, his father tossed a sheet over his lifeless body before calling

police.

Autopsy reports showed head injuries so severe that had A.J. not drowned,

he would have surely died from the blows. Jessica Schwarz, who was later

videotaped coaching A.J.'s stepsister and half-sister - telling them

not to cooperate with detectives - has denied beating him. If beatings

did in fact happen at his house, A.J. never let on, even to the end.

The boy who said he desperately wanted to live with his father and drive

trucks like his father, stuck to his story.

``I often wonder, `Couldn't I have done more? Couldn't I have helped?'

'' his teacher said. ``I will never forget it. I will always wonder.''

CASE CHRONOLOGY

April 24, 1983: Andrew 'A.J.' Schwarz is born at Broward General Hospital,

11 months after his mother and father, Ilene and David ``Bear'' Schwarz,

were married.

August 26, 1985: A.J.'s parents divorce.

May 1989: A year after his mother marries Tom Luke, 37, A.J.'s half-sister

says Luke sexually molested her. HRS puts the kids in protective custody.

June 1990: HRS rejects Bear and Jessica Schwarz as guardians, saying

they are too bitter about A.J.'s mother.

Oct. 10, 1990: Frustrated with Ilene Schwarz, a caseworker begins working

to place the children with Bear and Jessica Schwarz.

Nov. 19, 1990: A judge signs an order putting the children with Bear

and Jessica Schwarz under protective custody.

February 1990: A.J.'s half-sister tells her therapist that Jessica Schwarz

hit her. A caseworker concludes the charges are unfounded.

April 21, 1991: A psychologist finds Bear Schwarz has trouble expressing

anger and has a drinking problem.

Feb. 6, 1992: A.J. is hospitalized at Indian River Memorial Hospital.

Six weeks later a doctor releases him and says he should continue therapy

and take anti-depressant medication for six months.

Feb. 21, 1992: A.J.'s half-sister says Jessica Schwarz beat her. HRS

puts her in foster care.

May 19, 1992: An anonymous caller tells HRS Jessica Schwarz beat A.J.

HRS investigates but concludes the charge is unfounded.

Jan. 24, 1993: HRS receives an anonymous complaint that A.J.'s stepmother

broke his nose. A worker and deputy question Jessica Schwarz, who says

he fell off a bicycle. Three days later, A.J. shies away from telling

his therapist about the injury. The therapist calls HRS.

March 29, 1993: HRS holds a meeting with Jessica and Bear Schwarz. The

meeting starts with Jessica cursing at everyone. By the end, they all

agree to work together.

March 31, 1993: A child-protection therapist finds A.J. is being emotionally

abused and warns HRS not to close the case without investigating further.

May 2, 1993: Bear Schwarz finds A.J., naked and bruised, in the family's

backyard pool.

Back To Top

HRS NOT WHOLLY TO BLAME, AGENCY CHIEF SAYS

The Palm Beach Post

November 28, 1993

JENNY STALETOVICH

The state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services was an agency

already in the angst of self-evaluation by the time A.J. Schwarz came

under its care in May 1990.

Three weeks earlier, a jury convicted a caseworker of felony child abuse

and failing to report suspected child abuse. The caseworker had recommended

a 2-year-old Lakeland boy be returned to his mother and stepfather,

dismissing warnings from his foster parents that the couple abused young

Bradley McGee. Two months later, McGee died after his stepfather angrily

plunged his head into a toilet as punishment for soiling his diapers.

The caseworker's conviction has since been overturned, but the unprecedented

decision - to convict a state worker in the handling of a case - stunned

the agency.

HRS, which historically worked to keep families together, now found

itself pulling them apart.

``HRS is constantly walking a tightrope between families who say, `Don't

you come near my family whether you have a report or not,' and `How

can you pull children out?' '' said HRS Secretary Jim Towey.

Following the conviction, HRS took a pit-bull stance toward child abuse

and began taking children out of homes quicker than workers could be

trained to handle them. In 1989, the Legislature passed the Bradley

McGee Act, which paid for 628 new child welfare workers. Another 93

positions were added during the regular session, increasing the agency

by 26 percent in one year.

Abuse complaints rose 12 percent, from 106,947 in 1989 to 119,324 in

1990. The number of children in foster care quickly rose from 20,308

before McGee's death to 28,334 the following year, according to agency

statistics.

But putting all the blame on the agency is unfair, Towey said.

``When I read over and over, `This could have been prevented,' well,

HRS will take its share of blame, but neighbors could have helped, churches

and synagogues could have helped, and schools.''

Towey hopes to introduce new legislation allowing the agency to reveal

records showing what work HRS has done to help the public understand

the complexity of child-protection cases. In each case, whether HRS

takes children or not, the agency puts the child first, he said.

“I'm sick of this muzzle stuck on my mouth,'' Towey said. ``What

somehow gets lost in the shuffle is: `HRS didn't kill these kids.' ''

Back To Top

WOMAN CHARGED IN STEPSON'S DEATH WANTS TO SEE GIRLS

The Palm Beach Post

December 3, 1993

A woman charged with killing her 10-year-old stepson who was videotaped

telling her tearful daughter not to cooperate with police should be

allowed to see the girl, her attorney said in a motion filed Thursday.

A judge forbade Jessica Schwarz, 38, from contacting her two daughters

in October after viewing the tape at a bond hearing.

In the short tape recorded at the Palm Beach County Sheriff's Office

in May hours after Andrew ``A.J.'' Schwarz's body was found - Schwarz

questioned her daughters, ages 5 and 11, about what they told detectives.

``You got a big mouth,'' Schwarz told the 5-year-old. ``You don't talk

to nobody anymore. You just say, `I don't know.' ''

Days later, the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services

took the girls from Schwarz and placed the girls with her grandparents

in Palm Bay.

Schwarz, state prosecutor Scott Cupp argued, might influence the girls

if allowed to see them.

Palm Beach County Judge Walter Colbath also ordered Schwarz not to leave

her home unless attending court proceedings or meeting with her attorney.

Back To Top

DO AN AUTOPSY OF HRS TO PROTECT THE NEXT A.J.

The Palm Beach Post

December 5, 1993

To the Florida Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services, the

death of 10-year-old A.J. Schwarz in May was what a crash is to commercial

aviation - the worst thing possible. So like airline investigators,

HRS officials have to sort through the wreckage and find out whether

the Lantana boy, who was under HRS' protective supervision for 36 months,

died because HRS failed to act or because there was no way to protect

him.

Calling A.J.'s family dysfunctional is a pathetic joke. According to

HRS rec-ords, he was removed from his mother, Ilene Schwarz, in May

1990 after charges that her husband had abused A.J.'s half-sister. He

so feared his mother that he threw up in a judge's chambers before a

court hearing she attended. He was placed with his stepmother, Jessica

Schwarz, whom neighbors say tormented him. His bruised, naked body was

found floating in his backyard pool May 2. His stepmother has been charged

with his murder. His father, David Schwarz, didn't attend his funeral.

On A.J.'s side was the HRS system the Legislature has created, one in

which the starting salary for protective services workers is $16,000.

One in which those workers supervise an average of 44 families. One

in which the turnover rate among those workers is 68 percent. One in

which workers from Palm Beach and Broward counties juggled A.J.'s case

because family members lived in both places.

Those can be excuses or facts, depending on how HRS wishes to look at

them. ``We'll take our share of the blame,'' HRS Secretary Jim Towey

has said. ``But it starts with the adult committing the heinous act.''

Of course. HRS can't guarantee the agency will prevent every death any

more than the Federal Aviation Authority can prevent every plane crash.

It's also true, as Suzanne Turner, HRS administrator in Palm Beach County,

says, that the agency is dealing with an ``explosion'' of vulnerable

children because of the sick families Florida is producing. ``Rarely

are we called into a case today with just one problem,'' Ms. Turner

says. ``There usually are several - perhaps a mother who's an alcoholic,

a father who abuses the children, too little food, kids fighting and

getting involved in juvenile crime.''

But the reality is that HRS must do more with what it has, even as officials

fight for needed money. Ms. Turner says she'll try to improve HRS in

several ways. She wants the Legislature to let local Health and Human

Services Boards, which oversee local budgets of HRS, move money to where

it's most needed. She wants better information about complaints to the

state's toll-free abuse hotline. She wants to treat families rather

than individuals where possible. She wants to hire aides to help workers

with paper work, freeing them to spend more time with families. She

wants to ask universities to help with training. She wants to improve

communication between HRS and other agencies, including police and schools.

The grand jury report on the case, due later this month, could add to

that list. Like the black box that helps explain a plane crash, it may

provide more clues. We're a long way from justice for A.J. Schwarz.

Back To Top

WORKER INDICTED, HRS HIT IN ABUSE CASE

Sun-Sentinel

December 15, 1993

Author: By MIKE FOLKS Staff Writer

A state child abuse investigator was indicted on Tuesday on charges

of threatening a woman for reporting suspected abuse of a 10-year-old

boy who died in May.

The boy's stepmother is accused of causing his death.

Barbara Black, a child protective investigator for the state Department

of Health and Rehabilitative Services, faces a charge of extortion by

threat, a second-degree felony. The Palm Beach County grand jury also

issued a report critical of the agency's handling of the boy's case.

Among other things, the grand jury found the agency failed to act on

evidence that the boy, Andrew "A.J."Schwarz, should be removed

from his father's and stepmother's home. A.J. was found by his father,

David Schwarz, about 6 a.m. on May 5 lying nude in an above-ground pool

at the family home west of Lantana.

An autopsy showed A.J. died from drowning.

His stepmother, Jessica Schwarz, 38, was indicted by a grand jury on

Oct. 8 for second-degree murder, four counts of aggravated child abuse,

witness tampering and one count of felony child abuse.

At the time of indictment, deputies said Jessica Schwarz either held

A.J. under water or hurt him so badly that he couldn't get out of the

pool. Ilene Schwarz, A.J.'s biological mother, says she is sorry she

listened to HRS workers instead of her heart.

"I should just have gone up there and taken him, whether they charged

me with kidnapping or whatever," said Schwarz, of Fort Lauderdale.

"Because they ignored the complaints and did nothing, my son is

dead."

A.J. and his half-sister lived with Ilene Scharz in Broward County until

1990, when they were placed in David Schwarz's custody. HRS said Ilene

Schwarz failed to protect the children from being molested by her then-husband.

Though she later regained custody of the girl, A.J. remained with his

father and stepmother.

Schwarz said she did all she could within the system to try to remove

her son from the home west of Lantana. But HRS brushed all the complaints

aside, she said.

"Barbara Black (the abuse investigator) was supposed to have investigated

the calls, but she just kept brushing them off," Schwarz said.

She said she "felt furious and helpless" when she saw a report

signed by Black stating that reports of abuse of A.J. were unfounded

and instigated by Ilene Schwarz.

"I want everybody responsible to pay for what they've done,"

Schwarz said. "I don't want my son to have died in vain. I'd like

to prevent another child having to die because of the system."

Assistant State Attorney Scott Cupp said Black is accused of threatening

Eileen Callahan, a neighbor of the Schwarzes, with having her children

taken away from her for filing a false child abuse report.

Callahan had called HRS to report suspected abuse against A.J. by his

stepmother on Jan. 26, and the alleged threat by Black was made that

day, Cupp said.

Black was booked into the Palm Beach County Jail on Tuesday night and

released on her promise to appear in court. She could not be reached

for comment. HRS spokeswoman Nancy Lambrecht said she was unable to

comment on Black's indictment.

Lambrecht did say, however, that HRS officials cannot argue with many

of the findings the grand jury cited in its report.

In its report criticizing HRS' handling of A.J's case, the grand jury

said A.J.'s death may have been avoided if procedures had been followed

and evidence acted on.

"Andrew J. Schwarz's files had enough information in them to strongly

suggest removing him from the home. There appeared to be an overwhelming

drive by [HRS) to keep Andrew J. Schwarz with his natural father, even

when the Child Protection Team, staff meetings and other documented

information showed this was not in his best interest," the grand

jury report said.

The grand jury also cited a lack of follow-up and communication between

HRS workers and police in Broward and Palm Beach counties.

Other problems the grand jury cited on Tuesday in A.J.'s case included:

-- HRS worker caseloads require unreasonable time restraints;

-- Recommendations made by HRS' Child Protection Team were not implemented;

-- Management of records was inadequate.

The grand jury also issued recommendations to HRS and to the state Legislature.

Among them:

-- HRS supervisors should be more responsible in adhering to policies;

-- More emphasis should be placed on the quality of work, not the speed

or the quantity of cases closed;

-- HRS should not conduct criminal investigations, leaving that to police

trained to handle child abuse crimes.

Back To Top

HRS WORKER INDICTED

AGENCY CRITICIZED IN CHILD ABUSE CASE

Sun-Sentinel

December 15, 1993

By MIKE FOLKS Staff Writer

A child abuse investigator was indicted on Tuesday on charges of threatening

a woman for reporting suspected abuse of a 10-year-old boy whose stepmother

is accused in his death.

In addition to the indictment against the state Department of Health

and Rehabilitative Services worker, a Palm Beach County grand jury issued

a report critical of the agency's handling of the boy's case.

Among other faults, the grand jury found the agency failed to act on

evidence that Andrew "A.J."Schwarz should be removed from

his father's and stepmother's home.

The grand jury indicted Barbara Black, an HRS child protective investigator,

on a charge of extortion by threat, a second-degree felony, against

a neighbor who was trying to report abuse against A.J.

A.J. was found by his father, David Schwarz, about 6 a.m. on May 5 lying

nude in an above-ground pool at the family home west of Lantana.

An autopsy showed A.J. died from drowning.

His stepmother, Jessica Schwarz, 38, was indicted on Oct. 8 for second-degree

murder, four counts of aggravated child abuse, witness tampering and

one count of felony child abuse.

At the time of the Oct. 8 indictment, deputies said Jessica Schwarz

either held A.J. under water or hurt him so badly that he couldn't get

out of the pool.

Assistant State Attorney Scott Cupp said Black is accused of threatening

Eileen Callahan, a neighbor of the Schwarzes, with having her children

taken away from her for filing a false child abuse report.

Callahan had called HRS to report suspected abuse against A.J. by his

stepmother on Jan. 26, and the alleged threat by Black was made that

day, Cupp said.

Black was booked into the Palm Beach County Jail on Tuesday night and

released on her promise to appear in court. She could not be reached

for comment. HRS spokeswoman Nancy Lambrecht said she was unable to

comment on Black's indictment. But Ilene Schwarz, A.J.'s biological

mother, says she is sorry she listened to HRS workers instead of her

heart.

"I should just have gone up there and taken him, whether they charged

me with kidnapping or whatever," said Schwarz, of Fort Lauderdale.

"Because they ignored the complaints and did nothing, my son is

dead."

A.J. and his half-sister lived with Ilene Schwarz in Broward County

until 1990, when they were placed in David Schwarz's custody. HRS said

Ilene Schwarz failed to protect the children from being molested by

her then-husband. Though she later regained custody of the girl, A.J.

remained with his father and stepmother. Schwarz said she did all she

could within the system to try to remove her son from their home. But

HRS brushed all the complaints aside, she said.

"Barbara Black was supposed to have investigated the calls, but

she just kept brushing them off," Schwarz said. Schwarz said she

"felt furious and helpless" when she saw a report signed by

Black stating that reports of abuse of A.J. were unfounded and instigated

by her.

"I want everybody responsible to pay for what they've done,"

Schwarz said.

Although Lambrecht would not comment on Black's indictment, she did

say that HRS officials cannot argue with many of the grand jury's findings.

"I sincerely believe our workers do the best they can with what

we've got," Lambrecht said.

In its report, the grand jury said A.J.'s death may have been avoided

if procedures had been followed and evidence acted on.

"Andrew J. Schwarz's files had enough information in them to strongly

suggest removing him from the home. There appeared to be an overwhelming

drive by [HRS) to keep Andrew J. Schwarz with his natural father even

when the Child Protection Team, staff meetings and other documented

information showed this was not in his best interest," the grand

jury report said.

The grand jury also cited a lack of follow-up and communication between

HRS workers and police in Broward and Palm Beach counties.

Back To Top